Summary Card

Overview

Lipomas are common benign tumours composed of mature fat cells. Though often asymptomatic and discovered incidentally, their clinical relevance lies in accurate diagnosis, exclusion of malignancy, and management of symptomatic or atypical lesions.

Aetiology

Lipomas arise from mature adipocytes and are usually idiopathic, though some are linked to trauma, genetics, or syndromic associations. Histologically, they are benign with several defined variants.

Clinical Presentation

Lipomas are often painless, soft, mobile swellings. Deeper or larger lesions may cause compression symptoms, and red flags such as rapid growth or deep location should raise suspicion for malignancy.

Imaging

Ultrasound is the first-line imaging modality for lipomas. MRI is the gold standard for deep or atypical lesions and helps distinguish lipomas from liposarcomas.

Management

Management of lipomas depends on their size, location, symptoms, and diagnostic certainty. While many can be observed, symptomatic or uncertain lesions may warrant excision.

Primary Contributor: Dr Kurt Lee Chircop, Educational Fellow

Verified by thePlasticsFella ✅

Overview of Lipoma

Lipomas are common benign tumours composed of mature fat cells. Though often asymptomatic and discovered incidentally, their clinical relevance lies in accurate diagnosis, exclusion of malignancy, and management of symptomatic or atypical lesions.

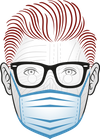

Lipomas are benign soft tissue tumours originating from mesenchymal tissue and composed of mature adipocytes. According to the WHO classification, they fall under the category of adipocytic soft tissue tumours, which includes several histologic variants with differing biological behaviours (Choi, 2021).

Lipomas have distinct histological variants based on cellular composition and location. These include,

- Angiolipoma: Painful; rich in capillaries; typically affects young adults.

- Spindle Cell Lipoma: Contains spindle cells; common in older men, especially on the posterior neck/back (Dabak, 2011).

- Myelolipoma: Adipose and hematopoietic tissue; usually found in the adrenal glands.

- Pleomorphic Lipoma: Features floret-like giant cells; may mimic sarcomas (Creytens, 2017).

- Fibrolipoma: Characterised by prominent fibrous tissue.

- Hibernoma: Rare; composed of brown fat; often intermuscular.

- Chondroid Lipoma: Contains cartilage-like matrix; can resemble sarcomas.

The image below shows two large lipomas on the back.

Lipoma variants differ in stromal elements, vascularity, and fibrous content; but all share an adipocytic origin (Choi, 2021).

Aetiology of Lipoma

Lipomas arise from mature adipocytes and are usually idiopathic, though some are linked to trauma, genetics, or syndromic associations. Histologically, they are benign with several defined variants.

Lipomas are benign mesenchymal tumours composed of mature adipocytes, typically surrounded by a thin fibrous capsule. Lipomas are commonly idiopathic (Marques, 1997), but several associated risk factors include,

- Genetic predisposition Familial multiple lipomatosis is an autosomal dominant condition where multiple lipomas develop (Lemaitre, 2021).

- Obesity: May increase visibility, but is not causative.

- Trauma: Blunt trauma is occasionally reported as a trigger, possibly through disruption of preadipocytes (Aust, 2007).

- Syndromes assoicated with lipomas include,

- Familial Multiple Lipomatosis: Autosomal dominant; multiple painless lipomas; no systemic features.

- Dercum’s Disease (Adiposis Dolorosa): Rare; painful lipomas; linked to obesity, fatigue, neuropsychiatric symptoms; middle-aged women.

- Roch-Leri Lipomatosis: Symmetric, painless subcutaneous lipomas; limbs and trunk; rare, non-inflammatory.

- Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba Syndrome: PTEN mutation; macrocephaly, intestinal hamartomas, multiple lipomas.

- Gardner’s Syndrome: FAP variant; cutaneous/subcutaneous lipomas, desmoid tumours, gastrointestinal polyps.

Lipomas are benign and distinct from liposarcomas, which are malignant and require different treatment strategies.

