Summary Card

Overview

Congenital haemangiomas are rare vascular tumors present at birth that resemble, but are distinct from, infantile haemangiomas.

Clinical Presentation

Congenital haemangiomas (CHs) are fully formed at birth and present as solitary vascular lesions. They are classified into three types: RICH, PICH, and NICH, based on their involution behaviour and clinical features.

Involution

RICHs involute rapidly, starting from 1 month and resolving by 1 year; PICHs show partial involution and stabilize by 12 months. Involution patterns help differentiate subtypes.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is clinical, but ultrasound & MRI are used as adjuncts for imaging. Clinical presentation, histology, and immunohistochemistry (IHC) are important for differentiating CH from IH.

Management

Observation is first-line for most congenital haemangiomas. Surgery is reserved for complications or persistent lesions. Lasers may address residual telangiectasia.

Complications

Early complications include ulceration, haemorrhage, thrombocytopenia, and high-output cardiac failure. Late complications include pain, thrombosis, and tissue necrosis.

Primary Contributor: Dr Waruguru Wanjau, Educational Fellow

Verified by thePlasticsFella ✅

Overview of Congenital Haemangioma

Congenital haemangiomas are rare vascular tumors present at birth that resemble, but are distinct from, infantile haemangiomas.

Congenital haemangiomas are rare vascular tumors that are fully developed at birth. Although they can resemble infantile haemangiomas, congenital haemangiomas (CHs) are a separate entity with distinct biological and clinical features. Their diagnosis and management depend on recognizing these differences early.

- Fully Formed at Birth: CHs are present and mature at delivery, unlike infantile haemangiomas which appear postnatally and proliferate.

- GLUT1-Negative: This immunohistochemical marker is absent in CHs, helping distinguish them from other vascular lesions (Atheron, 2022).

- Do Not Grow After Birth: CHs do not undergo postnatal proliferation and instead follow one of three involution patterns (Braun, 2020).

- RICH: Rapidly involuting.

- PICH: Partially involuting.

- NICH: Non-involuting.

- Uncommon and Poorly Understood: Their exact pathophysiology remains unclear, and they are significantly rarer than infantile haemangiomas.

- Male Predominance: Observed more frequently in males, with a reported sex ratio of around 1.7:1.

A congenital haemangioma of the lower limb is illustrated below.

Rarely, some NICHs can show tardive expansion (postnatal growth), which may represent a separate CH subtype under ongoing investigation (Braun, 2020).

Clinical Presentation of Congenital Haemangioma

Congenital haemangiomas (CHs) are fully formed at birth and present as solitary vascular lesions. They are classified into three types: RICH, PICH, and NICH, based on their involution behaviour and clinical features.

CHs are rare vascular tumours that resemble infantile haemangiomas but are fully developed at birth and follow distinct clinical courses. They present as solitary, well-demarcated lesions (red-purple) with telangiectasia and often a pale peripheral halo (Braun, 2020).

General Features

- Location: Most CHs occur on the extremities, followed by the head and neck, then the trunk (Enjolras, 2006).

- RICHs: On the head and neck or extremities (Atheron, 2022).

- PICHs: On the head and neck, trunk, and extremities,

- NICHs: Typically found on the trunk and extremities.

- Size: Most are >2 cm; around one-third, especially NICHs, exceed 5 cm (Braun, 2020).

- Shape & Number: Typically solitary lesions with a discoid or plaque-like appearance.

- Halo: More than 50% show peripheral vasoconstrictive halos.

Features by Subtype

Congenital haemangiomas are classified based on their natural history and clinical behaviour. While RICH, PICH, and NICH show distinct outcomes, overlapping features suggest these variants exist along a pathological continuum (Braun, 2020).

Rapidly Involuting Congenital Haemangioma (RICH)

- At Birth: Appears as a bulky, exophytic mass, resembling a raised tumour (Braun, 2020; Atherton, 2022).

- Begins involution within the first month of life and typically completes by 1 year.

- May be associated with transient thrombocytopenia due to localised intravascular consumptive coagulopathy.

- Primarily found on the head, neck, and extremities (Atherton, 2022).

- Cannot be reliably distinguished from PICH at birth, only two-thirds undergo complete involution (Braun, 2020).

Partially Involuting Congenital Haemangioma (PICH)

- Clinically Resembles RICH at Birth: bulky, red to violaceous patches, plaques, or masses with telangiectasia and surrounding pallor (Atherton, 2022).

