Summary Card

Overview

Perineal reconstruction addresses soft tissue defects with the aim of restoring anatomy, preserving function, and reducing postoperative complications, particularly in complex or contaminated wounds.

Indications

Malignancy is the most common indication for perineal reconstruction, often following oncologic resection and radiation. Other causes include trauma, infection, and congenital or functional defects.

Reconstructive Principles

Perineal reconstruction is uniquely challenging due to the complex anatomy, high bacterial burden, risk of pressure necrosis, and involvement of critical urogenital and anorectal functions.

Procedure

The reconstructive approach to perineal defects must be guided by defect complexity, prior radiation, risk of contamination, and patient-specific functional needs.

Complications

Perineal reconstruction carries a high risk of wound-related complications due to the region’s bacterial load, mobility, and proximity to the gastrointestinal and urogenital tracts.

Primary Contributor: Dr Hatan Mortada, Educational Fellow

Verified by thePlasticsFella ✅

Overview of Perineal Reconstruction

Perineal reconstruction addresses soft tissue defects with the aim of restoring anatomy, preserving function, and reducing postoperative complications, particularly in complex or contaminated wounds.

Perineal reconstruction is the surgical restoration of defects in the perineal region using local, regional, or free flaps. The goal is to provide durable, vascularised perineal reconstruction to restore anatomy, eliminate dead space, and enable early mobilisation. These defects may result from:

- Oncologic resections (e.g., abdominoperineal resection, pelvic exenteration)

- Infective conditions (e.g., Fournier’s gangrene)

- Traumatic injuries

- Congenital or chronic inflammatory diseases

The boundaries of the perineum include:

- Anterior: Pubic arch and arcuate ligament

- Posterior: Tip of the coccyx

- Lateral/Medial: Inferior pubic rami and ischial tuberosities

- Superior: Pelvic floor

- Inferior: Perineal skin and fascia

Gender-Specific Structures

- Female: Vulva (mons, labia, clitoris, vestibule), vagina

- Male: Penis (root, shaft, glans), scrotum (testes, epididymis, ductus deferens)

The perineum's complex anatomy, constant motion, and proximity to vital structures make durable flap selection critical for successful reconstruction.

