Research Methods in Plastic Surgery

This chapter offers a comprehensive overview of the most relevant research methods, structured to help trainees and clinicians critically appraise evidence, select appropriate designs, and contribute meaningfully to the evolving plastic surgery literature.

- Study Design Overview

- Observational Studies

- Experimental Studies

- Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- Patient-Centred Research Methods

- Improving the Quality of Research

Primary Contributors: Suraya Yusuf & Justin Conrad Rosen Wormald

Verified by thePlasticsFella ✅

Study Design Overview

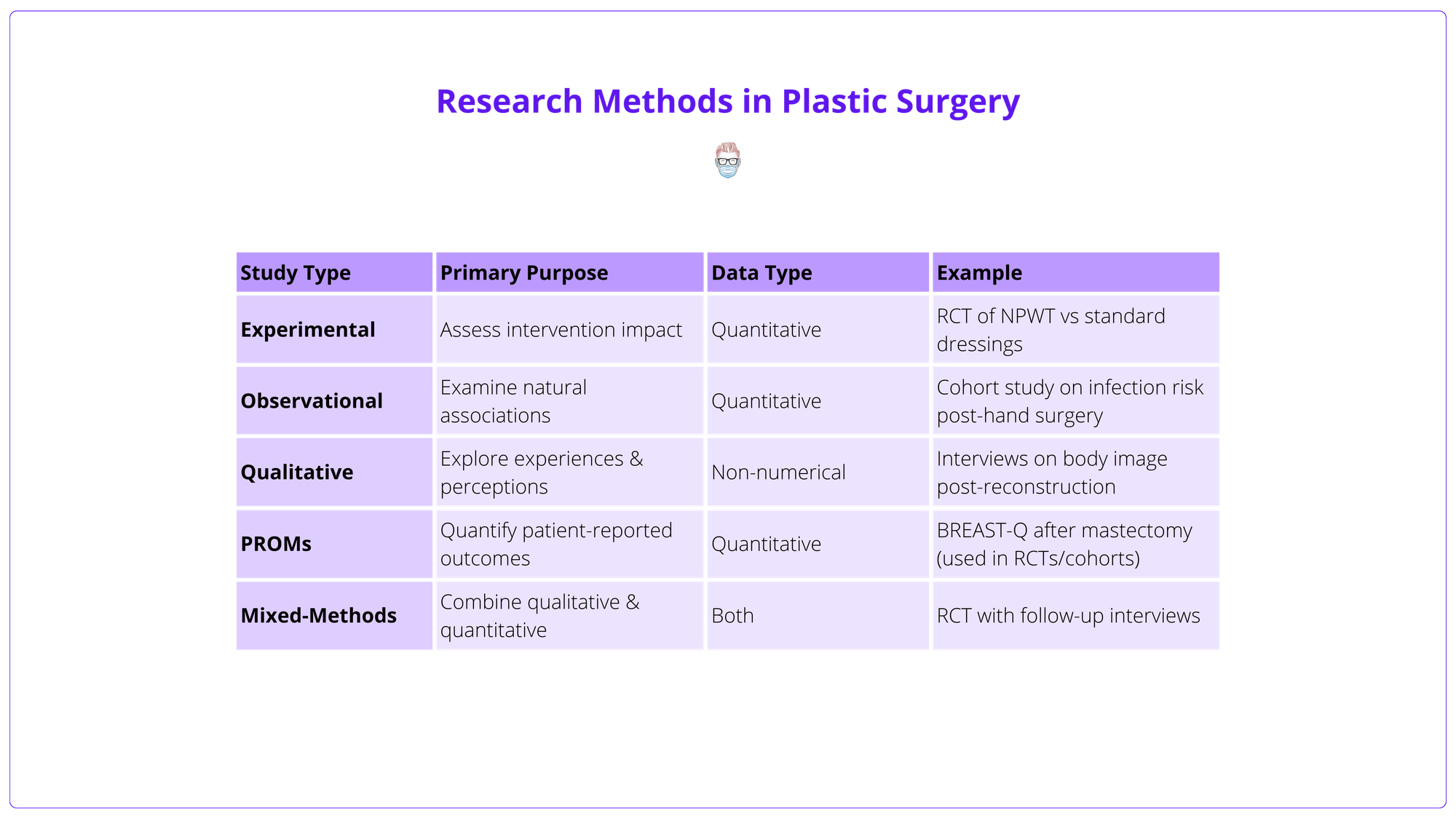

Study design determines what question can be asked, how it is answered, and how robust and generalisable the results will be. At the highest level, research design divides into two core types.