- Undergoes partial involution, then stabilises in size (Nasseri, 2014).

- May exhibit subcutaneous draining channels and develop central ulceration, which is more common in PICH and may predict incomplete involution (Braun, 2020).

- Can cause neuropathic pain, likely due to intralesional nerve bundles (Braun, 2020).

- Often stabilises at a median age of 12 months (Braun, 2020).

- Found on the head, neck, trunk, and extremities.

Non-Involuting Congenital Haemangioma (NICH)

- At Birth: Appears as a flat, solitary plaque.

- Lesions are pink to violaceous with coarse telangiectasia, bluish discolouration, and a blanching peripheral halo (Atherton, 2022).

- Does not regress; may grow proportionately with the child.

- May present with delayed-onset neuropathic pain due to nerve dystrophy (Braun, 2020).

- Typically located on the trunk and extremities.

- May result from in utero involution of RICH (Enjolras, 2006).

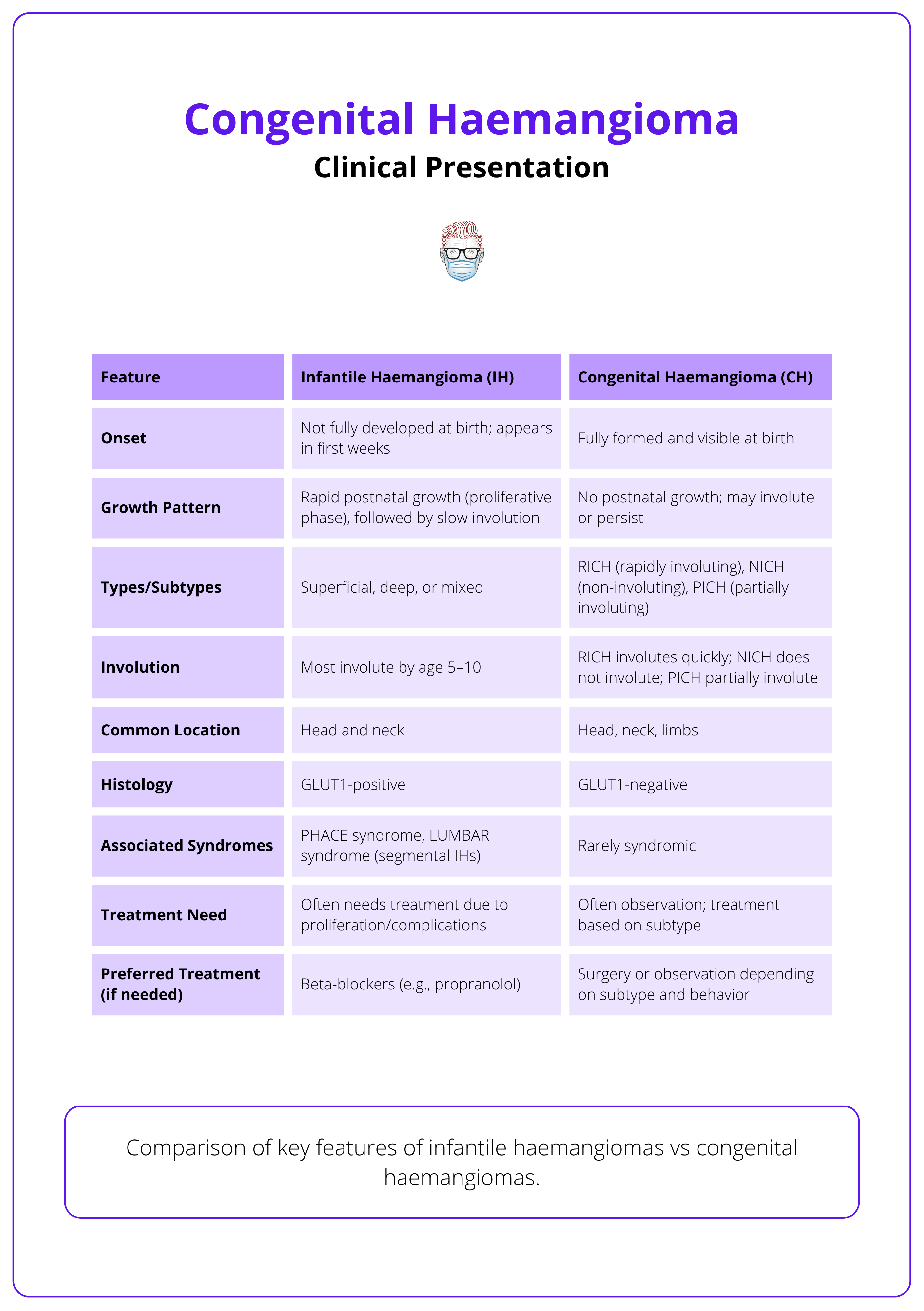

Infantile vs Congenital Haemangioma

IH and CH are both vascular tumours but have distinct features in their presentation, course of involution, and treatment approaches. Below is a comparison of key features of infantile haemangiomas vs congenital haemangiomas.