Clinical Presentation of Lipoma

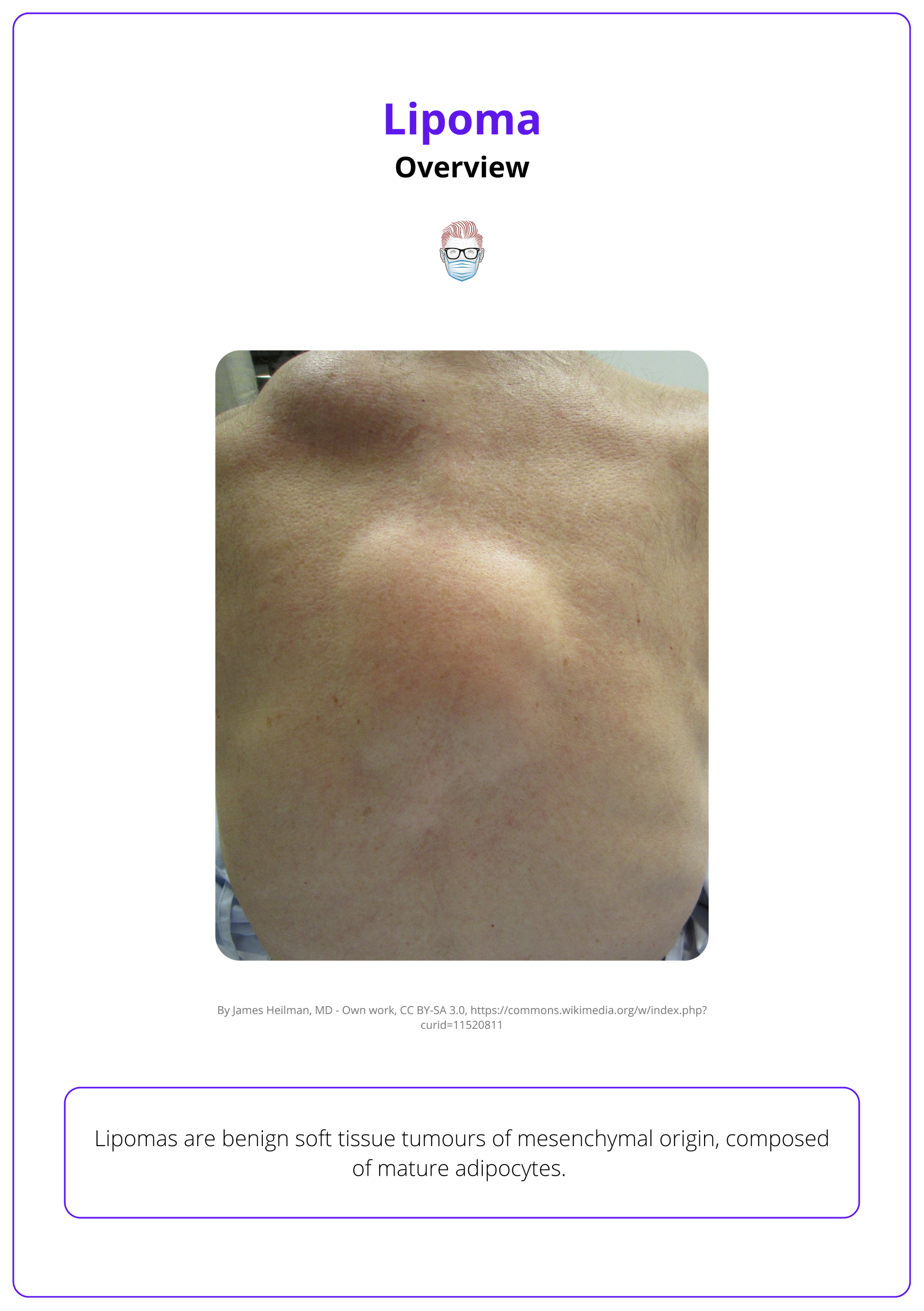

Lipomas are slow-growing, soft, mobile swellings. While usually asymptomatic, deeper or larger lesions can cause compressive symptoms. Features like rapid growth or deep location raise concern for malignancy.

History

Symptoms and Onset

- Typical Presentation: Gradually enlarging, painless mass.

- Pain: Uncommon, but may occur in angiolipomas, Dercum’s disease, or with nerve involvement.

- Functional Issues: Deep lesions may compress adjacent structures, leading to discomfort or dysfunction (e.g., nerve impingement).

- Cosmetic Concerns: Common driver for presentation, particularly in visible locations.

The clinical presentation of a lipoma is illustrated below.

Risk Factors in the History

- Age: Most common in adults aged 40–60 years; rare in children.

- Sex: Equal overall distribution; angiolipomas and spindle cell lipomas show a slight male predominance (Dabak, 2011).

- Family History: Multiple lipomas may indicate familial lipomatosis or genetic syndromes (e.g., MEN1).

