Summary Card

Overview

A thorough lower‐limb examination follows the sequence look, feel, move, and neurovascular condition. Always compare both limbs and remember that airway, breathing, and circulation take priority over limb injuries.

How to Examine the Lower Limb

Use a consistent sequence: inspect, palpate, assess movement and power, test nerves, examine vascular status, then scan for limb-threatening conditions. Always compare sides and recheck after any intervention.

Suggested Documentation Template

A structured note ensures consistency, clarity, and early recognition of evolving neurovascular compromise. Document findings systematically under standard headings to create a clear baseline for comparison.

Verified by thePlasticsFella ✅

Overview of Lower Limb Examination

A thorough lower‐limb examination follows the sequence look, feel, move, and neurovascular condition. Always compare both limbs and remember that airway, breathing, and circulation take priority over limb injuries.

The lower limb is a complex structure of bones, muscles, nerves, and vessels. A systematic assessment can reveal subtle signs of compartment syndrome, nerve damage, or vascular injury that require urgent intervention.

Examination begins with inspection for deformity, skin changes, and wounds, followed by palpation for compartment tension and bony tenderness. Movement testing assesses joint range and muscle power, while focused neurological and vascular examinations evaluate nerve function, sensation, and distal pulses.

Document findings carefully and repeat assessments after any intervention.

Key Principles

- Life Over Limb: Even dramatic injuries should not distract from resuscitation and the primary trauma survey. Control bleeding manually and delay definitive limb management until the patient is stable.

- Assessment is Dynamic: Compartment pressures can rise over hours. Reassess neurovascular status frequently and document serial examinations.

- Subtle Signs are Critical: Pain with passive stretch of the compartment muscles is the earliest and most sensitive sign of compartment syndrome. Tense compartments and altered pulses mandate urgent evaluation.

How to Examine the Lower Limb

Use a consistent sequence: inspect, palpate, assess movement and power, test nerves, examine vascular status, then scan for limb-threatening conditions. Always compare sides and recheck after any intervention.

A structured lower-limb examination combines observation, palpation, and targeted functional testing to identify injuries or disease affecting bones, joints, muscles, nerves, and vessels. The goal is to localise pathology while assessing perfusion, stability, and motor integrity.

Inspection

Begin with full exposure from pelvis to toes. Note posture, symmetry, wounds, and skin changes. Observe the gait if the patient can walk. Early pattern recognition can reveal fractures, nerve injuries, vascular insufficiency, or infection.

What to Look for and What it May Mean

- Posture and Symmetry: Limb shortening, external rotation, or abnormal angulation suggest fracture, dislocation, or pelvic injury.

- Gait: Antalgic gait indicates pain. A high-stepping gait suggests foot drop from deep peroneal nerve palsy; a Trendelenburg gait (contralateral pelvic drop) reflects weak hip abductors or superior gluteal nerve injury.

- Skin: Shiny, hairless skin, mottling or pallor point to peripheral arterial disease; erythema, swelling, and blisters raise concern for infection, including necrotising fasciitis.

- Wounds: Document location, depth, and contamination. Exposed bone or tendon suggests an open fracture and possible neurovascular compromise.

- Muscle and Tendon: Wasting, fasciculations, or loss of contour indicate denervation or rupture. Use straight-leg raise and the Thompson test when relevant.

- Bones and Joints: Swelling, malalignment, warmth, or redness can reflect septic arthritis, crystal arthropathy, or dislocation.

When assessing gait, always watch the patient’s pelvis: A Trendelenburg gait (pelvic drop on the opposite side) signals weakness of the hip abductors supplied by the superior gluteal nerve.

Palpation

Palpate compartments, bones, and joints. The combination of a tense compartment and pain on passive stretch is the hallmark of acute compartment syndrome.

Compartment Assessment

- Palpate for tension, swelling, and tenderness.

- Passive stretch tests (pain is an early, specific sign).

- Anterior Compartment: Plantarflex the ankle.

