Summary Card

Overview

Compartment syndrome of the hand is a rare but urgent surgical condition caused by increased pressure within osseofascial compartments, leading to neurovascular compromise.

Pathogenesis

The aetiology of this syndrome centres on raised intracompartmental pressure caused by increased contents or decreased space. Both traumatic and non-traumatic mechanisms may trigger this process.

Clinical Assessment

Compartment syndrome of the hand is primarily a clinical diagnosis. The earliest and most reliable sign is pain out of proportion, especially on passive stretch.

Investigations

Compartment syndrome is primarily a clinical diagnosis. Pressure monitoring and other tests may support the diagnosis, but should never delay intervention if suspicion is high.

Management

Management hinges on early recognition, immediate decompression, and careful post-operative care. Delays can result in permanent disability or limb loss.

Outcomes

Early fasciotomy, ideally within 6 hours, offers the best chance of preserving function. Postoperative wound care, early mobilisation, and structured rehabilitation are essential to maximise recovery.

Updated by: Dr Hatan Mortada, Educational Fellow

Verified by thePlasticsFella ✅

Overview of Compartment Syndrome of the Hand

Compartment syndrome of the hand is a time-sensitive condition caused by elevated pressure within fascial compartments, leading to vascular and nerve compromise.

Compartment syndrome of the hand is defined as elevated pressure within a closed osseofascial space, resulting in impaired microcirculation.

This occurs when the pressure within one or more of the hand’s ten osseofascial compartments exceeds capillary perfusion pressure, impairing blood flow to muscles and nerves.

This can rapidly progress to ischemia, necrosis, and permanent functional loss if not promptly addressed.

Although more common in the leg and forearm, the hand remains a high-risk site due to,

- Dense compartmental anatomy.

- Delicate vascular supply required for fine motor function.

Most cases are associated with trauma, but non-traumatic causes, including infections, vascular events, and tight dressings.

Compartment syndrome of the hand may result from,

- Increased contents (e.g., bleeding, swelling, infection).

- Decreased space (e.g., tight dressings, external compression).

The resulting vascular compromise can cause,

- Tissue hypoxia.

- Muscle and nerve ischemia.

- Irreversible necrosis if not treated urgently.

Progression from reversible ischemia to irreversible necrosis may occur within 6 to 8 hours (Hargens, 1998).

Epidemiology

Incidence

Demographics

- Most common in males under 35, likely due to larger muscle mass and higher trauma exposure (McQueen, 2000).

Most Common Causes

- Fractures (especially distal radius and ulna)

- Crush injuries

- Burns

- High-pressure injection injuries

Anatomical Sites

- While the leg remains the most common location, the hand, forearm, and foot are also recognized as high-risk sites.

Irreversible muscle and nerve damage can occur in as little as 6 hours; always escalate promptly. Do not delay surgical referral while waiting for investigations.

Pathogenesis of Hand Compartment Syndrome

Compartment syndrome of the hand is caused by raised intracompartmental pressure, whether from increased contents or reduced space, leading to vascular compromise and tissue ischemia.

Compartment syndrome of the hand can arise from traumatic or non-traumatic mechanisms. Regardless of the trigger, the underlying process is the same: elevated pressure within a closed fascial compartment impairs microvascular flow, threatening tissue viability (Hargens, 1998).

Causes

Compartment syndrome of the hand may arise from traumatic or non-traumatic mechanisms.

Traumatic Causes

Trauma is the most common cause, including,

- Fractures

- Distal radius and ulna fractures.

- Carpometacarpal dislocations.

- Paediatric supracondylar fractures of the humerus (Especially in the pediatric population).

- Crush Injuries: Prolonged compression or high-energy blunt trauma.

- Burns: Circumferential thermal or electrical burns cause skin tightening and swelling.

- High-Pressure Injection Injuries: Paint, grease, or air injected into tissues under pressure.

- Vascular Injuries: Associated with revascularisation procedures or trauma (especially with reperfusion injuries).

Non-Traumatic Causes

Less common but clinically important.

- Infections: Abscess formation, necrotising fasciitis.

- Reperfusion Injury: Post-ischemic swelling following vascular repair.

- Seizure-Induced Muscle Overuse: Prolonged muscle contractions during seizures.

- Constrictive Dressings or Splints: Tight casts or bandages causing external compression.

- Drug Overdose or Prolonged Immobilisation: Unconscious patients in one position for prolonged periods.