- Associated Conditions: Consider syndromic associations in patients with multiple, deep, or atypical lipomas (e.g., Madelung’s disease).

- Rapid Growth or Recent Change: Raises suspicion for liposarcoma and warrants further investigation.

Lipomas are rarely painful unless associated with nerve involvement or in specific variants like angiolipomas or Dercum’s disease (Charifa, 2018).

Examination

General Characteristics

- Location: Commonly on neck, shoulders, back, and proximal limbs; can appear anywhere, including viscera.

- Number: Usually solitary; multiple lesions suggest syndromic or familial background.

- Size: Varies from millimetres to over 10 cm ("giant lipomas").

- Surface and Shape: Smooth or lobulated; discoid or hemispherical.

- Mobility: Freely mobile in superficial lipomas — demonstrates the “slip sign.”

- Consistency: Soft or rubbery; fluctuant in larger lesions.

Superficial Lipomas

- Subcutaneous, painless, soft, mobile masses.

- Easily palpable with well-defined margins.

Deep-Seated Lipomas

- Less mobile; may involve intramuscular or retroperitoneal spaces.

- More likely to cause compressive symptoms (e.g., paraesthesia, restricted movement).

- Often requires imaging for full assessment.

- Rapid growthSize

- >5 cm

- Deep anatomical location

- Pain or neurological symptoms

- Fixation to underlying structures

The "slip sign" refers to the way a mobile lipoma tends to slide away from the examining finger under gentle pressure.

Differential Diagnosis for Lipoma

Radiologic features, clinical behavior, and histopathology are key to an accurate diagnosis. The following conditions can resemble a lipoma, especially in the initial stages.

- Liposarcoma (Well-Differentiated)

- May mimic lipomas but typically shows non-fatty components, thickened internal septa, or nodular areas on imaging.

- Requires histological confirmation to rule out malignancy.

- Epidermoid or Sebaceous Cysts

- Often tethered to the skin and may have a visible punctum.

- Imaging can show internal debris or calcifications.

- Neurofibromas

- Frequently involve peripheral nerves and may be part of neurofibromatosis.

- MRI may demonstrate a T2 hyperintense signal with a target sign.

- Dermoid Cysts

- Congenital lesions that may contain skin appendages, fat, or even bone or teeth.

- Often appear in midline or periorbital locations and require imaging and histology for confirmation.

- Hematoma

- Usually associated with a history of trauma.

- MRI features change over time depending on blood degradation products.

- Abscess

- Typically painful, erythematous, and warm.

- Imaging reveals a fluid collection with rim enhancement, and aspiration confirms infection

The skin is usually mobile over a lipoma, unlike a sebaceous cyst, where it may be tethered. In intramuscular lipomas, the mass may become less palpable or disappear on muscle contraction.