- Lateral Compartment: Invert the ankle.

- Superficial Posterior Compartment: Dorsiflex the ankle.

- Deep Posterior Compartment: Dorsiflex the hallux.

Skeletal and Joint Assessment

- Bones: Tibia, fibula, femur, and pelvis for point tenderness or crepitus, which localise fractures.

- Joints: Hips, knees, ankles, and toes for effusion or instability, suggesting septic arthritis, synovitis, or ligamentous injury.

Pain on passive stretch is the earliest and most reliable sign of compartment syndrome. It appears long before loss of pulse or paralysis.

Move

Assess active range of motion at each joint, then test strength against resistance. Compare with the contralateral limb. Evaluate tone by passively moving the relaxed limb.

- Tone: Hypertonia suggests an upper motor neuron lesion. Hypotonia suggests a lower motor neuron or acute root lesion.

- Hip: Test flexion, extension, abduction, and rotation. Weak abduction may produce a Trendelenburg sign.

- Knee: Test flexion and extension. If the range is limited, evaluate for instability.

- Ankle: Test dorsiflexion, plantarflexion, inversion, and eversion. Loss of dorsiflexion suggests a deep peroneal nerve lesion.

- Toes: Great-toe dorsiflexion assesses deep peroneal function.

- Power (MRC 0-5)

- 0 - no contraction

- 1 - flicker

- 2 - active movement with gravity eliminated

- 3 - active movement against gravity

- 4 - movement against gravity and resistance

- 5 - normal power

Nerve Assessment

Test motor function, key sensory areas, and reflexes. Correlate deficits with root levels and specific peripheral nerves.

Motor and Mixed Nerves

- Femoral: Hip flexion (L2-L3), knee extension (L3-L4). Test resisted hip flexion and resisted knee extension.

- Sciatic: Knee flexion (L5-S1). Test resisted knee flexion.