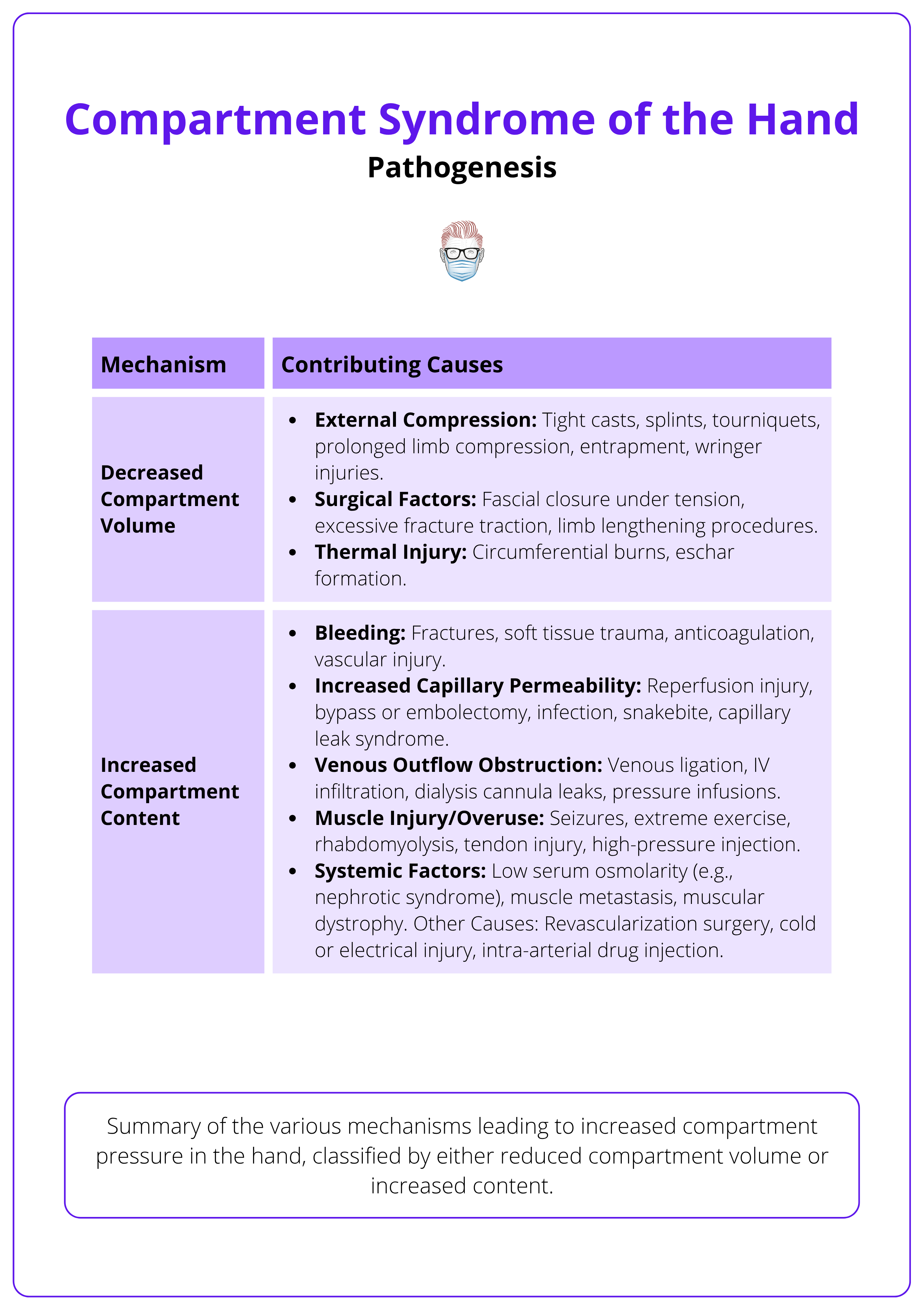

The mechanisms leading to hand compartment syndrome are summarised below.

Pathophysiology

Compartment syndrome develops when raised interstitial pressure compromises capillary perfusion, initiating a cycle of ischemia, tissue damage, and escalating pressure.

Compartment syndrome arises when intracompartmental pressure increases to a level that exceeds capillary perfusion pressure, impeding oxygen and nutrient delivery to tissues. This results in progressive ischemia, particularly affecting muscles and nerves.

Pathological Process

- Interstitial pressure rises due to either internal swelling (e.g., bleeding, edema) or external compression (e.g., tight casts).

- Once capillary perfusion pressure is exceeded, oxygen delivery falls.

- Tissue hypoxia triggers cellular swelling, acidosis, and metabolic failure.

- A positive feedback loop ensues: ischemia → cell damage → more edema → rising pressure.

- If untreated, this leads to irreversible necrosis of nerves and muscles.