Imaging for Lipoma

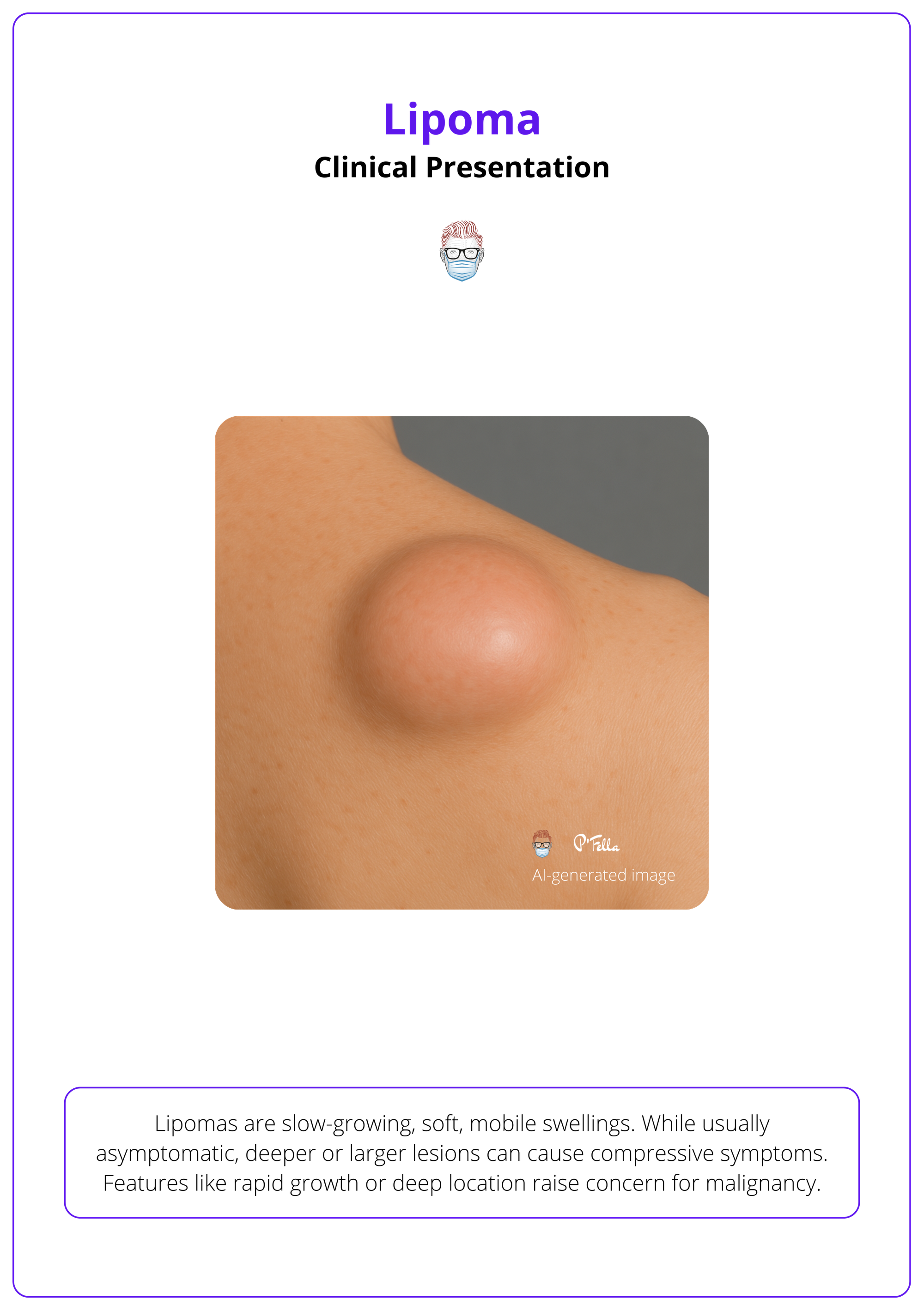

Ultrasound is the preferred initial imaging tool for superficial lipomas, while MRI remains the gold standard for evaluating deep, atypical, or potentially malignant lesions.

Imaging plays a pivotal role in confirming the diagnosis of lipomas, particularly when the presentation is unusual or when the lesion is located deep within soft tissues. It also assists in surgical planning and excluding liposarcoma, a key differential.

- Ultrasound (US)

- First-line modality due to accessibility and cost-effectiveness.

Lipomas typically appear as well-circumscribed, hyperechoic or isoechoic masses. - It helps delineate lesion borders and guide procedures when needed.

- First-line modality due to accessibility and cost-effectiveness.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

- Gold standard for deep, atypical, or complex lesions (Gaskin, 2004).

- Displays homogeneous high signal on T1-weighted images and fat suppression on fat-saturated sequences, indicating a benign fatty nature. It is highly sensitive to tissue composition.

- Computed Tomography (CT)

- Particularly useful in deep or retroperitoneal locations.

- Lipomas show as low-density, well-defined masses and can aid in detecting calcification or deeper invasion not evident on US or MRI.

The image below illustrates the identification of a lipoma in ultrasound.

Lipomas typically show a uniform appearance across imaging modalities. In contrast, liposarcomas may present with thick septa, nodules, or heterogeneous signal patterns-features that warrant biopsy and further investigation (Kransdorf, 2002).