Involution of Congenital Haemangioma

RICHs involute rapidly, starting from 1 month and resolving by 1 year; PICHs show partial involution and stabilize by 12 months. Involution patterns help differentiate subtypes.

The timing and pattern of involution are central to distinguishing congenital haemangioma subtypes. One-third of CHs that appeared RICH at birth undergo incomplete involution to become PICHs (Braun, 2020).

- RICH

- Involution begins at a median age of 4 weeks.

- Lesions completely regress by a median age of 13 months.

- One-third of CHs that appear as RICH at birth ultimately undergo only partial involution.

- PICH

- Involution begins around 7 weeks.

- Lesions stabilize at a median of 12 months without complete regression.

- Often evolve from lesions initially resembling RICH.

Diagnosis of Congenital Haemangiomas

The main modality of diagnosis is clinical, but ultrasound and MRI can be used as adjuncts for imaging. Clinical presentation, histology, and immunohistochemistry (IHC) are important for differentiating CH from IH.

Congenital haemangiomas (CHs) are usually diagnosed based on clinical presentation. However, when features are atypical, biopsy and imaging are essential to rule out other vascular tumours such as kaposiform haemangioendothelioma or tufted angioma (Putra, 2017).

The imaging and histological data of the three CH subtypes are rather similar (Braun, 2020). Adjuncts to clinical diagnosis are imaging and echocardiography & coagulation studies.