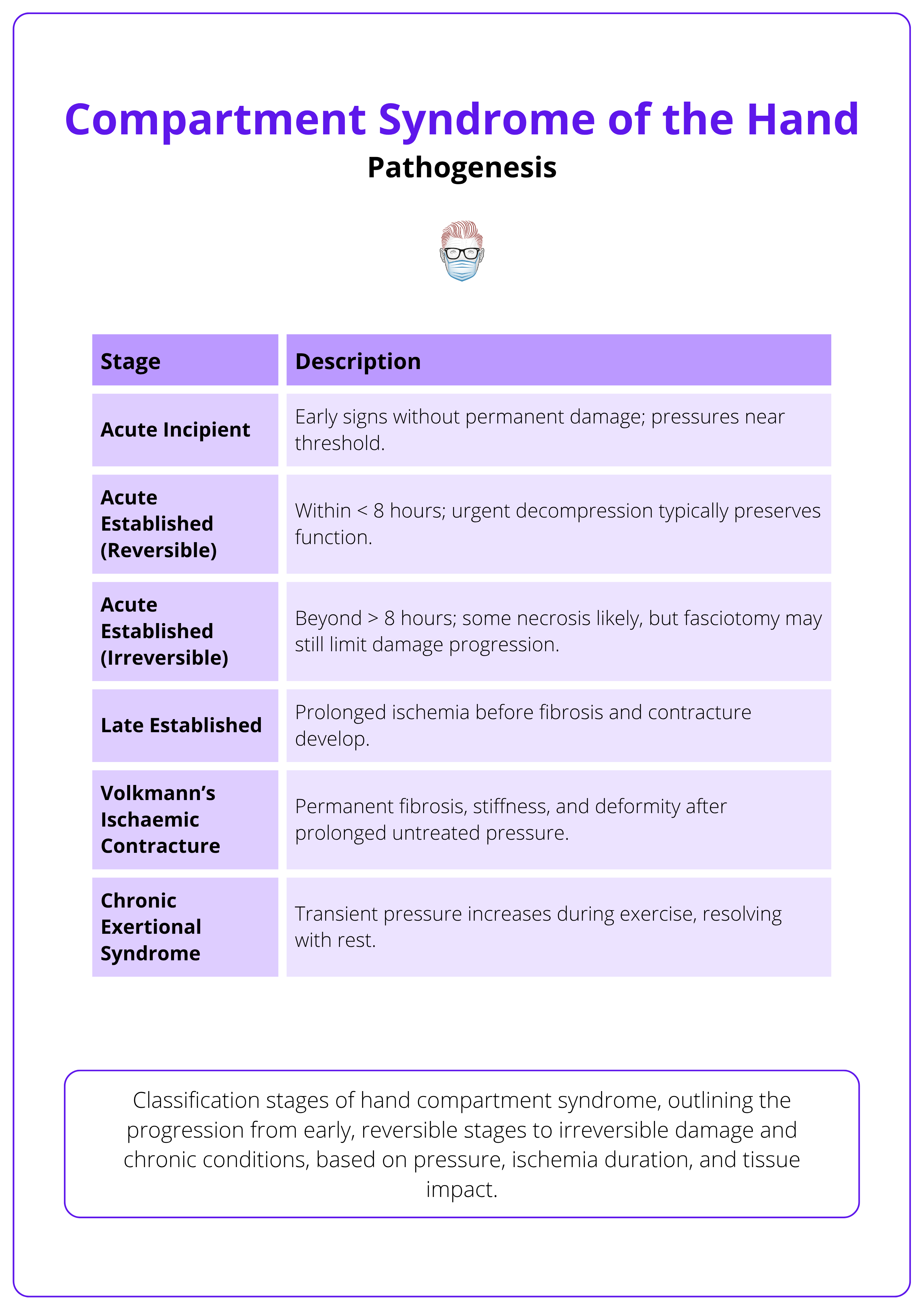

The stages of progression are summarised below.

Consequences of Unrelieved Pressure

- Venous Congestion: Impairs outflow and worsens swelling.

- Arterial Inflow Restriction: Worsens ischemia.

- Neuromuscular Damage: Ischemic injury to nerves and muscles.

- Fibrosis and Contractures: e.g., Volkmann’s contracture from chronic ischemic damage.

Always remove constrictive dressings or casts in suspected cases. This may reverse early ischemia and prevent surgery.

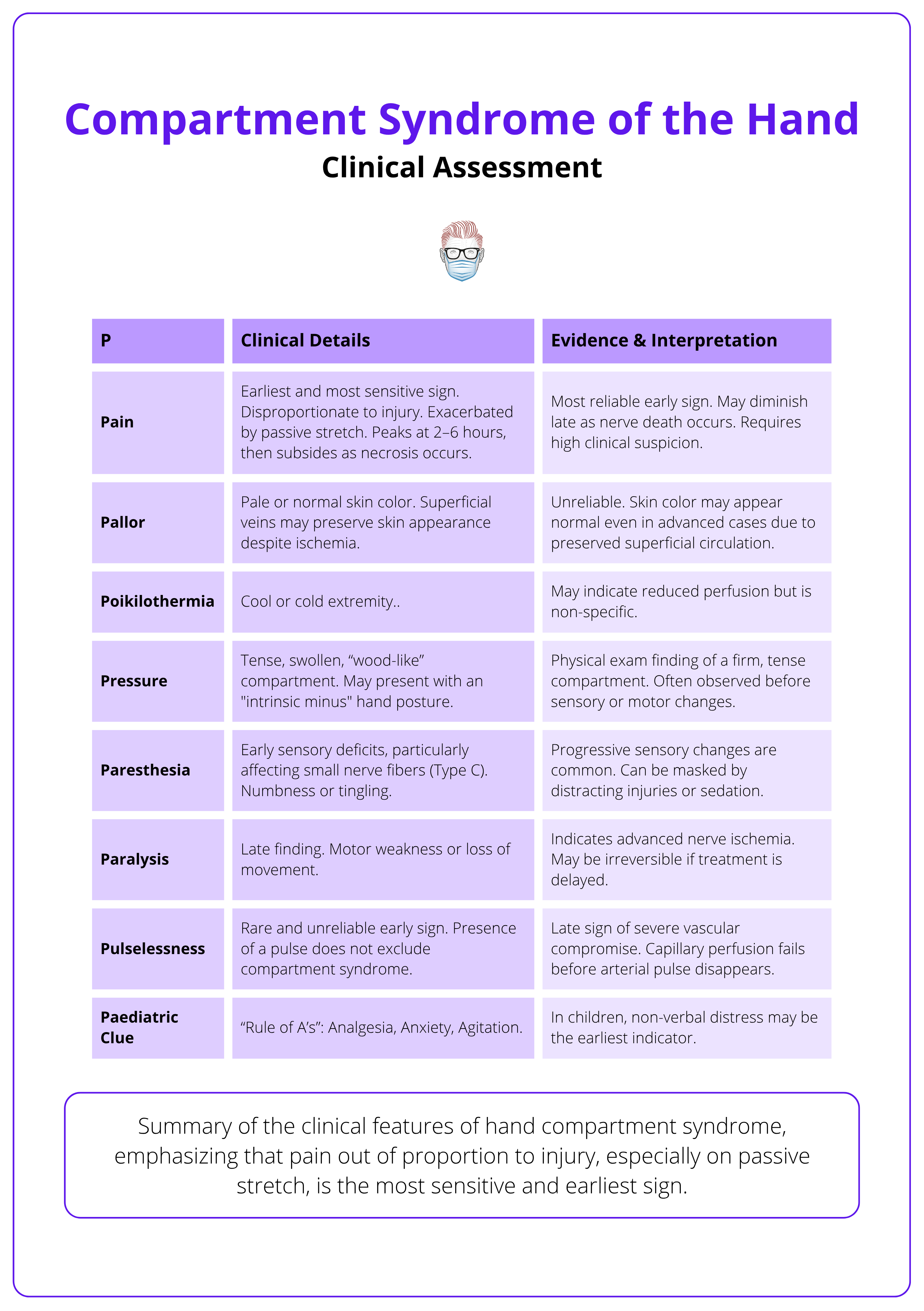

Clinical Assessment of Hand Compartment Syndrome

Compartment syndrome of the hand is primarily a clinical diagnosis. The earliest and most reliable sign is pain out of proportion, especially on passive stretch.

A thorough clinical assessment is essential, especially because delay in diagnosis can lead to irreversible damage. The syndrome can develop within hours, so high clinical suspicion is vital.