Indications of Perineal Reconstruction

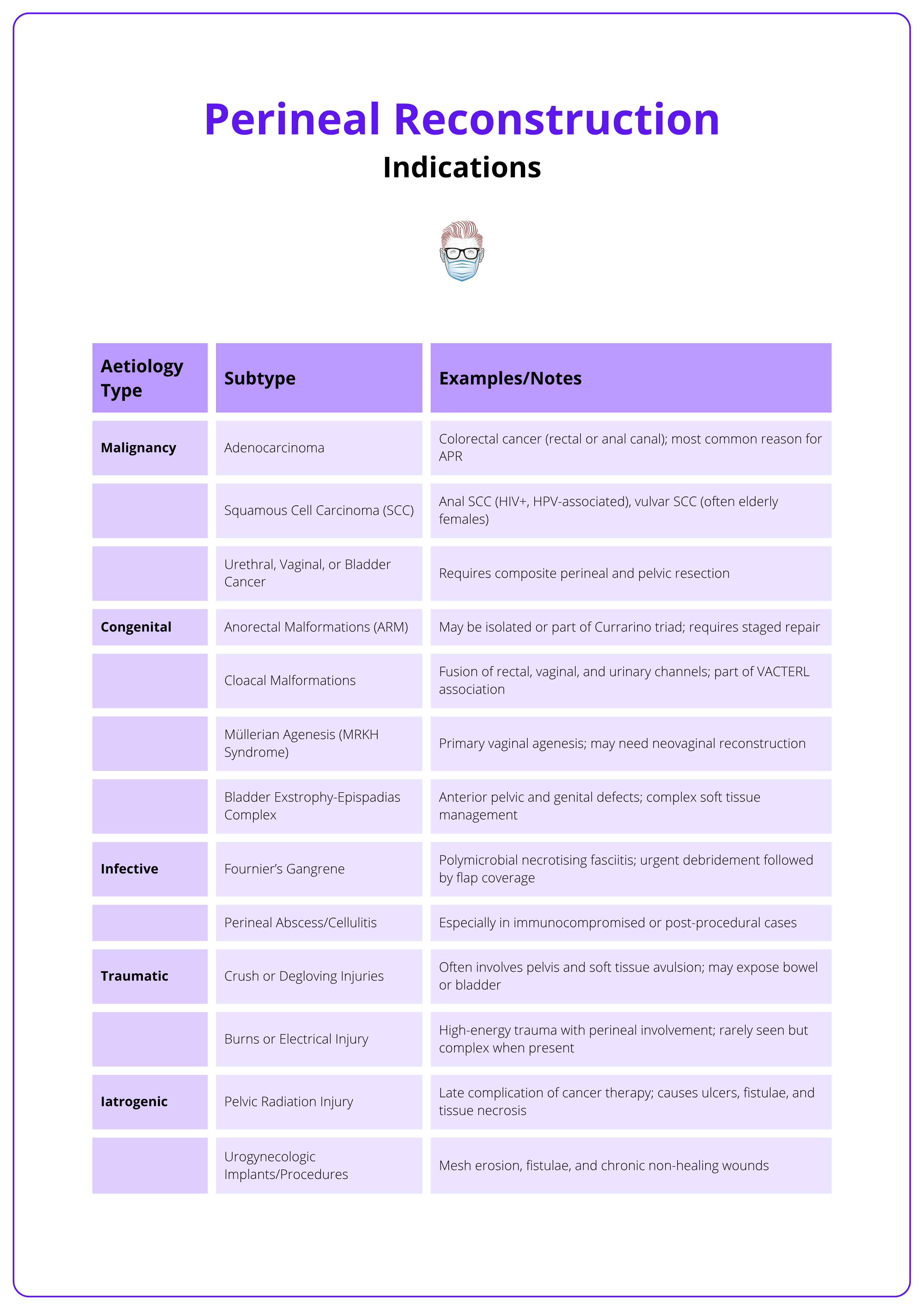

Malignancy is the most common indication for perineal reconstruction, often following oncologic resection and radiation. Other causes include trauma, infection, and congenital or functional defects.

Perineal defects occur in a range of conditions and require tailored reconstructive strategies (Salgado, 2011). The goal is to provide durable, vascularised coverage to support healing and restore function.

Oncologic

This is the most frequent and complex indication for reconstruction. It often involves skin, anus, vulva, vagina, penis, and adjacent soft tissue and frequently complicated by radiation therapy, impairing wound healing. Key scenarios include,

- Abdominoperineal resection (APR) for low rectal or anal cancer.

- Pelvic exenteration (removal of pelvic organs).

- Vulvectomy or penectomy requiring genital reconstruction.

- Rectovaginal or rectourethral fistulae, often from malignancy or radiation.

Traumatic

These injuries are typically due to severe mechanisms such as pelvic fractures or industrial accidents. They may involve:

- Crush injuries or degloving wounds, with exposure of pelvic organs and structures.

Infective

Commonly seen in diabetic or immunocompromised patients, these infections include:

- Fournier’s gangrene is the most frequent cause in this group.

- Necrotising fasciitis requires staged wound management and infection clearance prior to definitive repair.

Congenital and Functional

- Anorectal malformations, such as cloacal anomalies, requiring staged flap-based procedures.

- Chronic radiation wounds. Seen in cancer survivors, often complicated by fibrosis and ulceration.

The table below summarises aetiologies of perineal defects and their reconstructive implications.

When dealing with rectovaginal fistulae, a core principle is to excise the fistula tract and interpose well-vascularised tissue between the cavities. Muscle flaps like gracilis are often ideal in these scenarios.