- Observational Studies: Examine existing data or naturally occurring exposures without intervention.

- Experimental Studies: Involve deliberate intervention and prospective outcome measurement.

- Other: These include qualitative, PROMS, and a combination/mixed-methods.

Study types, their characteristics, and examples are detailed in the table below.

Observational Studies

Observational studies are the foundation of most plastic surgery research. Unlike experimental studies, they do not involve interventions but instead examine existing data to explore patient characteristics, outcomes, and associations.

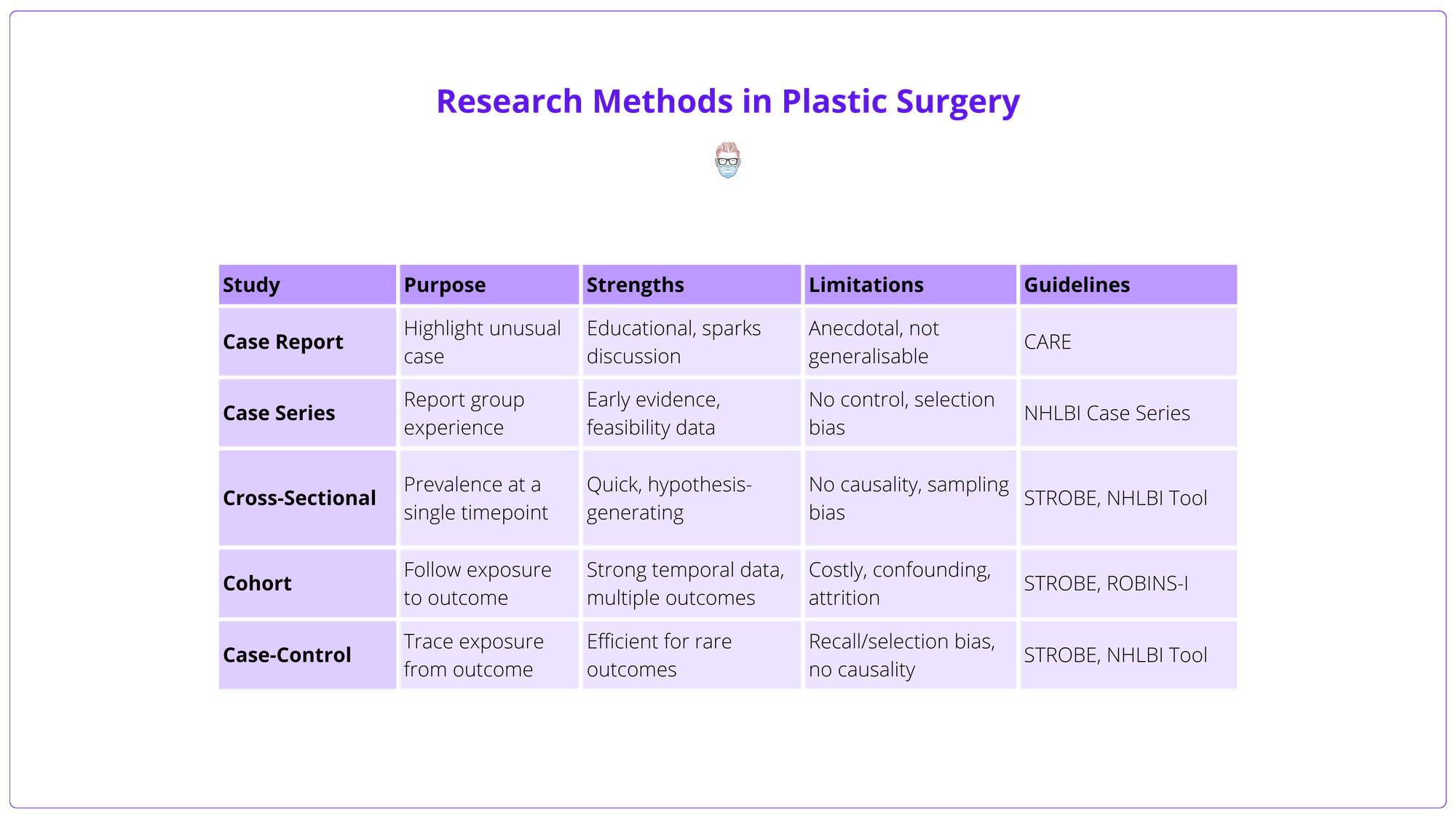

They are generally classified into two categories.

- Descriptive studies, such as case reports and case series.

- Analytical studies, including cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort designs.

The table below summarises the key types of observational studies.