History

- Mechanism of Injury: Fractures, crush injuries, burns, high-pressure injection.

- Timing: Onset usually within 6-48 hours (Whitesides, 1996).

- Symptoms

- Severe, escalating, and disproportionate pain.

- Pain worsened by passive stretch.

- Deep ache, burning, or tightness.

- Numbness or tingling (paraesthesia).

- The Rule of A’s (Paediatric Red Flags): These may indicate pain out of proportion in non-verbal or young children.

- Analgesia requirement.

- Anxiety.

- Agitation.

Physical Examination

Early Clinical Signs

- Pain with passive stretch (Leversedge, 2011).

- Tense, swollen compartments (wood-like feel).

- Intrinsic minus hand posture.

Progressive or Late Signs

- Paraesthesia.

- Motor weakness or paralysis.

- Pallor and pulselessness (very late and unreliable).

These clinical signs and diagnostic features are summarised below.

Risk Factors

- Unresponsive or sedated patients.

- Children with limited communication.

- Polytrauma patients.

- Patients after vascular repair.

- Tight splints, dressings, or casts.

- Coagulopathies or bleeding disorders.

- Prolonged immobilisation (e.g., drug overdose).

Differential Diagnosis

- Severe crush injury without compartment syndrome.

- Cellulitis or deep abscess.

- Peripheral nerve compression.

- Arterial or venous occlusion.

- Rhabdomyolysis without compartment syndrome.

Do not rely on the presence of pulses to exclude compartment syndrome — capillary perfusion fails before arterial flow ceases.

Investigations for Hand Compartment Syndrome

Compartment syndrome is primarily a clinical diagnosis. Pressure monitoring and other tests may support the diagnosis, but should never delay intervention if suspicion is high.

In cases where the diagnosis is uncertain, such as in sedated or unresponsive patients, objective measurements can provide valuable guidance. However, clinical judgement remains paramount.

Clinical Diagnosis

The diagnosis of compartment syndrome is clinical and should be based on,

- History of at-risk injury (e.g., fracture, crush, burn, vascular repair).

- Classic clinical signs.

- Severe pain out of proportion.

- Pain on passive stretch.

- Tense swelling of the hand.

Sole reliance on pulses or skin color is misleading, as these may remain normal until late stages.

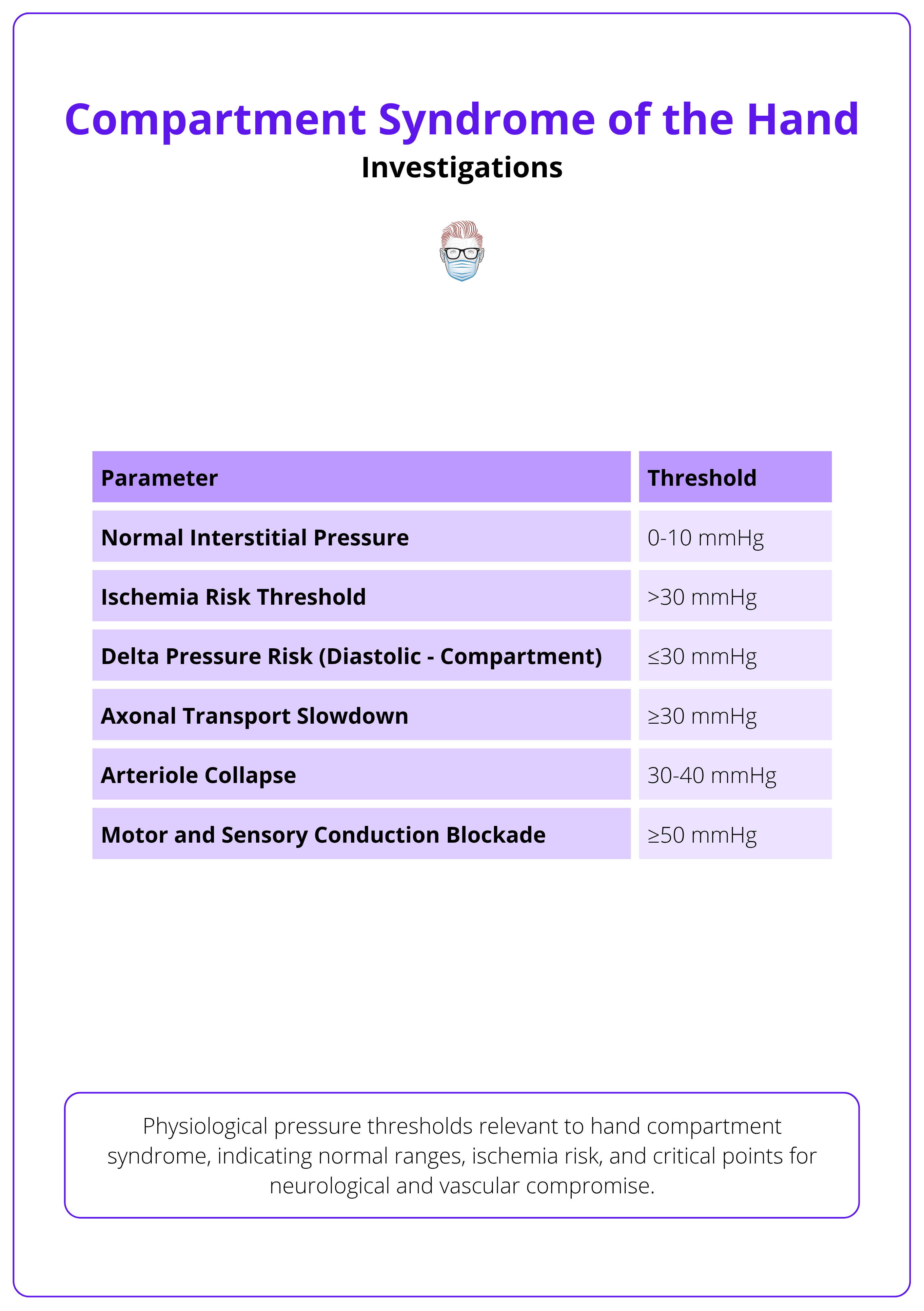

Physiological Pressure Thresholds

- Normal Pressure: 0–10 mmHg.