Principles of Perineal Reconstruction

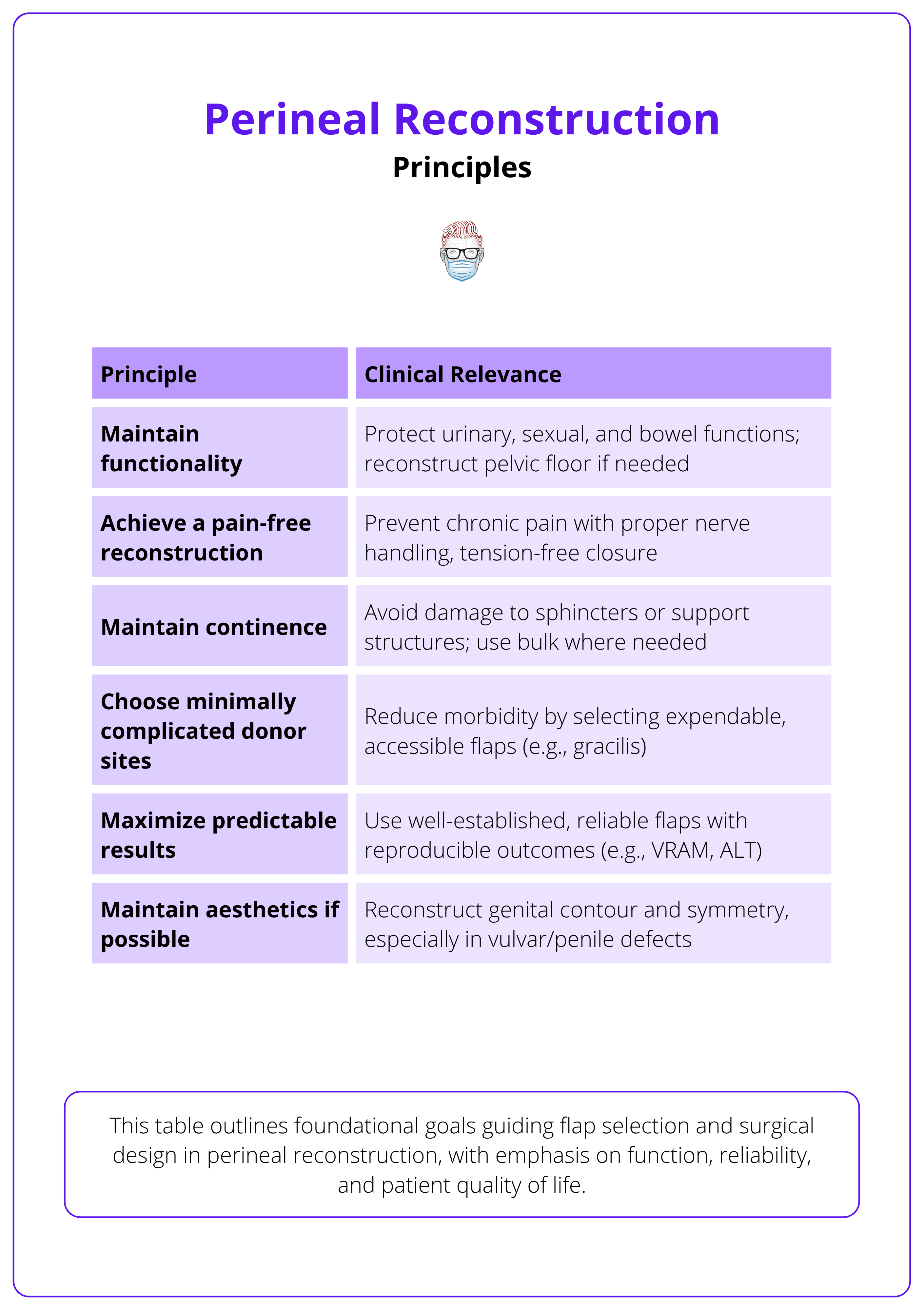

Perineal reconstruction is uniquely challenging due to the complex anatomy, high bacterial burden, risk of pressure necrosis, and involvement of critical urogenital and anorectal functions.

Effective perineal reconstruction balances three key demands: matching the flap to the defect, withstanding hostile wound environments, and minimizing donor site complications. Every choice should reflect this balance between defect needs and donor site trade-offs.

General Considerations

Perineal reconstruction presents distinct challenges compared to other regions, such as the lower limb, due to the following unique factors.

- Multisystem Involvement: Often includes the anus, vulva, vagina, or penis (Butler, 2005).