Observational Descriptive Studies

These describe clinical features or outcomes without comparing groups.

Case report

- Purpose: Describes a single patient’s unique or rare presentation, management, or outcome.

- When to Use: Highlight novel or high-risk conditions; stimulate further research.

- Example: Yusuf et al. (2025) reported a rare case of necrotising myositis, underscoring diagnostic challenges and surgical urgency.

- Limitations: Anecdotal; prone to bias.

- Guideline: CARE Guidelines.

Case series

- Purpose: Describes outcomes in a group with similar features or interventions.

- Common Use: Reporting early results of novel techniques before formal evaluation.

- Example: Euwen et al (2025) demonstrated Botulinum Toxin A for ischaemic feet in Raynaud’s syndrome.

- Pros/Cons: Offers early safety and feasibility data, lacks a control group; prone to selection bias.

- Guideline: NHLBI Case Series Tool.

Consecutive case series are more robust than selective ones.

Observational Analytical Studies

These compare groups to identify relationships between exposures and outcomes.

Cross-Sectional Studies

A snapshot of outcome and exposure at a single time point; useful for prevalence estimates.

- Purpose: Examine a population at a single time point to assess disease prevalence or patient characteristics.

- Examples: Patient satisfaction after implant or autologous tissue breast reconstruction (Pirro et al, 2017).

- Pros/Cons: Fast and efficient; useful for generating hypotheses, no causality inference as there is no longitudinal follow-up; may suffer from sampling bias if the samples are not representative of the wider population.

- Guideline: NHLBI Cohort & Cross-Sectional Tool, STROBE Statement.

Cohort Studies

Follows exposed and unexposed groups over time; can establish a temporal relationship, but may be time-consuming and costly.

- Purpose: Follow patients over time to assess how exposure(risk factor or intervention) affects outcomes (prospective or retrospective).

- Example: Davis et al (2020): Prospective multicentre study on infection risk with delayed hand surgery.

- Pros/Cons: Strong for studying incidence and temporal relationships, prone to confounding; expensive; high attrition risk; can study multiple outcomes within one cohort to maximise efficiency.

- Guidelines: NHLBI Appraisal Tool, STROBE Statement, Consider ROBINS-I Tool for non-randomised bias assessment.

Use standardised protocol templates and reporting guidelines when developing studies.

Case-Control Studies

Retrospective comparison of subjects with and without outcome; efficient for rare outcomes but at risk of recall and selection bias.

- Purpose: Case-control studies compare individuals with a specific outcome (cases) to those without (controls), assessing past exposures to identify potential risk factors. This outcome-to-exposure approach makes case-control studies ideal for rare outcomes or long latency periods, avoiding the time and cost of tracking large cohorts over time.

- Example: Hsiung et al. (2024) - Compared patients with and without flap failure post-free tissue transfer to identify risk factors.

- Pros/Cons: Case-control studies are efficient for exploring potential associations but cannot establish causality. They rely on historical data, making them prone to recall and measurement bias — especially with self-reported exposures. Accurate control selection is crucial, as poor matching can distort results.

- Guideline: NHLBI Case-Control Tool, always align with STROBE Statement.

These studies are best suited for hypothesis generation and should ideally be followed by prospective research.

Experimental Studies

Unlike observational designs, experimental studies involve active intervention by the researcher. They are typically prospective and aim to evaluate the efficacy, safety, cost-effectiveness, or impact of a treatment or surgical approach.

Experimental studies can be either randomised or non-randomised.

Non-Randomised Studies of Interventions (NRSIs)

Also known as quasi-experimental studies, these deliver an intervention but lack random allocation.

- Purpose: To assess treatment effects in real-world settings where randomisation is not feasible. It offers causal insights.

- Example: Comparing surgical site infection rates before and after introducing a new antibiotic protocol.

- Pros/Cons: More pragmatic and often used in quality improvement. Prone to confounding and bias; can offer causal inferences, though less robust than RCTs and highly dependent on design quality and confounding control.

- Risk of Bias Tool: Use ROBINS-I for appraisal.

Consider ethical approval requirements and patient involvement from the planning stage.

Randomised Control Trials (RCTS)

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) provide the highest level of clinical evidence by using random allocation to reduce bias and allow causal inference. Randomisation helps equalise confounding variables across groups, but small sample sizes can still lead to imbalances by chance.

Key Features

- Randomisation: Reduces selection bias and balances known/unknown confounders. Small sample sizes can still lead to chance imbalances.

- Blinding: Minimises performance and detection bias. Challenging in surgical trials due to visible differences between procedures. Sham surgeries may be used, but raise ethical concerns. Bias can be further reduced through blinding, where participants, investigators, or both (‘double-blinding’) are unaware of group allocation.