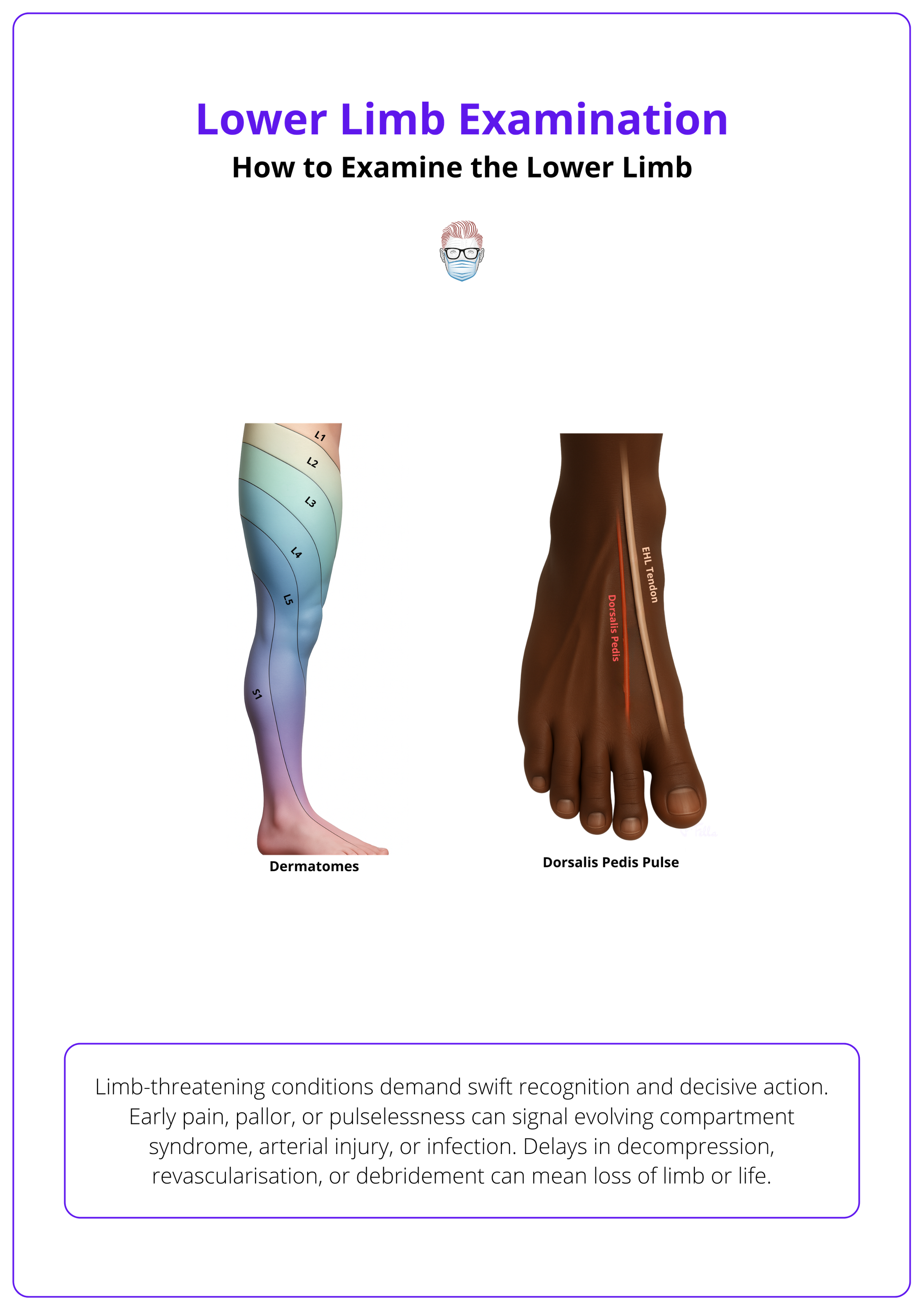

- Deep Peroneal (deep fibular): Ankle dorsiflexion and great-toe extension (L4-L5/L5). Test resisted dorsiflexion and EHL extension. Sensory check in the first web space.

- Superficial Peroneal: Foot eversion. Sensory over most of the dorsum of the foot except the first web space. Test resisted eversion and light touch on the dorsum.

- Tibial: Plantarflexion and toe flexion (S1-S2). Test calf raise and toe flexion. Check plantar sensation.

- Superior gluteal: Hip abduction (L4-S1). Test single-leg stance or resisted abduction.

- Inferior gluteal: Hip extension (L5-S2). Test resisted extension.

Pure Sensory Nerves

- Saphenous: Medial leg and foot.

- Sural: Lower lateral leg, lateral heel, ankle, and lateral dorsum of foot.

Sensory Modalities and Reflexes

- Use cotton wool or a neurotip for light touch and pinprick, a tuning fork for vibration, and move the toes up and down for proprioception.

- Reflexes: Patellar (L3-L4) and Achilles (S1-S2). A positive Babinski (upgoing plantar) indicates an upper motor neuron lesion.

The deep peroneal nerve supplies only a small patch of skin: the first dorsal web space, yet testing this area is crucial, as loss of sensation here is one of the earliest indicators of anterior compartment syndrome.

Vascular Examination

Palpate distal pulses and document strength on a 0 to 4+ scale. Compare sides and reassess after splinting, manipulation, or surgery. Pulses can still be palpable even when compartment pressures are high.

Pulse Landmarks and Practical Tips

- Femoral: Just distal to the inguinal ligament, a little medial to the midpoint between the pubic symphysis and ASIS. Often the most informative pulse during resuscitation.

- Popliteal: In the popliteal fossa, slightly lateral to midline. Flex the knee slightly and use both hands.

- Posterior Tibial: Immediately posterior to the medial malleolus; can be difficult for novices.

- Dorsalis Pedis: Dorsum of the foot, lateral to the EHL tendon and within about a centimetre of the navicular. It may be absent in a minority of healthy people; asking the patient to extend the great toe helps locate the tendon.