- Dual Goals: Requires restoration of both form and function.

- High Bacterial Load: Increases risk of infection and wound breakdown.

- Pressure Risk: Recumbent/sitting positions can cause ischemia and flap necrosis.

- Mechanical Tension: Ambulation stresses incisions and closures.

- Dead Space: Especially after pelvic resections, requires careful obliteration.

- Local Environment: Moisture, friction, and proximity to urine/feces complicate healing (Salgado, 2011).

The table below summarises foundational goals guiding flap selection and surgical design in perineal reconstruction.

Specific Considerations

Tissue Selection by Defect and Function

Flap choice must balance structural needs with long-term donor site impact.

- Superficial Defects (e.g., hidradenitis, minor trauma): Use local advancement or fasciocutaneous flaps. Minimal morbidity, fast recovery.

- Deep/Complex Defects (e.g., malignancy, trauma): Require muscle or myocutaneous flaps to fill dead space and withstand radiation.

- Gracilis: Reliable, low functional loss.

- VRAM: High bulk, suited for major resections; risk of abdominal wall weakness.

- Gluteal: Posterior coverage; may limit sitting/mobility.

Contamination, Radiation, and Oncologic Fields

- Infected/Irradiated Fields: Muscle flaps are preferred for perfusion and resistance to infection (Nelson, 2009). Gracilis: Ideal for moderate contaminated defects, VRAM: Best for extensive, irradiated, or composite loss.

- Benign Cases: Delay reconstruction until wound is clean and stable (Salgado, 2011).

- Malignant Cases: Require multidisciplinary input and flaps that restore compartmental integrity and resist breakdown.

Flap choice must account for defect characteristics, contamination, functional demands, and donor morbidity. Gracilis and VRAM are preferred in contaminated or irradiated fields for their vascularity and reliability.