- Equipoise: Ethical justification requires genuine uncertainty about which treatment is superior. For example, the BRAVE study highlighted surgeon resistance to randomisation due to personal preferences and misunderstanding of trial design. A central ethical and methodological requirement for running a randomised controlled trial is the presence of clinical equipoise. When equipoise exists, randomisation is ethically justified because no patient is knowingly given inferior treatment.

- Practical Challenges: Surgical RCTs are complex and costly due to small patient pools, blinding difficulties, technique variability, & equipoise concerns.

- Pragmatic Trials: Focus on real-world effectiveness, broad eligibility, and patient-centred outcomes like function or quality of life. Often preferred in surgery to increase generalisability and recruitment. In contrast to explanatory trials, which assess whether an intervention can work under idealised circumstances, a pragmatic trial asks whether an intervention does work when applied to the real world.

- Reporting Guidelines: Use the CONSORT statement to ensure trial reports are transparent, complete, and reproducible. Appraise trial quality with the Cochrane RoB 2 tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials.

Examples

Despite the inherent challenges of conducting surgical RCTs, several high-quality trials have been successfully delivered in plastic surgery, demonstrating that rigorous evidence is both achievable and essential for guiding clinical practice.

- NINJA Trial (Jain et al., 2023): Paediatric Hand Surgery

- Design: Pragmatic, multicentre (NHS hospitals).

- Focus: Replace vs. discard nail plate after nailbed repair.

- Findings: No difference in infection or cosmesis; discarding nails may save £720,000 annually.

- Impact: Informed widespread practice change for a common paediatric injury.

- MSLT Trials (Morton, Faries, Leiter) - Melanoma Surgery

- MSLT-I: Validated sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) as a staging tool.

- MSLT-II & DeCOG-SLT: Showed no survival benefit from completion lymphadenectomy in positive SLNB cases.

- Impact: Transformed global melanoma guidelines — SLNB became standard; routine completion lymphadenectomy was de-emphasised.

- WOLLF Trial (Costa et al., 2018) - Open Lower Limb Fractures

- Design: 24-centre UK trauma RCT.

- Focus: Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) vs. standard dressings.

- Findings: No significant difference in disability, infection, or quality of life.

- Impact: Shaped NICE guidance and NHS funding decisions for cost-effective wound care.

- SWIFFT Trial (Dias et al., 2020) - Scaphoid Fractures

- Design: 31-centre UK RCT.

- Focus: Early surgical fixation vs. cast for minimally displaced fractures.

- Findings: No functional difference; surgery had a higher complication rate (14% vs. 1%).

- Impact: Supports cast immobilisation as first-line, saving ~£1,295 per patient.

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

As plastic surgery literature expands, synthesising evidence through systematic reviews (SRs) and meta-analyses (MAs) has become essential for guiding practice and research. These methods inform clinical guidelines and help identify research gaps for future studies.

Types

- Systematic Reviews (SRs): Identify, appraise, and summarise all relevant studies using transparent, reproducible methods.

- Meta-Analysis (MA): Statistically combines results to improve power and precision when studies are sufficiently similar.

- Network Meta-Analysis (NMA): Allows comparison of multiple interventions, even without direct head-to-head trials.

Examples

- A meta-analysis directly informed national hand surgery guidelines and led to the HAWAII RCT on antimicrobial use.

- NMA has been used in areas like antibiotic prophylaxis and skin grafting techniques, where multiple treatment permutations limit direct comparisons.

Advantages and Limitations

- Plastic surgery often involves small, heterogeneous studies; MAs can overcome underpowered data and yield stronger conclusions.

- However, the strength of SRs and MAs depends on the quality of included studies. Researchers must assess: Risk of bias using validated tools, Statistical heterogeneity (e.g., I²), and publication bias.

- NMAs additionally require careful evaluation of transitivity and consistency assumptions.

Reporting and Quality Tools

- Use PRISMA guidelines for transparent reporting.

- Assess quality with AMSTAR 2: amstar.ca.

- Evaluate evidence certainty with GRADE: gradeworkinggroup.org or via Cochrane resources.

- For NMAs, use CINeMA: cinema.ispm.unibe.ch.

- Pre-register protocols on PROSPERO to enhance transparency and reduce duplication.

A minimum of 3 relevant studies are required to complete a meta-analysis. However, you should aim to include at least 5 high-quality studies to ensure sufficient power and validity of pooled results.