- Ischemic Threshold: >30 mmHg.

- Critical Delta Pressure: ≤30 mmHg (Whitesides, 1996). (Delta pressure = Diastolic BP − Compartment pressure).

Key pressure parameters and their clinical implications are summarised below.

Compartment Pressure Monitoring

When to measure,

- Unresponsive or sedated patients.

- Polytrauma with unreliable exams.

- Equivocal clinical findings.

Diagnostic Thresholds

- Absolute pressure ≥30 mmHg (Leversedge, 2011).

- Delta pressure ≤30 mmHg (Diastolic BP – Compartment Pressure)

Techniques for Measurement

- Needle or Slit Catheter Manometry: Measures resistance to saline injection or continuous pressure.

- Arterial Line Transducer Systems: Allows continuous monitoring.

Adjunct Investigations

While not diagnostic, these can support case assessment.

- Imaging

- X-Rays: Identify fractures or foreign bodies.

- Ultrasound with Doppler: Evaluate for vascular occlusion or thrombosis.

- MRI / CT Angiography (rarely required): Assess vascular or soft tissue status in complex cases.

- Laboratory Tests

- Creatine Phosphokinase (CPK): Elevated in muscle damage or rhabdomyolysis.

- Renal Function Tests and Urinalysis: Check for myoglobinuria and kidney injury.

- Full Blood Count and Coagulation Panel: Pre-operative assessment, rule out bleeding disorders.

- MRI

- Evaluates soft tissue viability and degree of myonecrosis.

- Used post-operatively in selected cases for surgical planning or rehabilitation strategy (Leversedge, 2011).

The delta pressure is often more accurate than absolute pressure — especially useful in hypotensive patients.

Management of Hand Compartment Syndrome

Management hinges on early recognition, immediate decompression, and careful post-operative care. Delays can result in permanent disability or limb loss.

Compartment syndrome of the hand is a surgical emergency. Initial bedside measures can slow progression, but definitive treatment is urgent fasciotomy.

Initial (Non-Surgical) Management

While preparing for surgery, immediate bedside interventions can prevent worsening ischemia.

- Urgent surgical team consultation.

- Remove all constrictive dressings or splints.

- Keep the limb at heart level: Elevation too high may reduce arterial inflow.

- Monitor hemodynamics: Prevent hypotension with fluid resuscitation if needed.

- Repeat neurovascular assessments: Document changes every 30-60 minutes.

- Consider pressure monitoring if the patient is unresponsive or the diagnosis is unclear.

Systemic Monitoring

- Renal Function: Monitor for rhabdomyolysis-related kidney injury (check creatinine, urine myoglobin).

- Electrolytes: Correct imbalances to reduce risk of arrhythmias or muscle dysfunction.

- Coagulopathy Screening: Check coagulation panels in bleeding risk patients.

- Urinalysis: Detect myoglobinuria.

Surgical Management: Fasciotomy

Indications

- Clinical diagnosis of compartment syndrome.

- Compartment pressure ≥30 mmHg or Delta pressure ≤30 mmHg.