Also assess capillary refill time (aim for under two seconds) and skin temperature. In trauma or suspected vascular injury, bedside Doppler and calculation of the ankle-brachial index can aid diagnosis.

A palpable pulse does not rule out compartment syndrome. Arterial flow may persist even when microvascular perfusion is compromised by high compartment pressures.

Limb-Threatening Conditions

Recognise early features and act without delay. Rapid decisions prevent limb loss and reduce mortality.

- Acute Compartment Syndrome: Early pain on passive stretch with or without a tense compartment. Aim for decompression within six hours. Perform a two-incision, four-compartment fasciotomy of the leg when indicated.

- Major Arterial Injury: Pale, cold, pulseless limb. Proceed to immediate temporary shunting or definitive revascularisation, with consideration of systemic heparinisation if appropriate.

- Open Fracture or Open Joint: Visible communication between the bone or joint and skin. Give intravenous antibiotics within one hour, perform early debridement, and achieve soft-tissue coverage within about 72 hours.

- Necrotising Fasciitis: Rapid progression with erythema, swelling, and haemorrhagic or yellow fluid–filled blisters. Treat as a surgical emergency with broad-spectrum antibiotics and urgent debridement.

- Crush Syndrome: Rising creatine kinase, dark urine, and hyperkalaemia after extrication. Begin aggressive intravenous fluids, consider urine alkalinisation, treat hyperkalaemia, and monitor renal function closely.

Dermatomes and dorsalis pedis pulse are illustrated below.

Compartment syndrome becomes limb-threatening when compartment pressure approaches diastolic pressure. A delta pressure (diastolic minus compartment) < 30 mmHg is considered diagnostic and mandates fasciotomy.

Suggested Documentation Template

A structured note ensures consistency, clarity, and early recognition of evolving neurovascular compromise. Document findings systematically under standard headings to create a clear baseline for comparison.

When examining the lower limb, documentation should capture both what is normal and what requires ongoing review. Recording a thorough baseline helps detect subtle changes, especially in trauma, vascular, or postoperative settings.

The following template demonstrates concise, clinically useful phrasing for a normal neurovascular examination.

- Inspection: No deformity, wounds, or erythema. Skin warm and pink with normal hair distribution.

- Palpation: Compartments soft and non-tender with no pain on passive stretch. Bones non-tender.

- Sensation: Intact across dermatomes L2-S2. Saphenous and sural territories are normal.

- Motor (MRC): Power 5/5 in hip, knee, ankle, and toe movements with normal tone.

- Pulses: Femoral, popliteal, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibial pulses are palpable and symmetrical. Capillary refill <2 seconds.

- Reflexes: Patellar and Achilles reflexes present and symmetrical. Plantar responses down-going.

- Plan: Repeat neurovascular assessment one hour after splint application and monitor for swelling or increasing pain.

Conclusion

1. Overview: Use a structured lower limb assessment - look, feel, move, neurovascular while prioritising airway, breathing, and circulation in trauma.

2. Examination Sequence: Begin with inspection, then palpate compartments and bones, test movement and tone, assess nerves and reflexes, and check vascular status.

3. Notice Red Flags: Early pain on passive stretch, tense compartments, or altered pulses may signal compartment syndrome or vascular injury.

4. Pulse ≠ Perfusion: Palpable pulses do not rule out ischaemia. Compartment pressure can still compromise microvascular flow. Repeat neurovascular checks.

5. Suggested Documentation: Record inspection, palpation, sensation, motor strength, pulses, and reflexes. Reassess and document neurovascular status serially.

Further Reading

- American College of Surgeons (2018) ATLS. Advanced Trauma Life Support Manual. 10th edn. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons.

- Sharma, S. and Hashmi, M.F. (2024). Peripheral pulse. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

- Physiopedia (n.d.) Myotomes.

- Physiopedia (n.d.) Sural nerve & saphenous nerve.

- Cleveland Clinic (2024). Necrotizing fasciitis: causes, symptoms & treatment.