Procedure of Perineal Reconstruction

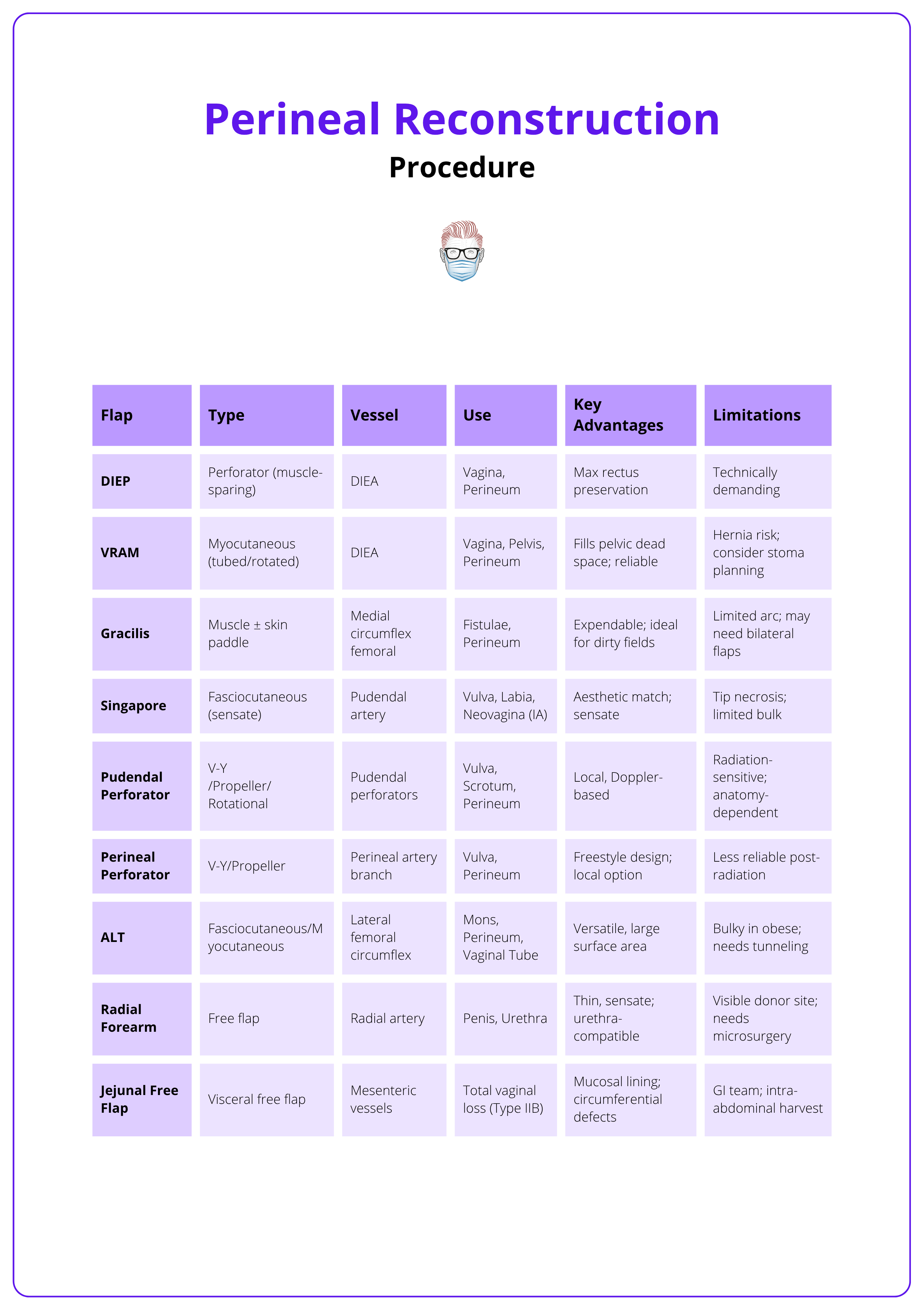

The reconstructive approach to perineal defects must be guided by defect complexity, prior radiation, risk of contamination, and patient-specific functional needs.

Pedicled flaps remain the cornerstone due to their reliability, proximity, and ability to fill pelvic dead space with vascularised tissue.

Pre-Operative Planning

Optimisation

- Nutrition: Optimise in all patients; low albumin correlates with poor healing.

- Bowel Prep: Recommended prior to oncologic resections.

- Stoma Planning: Diverting stoma should be considered in high-risk or contaminated wounds.

Multidisciplinary Coordination

- Involve colorectal, gynaecologic oncology, and urology teams.

- Joint planning anticipates: Pelvic dead space, Flap design, Stoma location relative to flap pedicles

Flap Design

Defect Assessment

Key factors to evaluate in perineal reconstruction:

- Size and Depth of the defect.

- Exposure of critical structures (e.g., urethra, bowel, sacrum).

- Radiation History or presence of chronic infection.

- Volume of Pelvic Dead Space.

- Anatomic Location: Anterior, posterior, or circumferential.

Reconstructive Planning

- Superficial, Dry, Non-Irradiated Wounds: Consider skin grafts or local fasciocutaneous flaps.

- Deep, Contaminated, or Irradiated Wounds: Muscle or myocutaneous flaps preferred for bulk and perfusion.

Technique

Skin Grafts

- Suitable for uncomplicated superficial wounds only.

- Poor durability in moist or high-shear areas.

- Avoid over-bone, vessels, or irradiated tissue.

Regional and Pedicled Flaps

- Gracilis Muscle Flap

- Indication: Moderate defects in contaminated/irradiated fields.

- Blood Supply: Medial circumflex femoral artery.

- Pros: Easy to harvest, low donor morbidity, effective for fistulae.

- Cons: Limited arc of rotation; may need bilateral flaps for large volumes.

- Vertical Rectus Abdominis Myocutaneous (VRAM) Flap

- Indication: Large or post-APR perineal/vaginal defects.

- Blood Supply: Deep inferior epigastric artery.

- Design: Vertical, transverse, or oblique.

- Applications

- Vaginal wall reconstruction (can be tubed).

- Obliterating pelvic dead space.

- Notes

- Preserve the anterior rectus sheath to reduce hernia risk.

- Preserve the contralateral rectus if a stoma is planned.

- Can be tunneled or rotated retroperitoneally.

- Anterolateral Thigh (ALT) Flap

- Blood Supply: Descending branch of the lateral femoral circumflex artery.