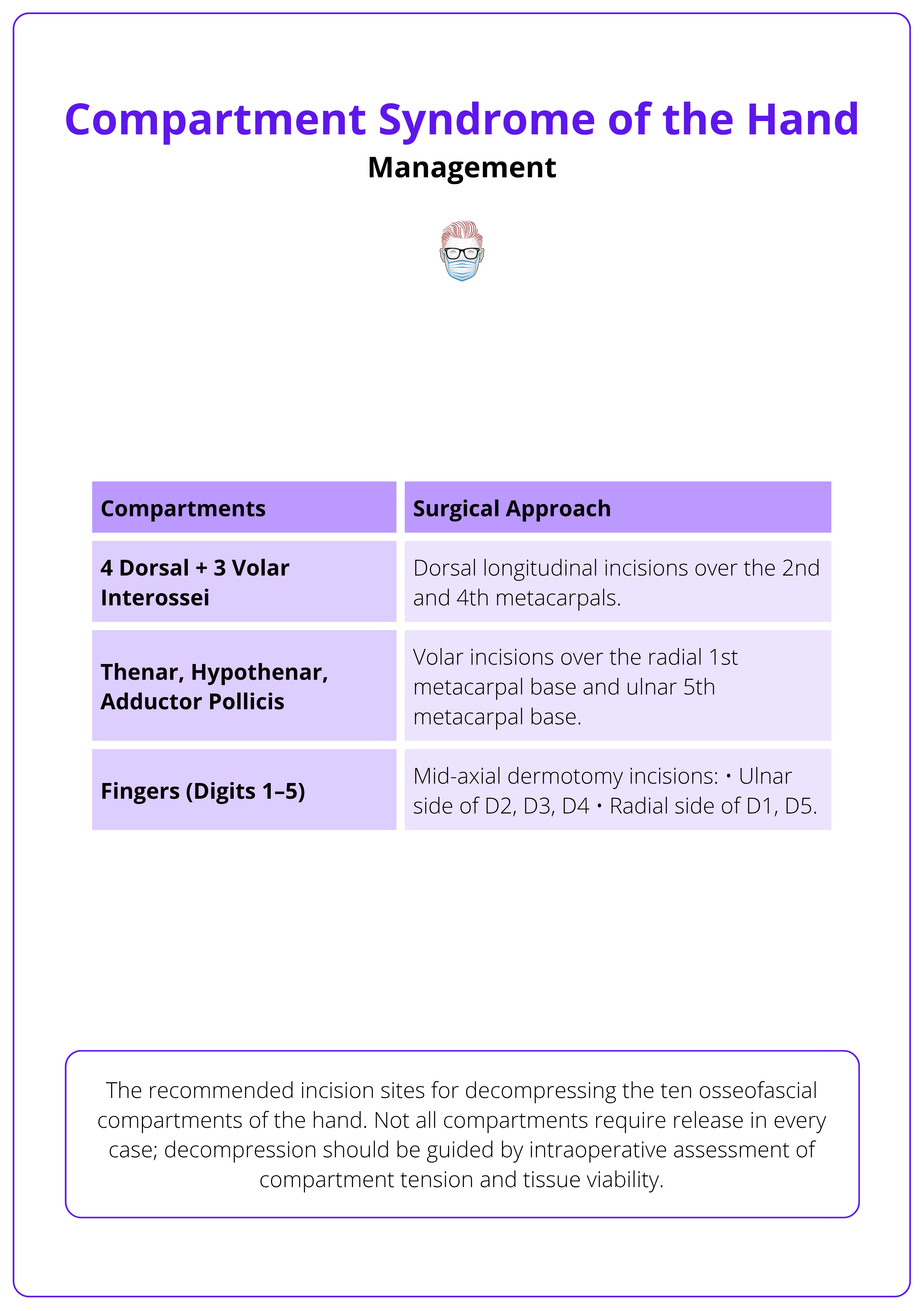

Surgical Anatomy and Compartments

The hand contains ten compartments.

- Thenar.

- Hypothenar.

- Adductor pollicis.

- Four dorsal interosseous.

- Three volar interosseous.

Releasing all compartments is not always necessary. Targeted release should be guided by intraoperative assessment.

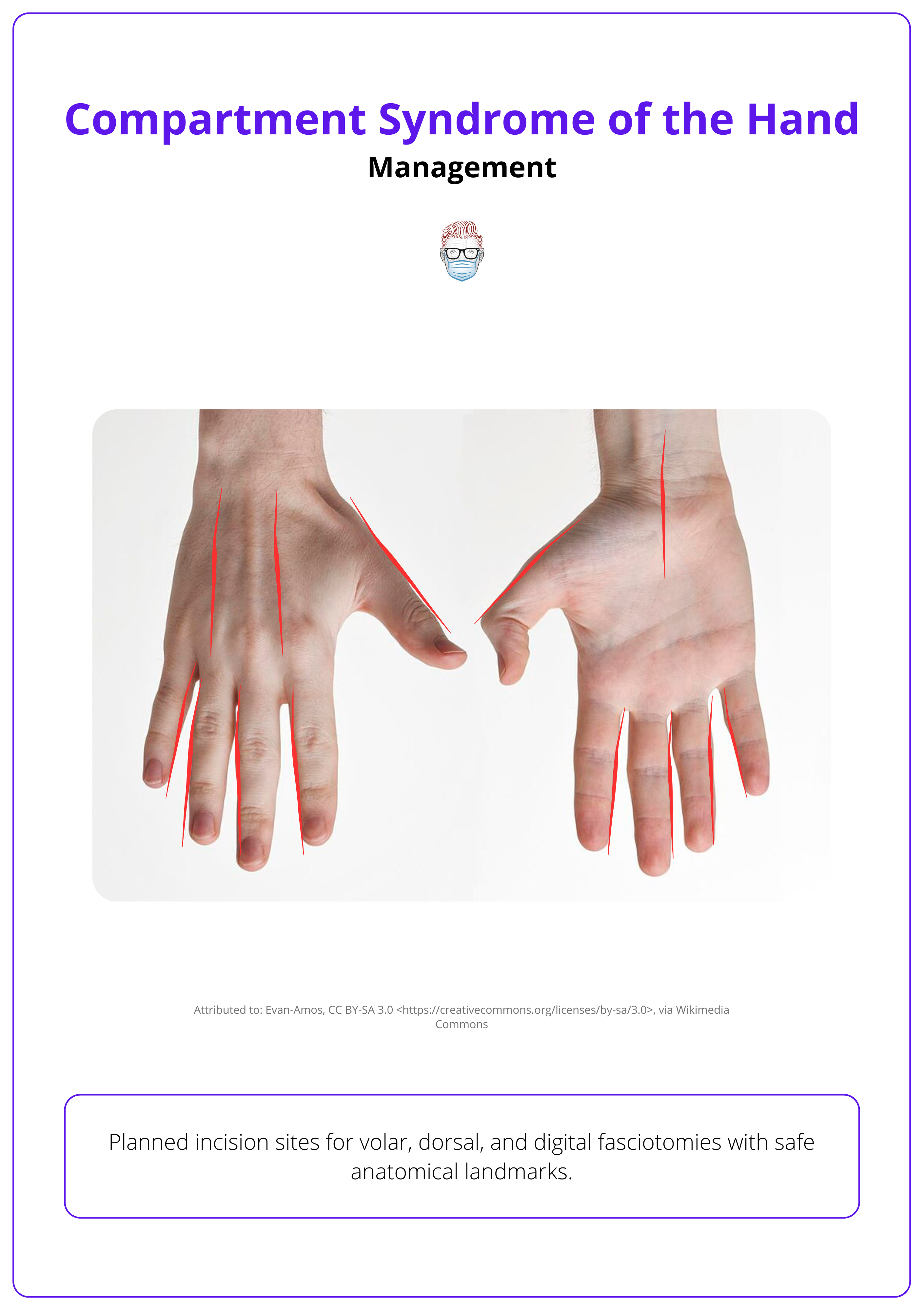

Surgical Techniques and Incisions

- Volar Incisions (Palmar)

- Extended Carpal Tunnel Incision: Releases the carpal tunnel, volar interossei, and adductor pollicis.

- Thenar Release: Longitudinal incision along the radial side of the thenar eminence.

- Hypothenar Release: Longitudinal incision along the ulnar border of the hand.

- Dorsal Incisions

- First Webspace Incision: Releases the adductor pollicis and first dorsal interosseous.