Imaging

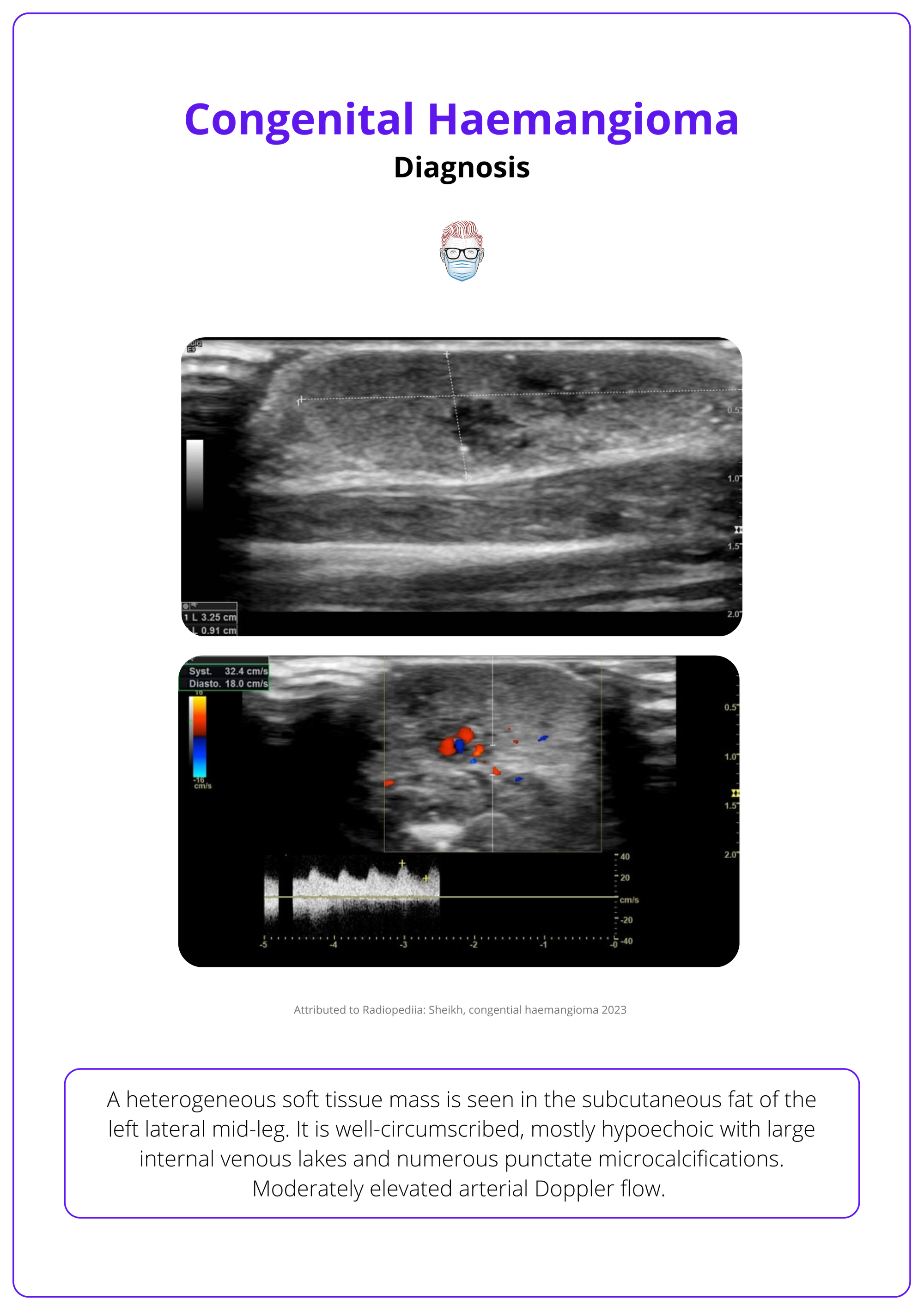

Ultrasound

CHs are well-circumscribed, highly vascularised tumours with enlarged arteries and veins, and high-velocity flow (Nasseri, 2014).

- Hypoechoic, homogeneous, or heterogeneous.

- Calcifications may appear (seen in 2 RICHs and 1 PICH).

- Microshunts are more frequent in NICH.

An ultrasound of a congenital haemangioma is illustrated below.

MRI

- T1-weighted: Well-defined, homogeneous lesions with gadolinium enhancement (Braun, 2020).

- T2-weighted: Hyperintense, patchy or homogeneous signals with flow voids and fat stranding (Nasseri, 2014).

Echocardiography & Coagulation Studies

Used in large CHs to assess high-output cardiac states and thrombocytopenia (Hinen, 2020).

Histopathology

- CHs consist of capillary lobules with draining arteries and normal or dysplastic veins in fibrous stroma (El Zein, 2020).

- Arteriovenous fistulae may be seen.

- Epidermis is atrophic with loss of dermal appendages (Atherton, 2022).

Immunohistochemistry

- GLUT-1 Negative: Unlike infantile haemangiomas.

- PS100 Positive: Identifies variable intralesional nerve bundles and nerve hypertrophy.

Distinguishing CH from IH

- CH is present at birth, IH appears postnatally.

- CH is GLUT-1 negative, IH is GLUT-1 positive.

- CH may show heterogeneous imaging, thrombi, aneurysms, or ill-defined margins (Sheikh, 2023).

Management of Congenital Haemangiomas

Observation is first-line for most congenital haemangiomas. Surgery is reserved for complications or persistent lesions. Lasers may address residual telangiectasia.

Observation is the mainstay of treatment for most congenital haemangiomas (CHs), as many regress spontaneously without intervention (Atherton, 2022). When treatment is considered, options include surgery and laser therapy.

Indications for Surgery

Surgical excision (with or without preoperative embolisation) may be required in specific clinical situations,

- Life-threatening haemorrhage or hemodynamic instability.

- Significant arteriovenous shunting causing heart failure, anaemia, or thrombocytopenia (Braun, 2020; Atherton, 2022; Sheikh, 2023).

- Liver CHs with high-output cardiac failure (Hinen, 2020).

- Persistent or severe ulceration (Atherton, 2022).

- Cosmetic or functional impairment.

- Residual atrophic tissue following partial involution (Braun, 2020).

Laser Therapy

Pulsed dye laser may be used to treat associated telangiectasias (Hinen, 2020).

Unlike infantile haemangiomas, CHs do not respond to propranolol. Medical therapy is generally ineffective (Sheikh, 2023).

Complications of Congenital Haemangiomas

Early complications include ulceration, haemorrhage, thrombocytopenia, and high-output cardiac failure. Late complications include pain, thrombosis, and tissue necrosis.

Congenital haemangiomas (CHs) may result in both local and systemic complications depending on lesion size, location, and vascular dynamics.

Early Complications

- Ulceration: Most frequently associated with PICH; also a predictor of partial involution.

- Haemorrhage: Particularly in large CHs (Atherton, 2022).