- Use: Large, irradiated, or abdominally inaccessible defects.

- Technique Tip: Tunnel deep to the rectus femoris to increase reach.

- Considerations: Perforator variability; may be bulky in obese patients.

- Gluteal and Posterior Thigh Flaps

- Blood Supply: Inferior gluteal artery or profunda perforators.

- Indication: When abdominal options are contraindicated.

- Use: Posterior perineal coverage; V-Y or rotation flaps for unilateral defects.

- Pudendal Thigh (Singapore) Flap

- Blood Supply: Branches of pudendal artery.

- Indication: Vulvar, labial, or periclitoral reconstruction.

- Advantage: Sensation preserved, which is important for function and quality of life.

- Use: Ideal for Type IA vaginal defects (Nelson, 2009).

Free Flap Reconstruction

- Reserved for complex or salvage cases

- Circumferential vaginal defects.

- Failed prior reconstruction.

- Examples

- Free Jejunal Flap: Used for Type IIB defects (total vaginal loss).

- Recipient Vessels: Gluteal or femoral; may require vein grafts.

The table below summarises key flap types by indication, vascular supply, major benefits, and technical challenges.

Vaginal Defect Classification

When vaginal reconstruction is required — particularly following oncologic resection, radiation, or extensive perineal injury — the Cordeiro classification helps guide flap selection based on the extent and location of tissue loss (Cordeiro, 2002).

- Type I: Partial defects

- IA: Anterior or lateral wall

- IB: Posterior wall

- Type II: Circumferential defects

- IIA: Upper two-thirds

- IIB: Total vaginal loss

The image below illustrates the Cordeiro system for classifying acquired vaginal defects.

Reconstructive Options by Type

- Type IA: Singapore flap or local perforator-based fasciocutaneous flaps.

- Type IB and IIA: Pedicled VRAM flap (tubed or inset).

- Type IIB: Bilateral gracilis or VRAM flaps, or free jejunal flap for full neovaginal tube.

Post-Operative Care

Positioning and Pressure Management

- Avoid direct pressure over the flap (especially posteriorly).

- Place in low Fowler’s or lateral decubitus positions early post-op.

- Minimise sitting for the first 10-14 days.

Drain Management

- Insert closed-suction drains under the flap and in the pelvic dead space.

- Prevents seroma, promotes adherence of flap to bed.

Stoma Considerations

- Plan the ostomy away from flap pedicles.

- Ensure stoma appliance adhesion is not compromised by adjacent incisions.

Mobilization

- Early ambulation is encouraged once flap integrity is confirmed.

- Use foam cushions or pressure-relieving supports (Salgado, 2011).

The VRAM flap is preferred for obliterating pelvic dead space post-APR. Preserve the anterior rectus sheath during harvest to reduce hernia risk, and coordinate with general surgery for optimal pedicle orientation if a colostomy is planned.

Complications and Outcomes of Perineal Reconstruction

Perineal reconstruction carries a high risk of wound-related complications due to the region’s bacterial load, mobility, and proximity to the gastrointestinal and urogenital tracts.

Vigilant post-operative care and pressure avoidance are essential to reduce morbidity and flap loss.

Common Complications

Wound Dehiscence

The most frequent postoperative complication, especially in irradiated fields, often caused by shear, pressure, or patient mobility.

- Small dehiscences may heal secondarily with conservative management.

- Larger wounds or those compromising adjuvant therapy may require surgical revision.

Infection

The perineum's high bacterial burden makes infection a significant risk.

- Closed-suction drains should be maintained as long as needed to avoid seroma and abscess.

- If sepsis occurs, deep pelvic abscesses must be excluded and drained.

Flap Necrosis

Total flap loss is rare with pedicled options, but requires prompt recognition. Partial necrosis may occur due to venous congestion or pedicle compression, especially in,

- VRAM Flaps: Vulnerable to venous outflow issues in deep pelvic tunnels.

- Gracilis Flaps: Large skin paddles may develop fat necrosis; muscle belly may retract if disrupted.

- Singapore Flaps: Tip necrosis is a known risk, especially with poor perfusion.