Management of Lipoma

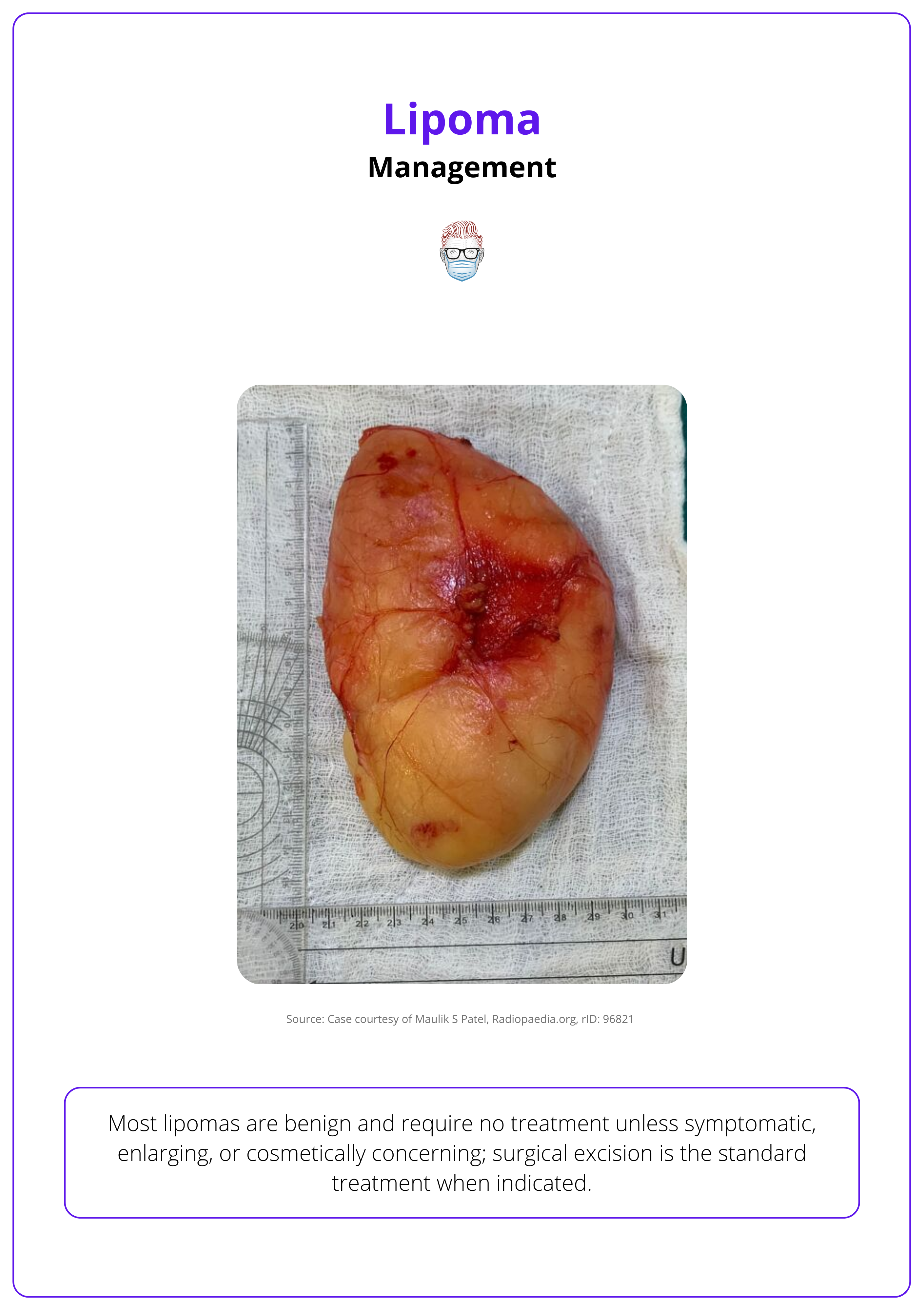

Most lipomas are benign and require no treatment unless symptomatic, enlarging, or cosmetically concerning; surgical excision is the standard treatment when indicated.

Indications for Treatment

While many lipomas are managed conservatively, certain clinical features prompt surgical or procedural intervention.

- Symptomatic Lesions: Pain, tenderness, or restriction of movement may indicate the need for removal. These symptoms often result from compression of adjacent structures.

- Cosmetic Concerns: Patients may request removal for aesthetic reasons, especially for visible or enlarging lipomas.

- Rapid Growth or Atypical Features: Suggestive of malignancy and warrant further evaluation with imaging and possibly biopsy. These cases often proceed to excision for both diagnosis and treatment.

- Large Size or Deep Location: Lipomas in deep or less accessible areas may require imaging-guided assessment and surgical planning.

- Functional Impairment: Lesions that interfere with muscle function, joint movement, or daily activities may justify intervention.

Treatment Modalities

The primary treatment for lipomas is surgical excision, although other options may be considered in select cases.

- Surgical Excision: Most common and definitive treatment. A complete excision, including the capsule, is crucial to prevent recurrence—particularly for deep or intramuscular lipomas, where incomplete removal is more likely.

- Liposuction: Considered for soft, superficial lipomas, especially for cosmetic improvement. May leave residual capsule and has a slightly higher recurrence rate (Boyer, 2015).