Patient-Centred Research Methods

In plastic surgery, clinical success alone is not enough. Factors like identity, satisfaction, and quality of life often define the true impact of a procedure. Two complementary approaches help capture these dimensions: qualitative research and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs).

Qualitative Research

Although still underused, qualitative research is gaining traction as plastic surgery shifts toward more patient-centred care. Understanding the why behind patient decisions is increasingly valued alongside measuring what was done.

- Purpose: Explores patient motivations, experiences, and perceptions, particularly relevant in cosmetic surgery, body image, and congenital conditions.

- Methods: Involves collecting non-numerical data through interviews, focus groups, or narratives, analysed using structured approaches like thematic analysis or grounded theory.

- Rigour: High-quality studies ensure transparency in sampling, data saturation, and reflexivity.

- Application: Often integrated into mixed-methods designs, providing crucial context to numerical outcomes. While these insights are rich and deeply informative, they may lack generalisability and require nuanced interpretation.

As the field evolves, qualitative research is essential for designing interventions that reflect what patients truly value — not just what can be measured.

Patient Reported Outcomes Measures (PROMS)

PROMs are now central to plastic surgery research and care, reflecting a shift toward measuring success from the patient’s perspective. They capture important outcomes that traditional clinical endpoints often miss.

- Purpose: Assess aspects of health that only patients can report, such as pain, function, satisfaction, and emotional well-being, especially relevant in reconstructive and aesthetic surgery.

- Tools: PROMs like the BREAST-Q, FACE-Q, CLEFT-Q, and BODY-Q are designed specifically for plastic surgery. They’re validated using psychometric methods such as Rasch analysis to ensure consistency and relevance.

- Innovation: AI-driven platforms like Computerised Adaptive Testing (CAT) and Ecological Momentary CAT (EMCAT) tailor question sets in real-time, reducing the burden while maintaining precision.

- Application: PROMs are widely used in trials, audits, and service evaluations. In the UK, programmes like NHS England’s GIRFT use PROM data to benchmark outcomes, identify variation, and support value-based care.

- Interpretation: PROM studies must distinguish between statistical and clinical significance. Reporting Minimal Important Difference (MID) and Minimal Detectable Change (MDC) helps determine whether observed changes are truly meaningful to patients.

As plastic surgery evolves, PROMs ensure we measure not just what was done, but how it improved patients’ lives.

Improving the Quality of Research

While research in plastic surgery has advanced, much of it remains fragmented, underpowered, or misaligned with real-world needs. Improving quality requires better infrastructure, collaboration, and alignment with patient and clinical priorities. Three key strategies are driving this shift.

Collaborative Research in Plastic Surgery

Collaborative research networks are transforming surgical research, particularly in plastic surgery, where single-centre studies often lack scale or generalisability.

- Purpose: By pooling data, expertise, and infrastructure, these networks enable large, multicentre projects that are otherwise unfeasible.

- Examples: The Reconstructive Surgery Trials Network (RSTN) and Plastic Surgery Trainee Collaborative (PSTC) in the UK have led high-quality prospective studies, RCTs, and audits. Their distributed leadership models promote trainee engagement, faster recruitment, and more inclusive authorship.

Collaboration improves study power, speeds up delivery, and fosters a culture of shared research across career stages.

Registries and Big Data

Registries provide a foundation for large-scale outcome tracking in plastic surgery. Combined with AI and machine learning, big data is being used to predict outcomes, guide decision-making, and personalise care.

- Purpose: Track long-term safety, performance, and efficacy, especially for implants and low-volume procedures.

- Examples: The UK National Flap Registry and ICOBRA support benchmarking, audit, and international quality improvement.

- Strengths and Limitations: Linking registries with PROMs and electronic records allows for deep, real-time analysis. Key challenges include data quality, completeness, and governance, solvable through good design and clinician engagement.

Collaborate with research methodologists early to refine study design and data collection strategies.

Research Priority Setting Partnerships

PSPs reduce research waste by aligning funding and effort with genuine clinical uncertainty. They increase transparency, inclusivity, and relevance, strengthening the evidence base where it matters most.

Many studies still focus on questions with limited relevance or impact. Priority-setting partnerships (PSPs) aim to correct this by identifying questions that matter most to patients and clinicians.

- How it works: The James Lind Alliance (JLA) brings together stakeholders to reach consensus on research priorities through structured, inclusive processes.

- Examples

- Global Burns PSP: Identified top priorities like infection, scarring, skin regeneration, and first aid in low-resource settings.

- Hand & Wrist PSP (BSSH): Highlighted uncertainties around peripheral nerve compression, arthritis, scar management, and PROM use.