- Dorsal Metacarpal Incisions: Between the 2nd-3rd and 4th-5th metacarpals to release remaining dorsal interossei.

The surgical anatomy of hand compartments is summarised below.

- Digit Dermotomies

- Mid-axial incisions on tense, swollen fingers,

- Ulnar side of index/middle/ring.

- Radial side of thumb/little finger.

- Mid-axial incisions on tense, swollen fingers,

The surgical incisions are illustrated below.

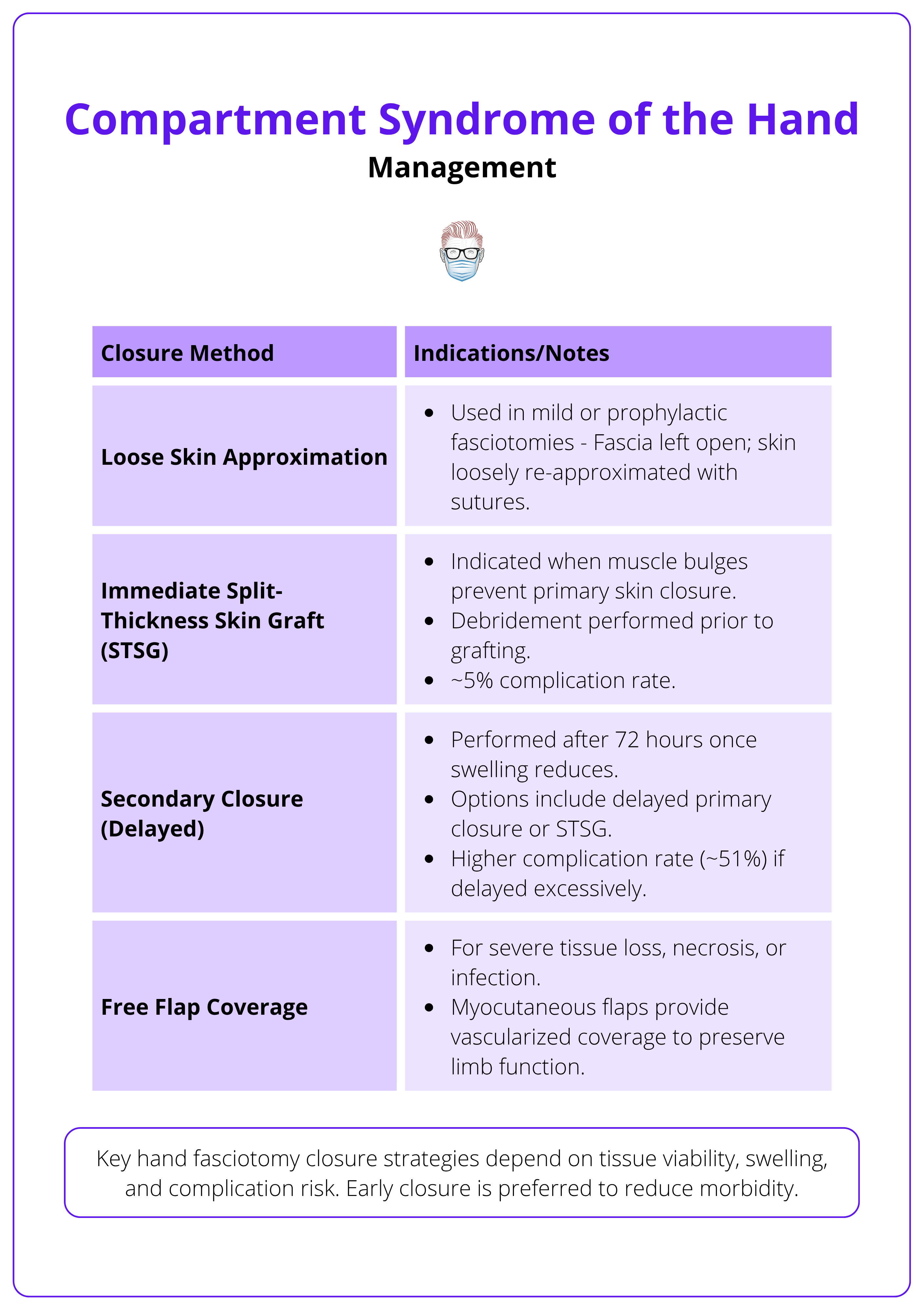

Post-Operative Care

Wound Management

- Leave wounds open with sterile dressings or negative-pressure wound therapy.

- Re-assess wounds at 24-48 hours for,

- Viability of tissues.

- Need for further debridement.

Intraoperative exposure of hand compartments is illustrated below.

Rehabilitation

- Elevate the limb and avoid constrictive dressings.

- Start early hand therapy to maintain the range of motion.

- Splint in functional position (wrist extended, MCPs flexed, IPs straight).

- Plan delayed closure or skin grafting once swelling resolves.

Closure strategies are summarised below.

Monitoring for Complications

- Infection.

- Rhabdomyolysis.

- Acute kidney injury.

- Delayed wound healing.

Not all ten compartments need to be released. Base your surgical plan on intraoperative findings and clinical assessment.

Outcomes of Hand Compartment Syndrome

Early fasciotomy, ideally within 6 hours, offers the best chance of preserving function. Postoperative wound care, early mobilisation, and structured rehabilitation are essential to maximise recovery.

Prognosis

Prognosis depends on timing of diagnosis and intervention.

- Fasciotomy within 6 hours: Nearly 100% limb function recovery.

- Fasciotomy after 6-12 hours: Two-thirds retain good function, some residual nerve damage expected.

- Fasciotomy after 36 hours: Poor outcomes, risk of non-salvageable tissue, infection, or amputation.

Functional Outcomes

If treated promptly,

- Full recovery of strength, sensation, and dexterity is possible.

- Return to daily activities and work without significant limitations.

If treated late or incompletely,

- Stiffness and weakness of the fingers or hand.

- Chronic pain and cold intolerance.

- Permanent sensory or motor deficits.