Perineal Hernia

This occurs when the pelvic dead space is inadequately obliterated, especially post-APR. Prevention includes:

- Use of bulky flaps (e.g., VRAM).

- Layered closure of pelvic floor fascia if intact.

Flap-Related Considerations

- Patients must be positioned to avoid direct pressure on the flap site post-operatively.

- Early ambulation is encouraged, but sitting should be avoided for 4-6 weeks to prevent shear-related ischemia.

- Vigilant monitoring of flap perfusion is necessary, particularly in the first 48-72 hours.

Functional Outcomes

Long-term functional success extends beyond wound closure.

- Urinary and fecal continence may be impacted, especially if pelvic floor support is inadequate.

- Vaginal reconstruction complications include,

- Inadequate neovaginal dimensions.

- Vaginal stenosis or dryness.

- Hypertrophic scarring or psychological distress impacting sexual function.

- Sexual outcomes may not correlate with anatomical reconstruction alone. Psychosocial support is often necessary.

Without flap-based reconstruction, perineal wound complications following abdominoperineal resection can reach 40-66%, particularly in patients who received neoadjuvant chemoradiation. Flaps like the VRAM significantly reduce this risk by filling dead space and improving healing in irradiated fields.

Conclusion

1. Overview: Perineal reconstruction restores anatomy and function after oncologic resection, trauma, or infection, using vascularised tissue to reduce complications.

2. Indications and Anatomy: Most common after pelvic cancer surgery, the perineum’s complex anatomy and high contamination risk demand tailored reconstructive approaches.

3. Reconstructive Principles & Flap Selection: Flap choice depends on depth, contamination, and functional goals—VRAM and gracilis are mainstays; ALT and Singapore flaps suit select cases.

4. Procedure & Post-Op Care: Surgical planning must address dead space, flap orientation, and stoma sites; avoid pressure on flaps and mobilise early post-op.

5. Complications & Outcomes: Risks include wound dehiscence, infection, flap failure, and functional issues; long-term outcomes depend on technique and post-op care.

Further Reading

- Cordeiro PG, Pusic AL. A Classification System and Reconstructive Algorithm for Acquired Defects of the Vagina. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(5):1058–1065. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000181385.19011.52

- Fix RJ, TerKonda SP, Zinsser J, Vasconez LO. Reconstruction of the abdomen and perineum in cancer surgery. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 1997;6(1):115-132.

- Nelson RA, Butler CE. Surgical Outcomes of VRAM Flap Reconstruction for Perineal and Pelvic Defects: A 10-Year Experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(8):2263–2271. doi:10.1245/s10434-009-0502-1

- van Ramshorst GH, Young JM, Solomon MJ. Complications and Impact on Quality of Life of Vertical Rectus Abdominis Myocutaneous Flaps for Reconstruction in Pelvic Exenteration Surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63(9):1225-1233. doi:10.1097/DCR.0000000000001632

- Chim H, Salgado CJ, Mardini S. Reconstruction of Perineal and Genitourinary Defects. In: Neligan PC, ed. Plastic Surgery. 4th ed. Vol 6. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:407–430.

- Koshy JC, Goldberg JS, Agarwal S, et al. Perineal and Lower Extremity Reconstruction. In: Thorne CH, ed. Grabb and Smith’s Plastic Surgery. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2014:872–880.

- Losken A, Carlson GW, Jones GE, et al. Perineal and Posterior Vaginal Wall Reconstruction Using the Gluteal Fold Flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(3):734–739. doi:10.1097/00006534-200103000-00020

- Weichman KE, Matros E, Disa JJ. Reconstruction of Peripelvic Oncologic Defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140(4):601e-612e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000003703

- Lin CT, Chang SC, Chen SG, Tzeng YS. Reconstruction of perineoscrotal defects in Fournier's gangrene with pedicle anterolateral thigh perforator flap. ANZ J Surg. 2016;86(12):1052-1055. doi:10.1111/ans.12782

- Mughal M, Baker RJ, Muneer A, Mosahebi A. Reconstruction of perineal defects. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2013;95(8):539-544. doi:10.1308/rcsann.2013.95.8.539