- Thrombocytopenia: Transient, mild to moderate; associated with RICH due to localized intravascular consumptive coagulopathy (Atherton, 2022).

- High-Output Cardiac Failure: Seen in large, highly vascular CHs; typically transient and resolves after involution.

Late Complications

- Neuropathic Pain: Seen in NICH; may result from intralesional nerve dystrophy (Braun, 2020).

- Superficial Thrombosis: Involves vessels close to the lesion surface.

- Tissue Necrosis: Due to compromised perfusion of overlying skin.

Thrombocytopenia in RICH and NICH is usually transient and should not be confused with Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon, which requires a different clinical approach (Braun, 2020).

Conclusion

1. Overview: Congenital haemangiomas (CHs) are rare, benign vascular tumors, fully developed at birth. They are GLUT1-negative and present in three clinical types: RICH, PICH, and NICH, based on their involution behaviour.

2. Clinical Presentation: CHs are solitary, red-to-violaceous lesions with telangiectasia and often a pale halo. RICH involutes rapidly, PICH partially regresses, and NICH remains stable or grows proportionately. Lesions commonly occur on the extremities, head, neck, or trunk.

3. Diagnosis and Involution: Diagnosis is primarily clinical, supported by imaging (ultrasound, MRI) and histopathology. Involution patterns differ: RICH resolves by 1 year, PICH stabilizes by 12 months, and NICH persists. CHs are GLUT1-negative, distinguishing them from infantile haemangiomas.

4. Treatment and Complications: Most CHs are managed conservatively. Surgery is reserved for complications like bleeding, ulceration, or cardiac issues. Laser therapy may improve residual telangiectasia. Complications include ulceration, haemorrhage, pain, and high-output cardiac failure in large lesions.

Further Reading

- Atherton K, Hinen H. Vascular Anomalies: Other Vascular Tumors. Dermatol Clin. 2022 Oct;40(4):401-423. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2022.06.011. Epub 2022 Sep 16. PMID: 36243428.

- North PE, Waner M, James CA, Mizeracki A, Frieden IJ, Mihm MC Jr. Congenital nonprogressive hemangioma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity unlike infantile hemangioma. Arch Dermatol. 2001 Dec;137(12):1607-20. doi: 10.1001/archderm.137.12.1607. PMID: 11735711.

- Nasseri E, Piram M, McCuaig CC, Kokta V, Dubois J, Powell J. Partially involuting congenital hemangiomas: a report of 8 cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Jan;70(1):75-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.018. Epub 2013 Oct 29. PMID: 24176519.

- Braun V, Prey S, Gurioli C, Boralevi F, Taieb A, Grenier N, Loot M, Jullie ML, Léauté-Labrèze C. Congenital haemangiomas: a single-centre retrospective review. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2020 Dec 7;4(1):e000816. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000816. PMID: 33324762; PMCID: PMC7722829.

- Enjolras O, Picard A, Soupre V. Hémangiomes congénitaux et autre tumeurs vasculaires infantiles rares [Congenital haemangiomas and other rare infantile vascular tumours]. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2006 Aug-Oct;51(4-5):339-46. French. doi: 10.1016/j.anplas.2006.07.006. Epub 2006 Sep 25. PMID: 16997442.

- Sheikh Z, Weerakkody Y, Ashraf A, et al. Congenital haemangioma. Reference article, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 08 May 2025).

- Putra J, Gupta A. Kaposiform haemangioendothelioma: a review with emphasis on histological differential diagnosis. Pathology. 2017 Jun;49(4):356-362. doi: 10.1016/j.pathol.2017.03.001. Epub 2017 Apr 21. PMID: 28438388.

- .El Zein S, Boccara O, Soupre V, Vieira AF, Bodemer C, Coulomb A, Wassef M, Fraitag S. The histopathology of congenital haemangioma and its clinical correlations: a long-term follow-up study of 55 cases. Histopathology. 2020 Aug;77(2):275-283. doi: 10.1111/his.14114. Epub 2020 Jul 26. PMID: 32281140.

- Hinen HB, Trenor CC 3rd, Wine Lee L. Childhood Vascular Tumors. Front Pediatr. 2020 Oct 22;8:573023. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.573023. Erratum in: Front Pediatr. 2021 Feb 24;9:649610. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.649610. PMID: 33194900; PMCID: PMC7642460.

- The Plastics Fella. Infantile Hemangiomas. November 2024. Accessed on 7th May 2025.