Long-term follow-up with hand therapy is crucial to maximise functional outcomes.

Common Complications

Complications may arise even with timely management. These include,

- Infection: Especially if necrotic tissue is present or closure is delayed.

- Rhabdomyolysis: Muscle breakdown leading to kidney injury.

- Contractures: Permanent flexion deformities of the fingers (Volkmann’s contracture).

- Nerve Damage: Persistent numbness or weakness.

- Wound Healing Issues: Delayed closure or need for skin grafting.

- Amputation: In cases of uncontrolled infection or tissue death.

- Chronic Pain or Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS).

Early rehabilitation after fasciotomy is essential to prevent stiffness, preserve function, and optimise recovery.

Post-Operative and Rehabilitation Care

Post-operative care is as important as the surgery itself. Careful wound management, early mobilisation, and a structured rehabilitation program are key to optimising long-term function.

Wound Care

After fasciotomy, wounds are left open to accommodate swelling and prevent further ischemia. Key steps include,

- Sterile, Non-Constrictive Dressings: Or negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT) to promote granulation tissue and manage exudate.

- Daily or 48-Hourly Wound Inspections: Look for signs of infection or tissue necrosis.

- Debridement of Non-Viable Tissue: Performed as needed based on wound assessment.

- Delayed Primary Closure: Once swelling reduces (typically 3–5 days post-op).

- Skin Grafting: May be required if primary closure is not possible.

Physical and Occupational Therapy

Rehabilitation goals,

- Prevent joint stiffness and tendon adhesions.

- Preserve range of motion.

- Strengthen muscles after recovery.

Key Interventions

- Splinting in a Functional Position: Wrist in extension, MCP joints flexed, IP joints extended.

- Early Passive and Active Mobilisation: Initiated once pain and swelling allow.

- Progressive Strengthening and Dexterity Exercises.

- Scar Management: Including massage, silicone therapy, and stretching.

Follow-up Considerations

- Monitor for late complications, including,

- Chronic Pain.

- Cold Intolerance.

- Nerve Dysfunction.

- Contractures.

- Functional Impairment.

- Psychosocial Support: For patients with amputation or persistent disability.

- Return-to-Work Assessments: Particularly for manual labourers.

Regular outpatient review with therapy updates ensures that any setbacks are identified early and managed proactively.

Negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT) not only manages swelling but can speed up the timing to definitive wound closure.

Conclusion

1. Overview: Compartment syndrome of the hand is a rare but time-sensitive surgical emergency. It results from raised pressure within the hand’s compartments, leading to vascular compromise, nerve ischemia, and potential tissue loss if untreated.

2. Aetiology: Compartment syndrome arises from trauma or non-traumatic factors that increase compartment contents or reduce compartment space.

3. Pathophysiology: Understanding the mechanical process by which increased pressure impairs venous outflow, collapses capillary perfusion, and triggers a positive feedback loop of tissue ischemia, progressing to irreversible necrosis if untreated.

4. Clinical Features: Early warning signs include pain out of proportion, pain on passive stretch, and tense compartments, while late signs include paralysis and pulselessness indicating severe or irreversible damage.

5. Diagnosis: The diagnosis is primarily clinical, supported by pressure monitoring (≥30 mmHg or delta ≤30 mmHg) when needed, and pulses and skin colour can remain deceptively normal until late.

6. Management: Initial management involves removing constrictive dressings, maintaining limb position, and monitoring for deterioration, while definitive treatment requires urgent fasciotomy using targeted incisions based on the hand’s compartmental anatomy.

7. Post-operative Care: Understanding the importance of wound management, early mobilisation, and structured rehabilitation, including hand therapy, splinting, and scar management.

8. Outcomes and Complications: You recognise that early intervention can achieve near-complete recovery, but delayed diagnosis increases the risk of infection, contracture, nerve damage, chronic pain, and amputation.

9. Follow-up and Multidisciplinary Care: You are prepared to coordinate long-term follow-up, involving occupational therapy, physical therapy, and psychosocial support, ensuring the best possible outcome.

Further Reading

- Matsen FA. Compartmental syndrome: a unified concept. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975;(113):8-14. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1192678

- Leversedge FJ, Moore TJ, Peterson BC, Seiler JG III. Compartment syndrome of the upper extremity. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(3):544-559. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.12.008

- Hargens AR, Mubarak SJ. Current concepts in the pathophysiology, evaluation, and diagnosis of compartment syndrome. Hand Clin. 1998;14(3):371-383. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9742417

- DiFelice A, Seiler JG III, Whitesides TE Jr. The compartments of the hand: an anatomic study. J Hand Surg Am. 1998;23(4):682-686. doi:10.1016/S0363-5023(98)80055-5

- Matava MJ, Whitesides TE Jr, Seiler JG III, Hewan-Lowe K, Hutton WC. Determination of the compartment pressure threshold of muscle ischemia in a canine model. J Trauma. 1994;37(1):50-58. doi:10.1097/00005373-199407000-00010

- McQueen MM, Gaston P, Court-Brown CM. Acute compartment syndrome. Who is at risk? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(2):200-203. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.82B2.9799

- Whitesides TE Jr, Heckman MM. Acute compartment syndrome: update on diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1996;4(4):209-218. doi:10.5435/00124635-199607000-00005

- Seiler JG III, Olvey SP. Compartment syndromes of the hand and forearm. J Am Soc Surg Hand. 2003;3(4):184-198. doi:10.1016/S1531-0914(03)00072-X

- Szabo RM, Gelberman RH. Peripheral nerve compression: etiology, critical pressure threshold, and clinical assessment. Orthopedics. 1984;7(9):1461-1466. doi:10.3928/0147-7447-19840901-11

- Mehta V, Chowdhary V, Lin C, Jbara M, Hanna S. Compartment syndrome of the hand: a case report and review of literature. Radiol Case Rep. 2018;13(1):212-215. doi:10.1016/j.radcr.2017.11.002