- Observation: Appropriate for asymptomatic, stable lesions. Regular monitoring ensures early detection of any change in behavior or appearance.

The image below illustrates a well-encapsulated lipoma excised from the subcutaneous tissue.

Lipomas larger than 5 cm should be evaluated more thoroughly and are often excised or biopsied to confirm diagnosis (Johnson, 2018).

Conclusion

1. Overview: Lipomas are benign tumours of mature fat cells, typically slow-growing and painless. They may be asymptomatic or cause cosmetic or compressive issues depending on size and location.

2. Aetiology: Most lipomas are idiopathic, though some are linked to trauma or genetic syndromes. Histologically, they consist of mature adipocytes and may have variant forms.

3. Clinical Presentation: Lipomas present as soft, mobile, subcutaneous swellings. Deep or rapidly growing lesions, especially those >5 cm, warrant further evaluation for possible malignancy.

4. Imaging: Ultrasound is the first-line tool for superficial lesions, while MRI is used for deeper or atypical cases. Imaging helps rule out liposarcoma by identifying red flag features like nodularity or septations.

5. Differential Diagnosis: Lipomas must be distinguished from liposarcoma, sebaceous cysts, and neurofibromas. Clinical signs, imaging, and histology help confirm diagnosis and rule out malignancy.

6. Management: Small, asymptomatic lipomas can be monitored. Surgical excision is curative and recommended for symptomatic, enlarging, or uncertain lesions; liposuction is an alternative for select cases.

7. Associated Syndromes: Multiple or painful lipomas may signal syndromic associations like Dercum’s disease, familial lipomatosis, or Madelung’s disease. These require systemic evaluation and possible genetic counselling.

Further Reading

- Choi, Joon Hyuk, and Jae Y. Ro. "The 2020 WHO classification of tumors of soft tissue: selected changes and new entities." Advances in anatomic pathology 28.1 (2021): 44-58.

- Yücetürk, G., Sabah, D., Kececi, B., Kara, A. D., & Yalcinkaya, S. (2011). Prevalence of bone and soft tissue tumors. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc, 45(3), 135-43.

- Dabak, N., Yıldız, Y., Demiralp, B., & Keskinbora, M. (2016). Soft tissue tumors. Musculoskeletal Research and Basic Science, 631-638.

- Lemaitre, M., Chevalier, B., Jannin, A., Bourry, J., Espiard, S., & Vantyghem, M. C. (2021). Multiple symmetric and multiple familial lipomatosis. La Presse Médicale, 50(3), 104077.

- Aust MC, Spies M, Kall S, Jokuszies A, Gohritz A, Vogt P. Posttraumatic lipoma: fact or fiction? Skinmed. 2007 Nov-Dec;6(6):266-70. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-9740.2007.06361.x. PMID: 17975353.

- Marques, M. C., and H. Garcia. "Lipomatous tumors." Imaging of soft tissue tumors. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1997. 191-207.

- Creytens, David, et al. "Atypical” pleomorphic lipomatous tumor: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and molecular study of 21 cases, emphasizing its relationship to atypical spindle cell lipomatous tumor and suggesting a morphologic spectrum (atypical spindle cell/pleomorphic lipomatous tumor)." The American Journal of Surgical Pathology 41.11 (2017): 1443-1455.

- Charifa, Ahmad, Chaudhary Ehtsham Azmat, and Talel Badri. "Lipoma pathology." (2018).

- Gaskin CM, Helms CA. Lipomas, lipoma variants, and well-differentiated liposarcomas: Results of MRI evaluations of 126 consecutive fatty masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182(3):733-739.

- Kransdorf, Mark J., et al. "Imaging of fatty tumors: distinction of lipoma and well-differentiated liposarcoma." Radiology 224.1 (2002): 99-104.

- Boyer, M., Monette, S., Nguyen, A., Zipp, T., Aughenbaugh, W. D., & Nimunkar, A. J. (2015). A review of techniques and procedures for lipoma treatment. Clin Dermatol, 3(4), 105-112.

- Johnson, C. N., Ha, A. S., Chen, E., & Davidson, D. (2018). Lipomatous soft-tissue tumors. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 26(22), 779-788.

- Dupuis, H., Lemaitre, M., Jannin, A., Douillard, C., Espiard, S., & Vantyghem, M. C. (2024, June). Lipomatoses. In Annales d'Endocrinologie (Vol. 85, No. 3, pp. 231-247). Elsevier Masson.