Summary Card

Overview

Sutures are medical threads and needles used to approximate tissues and facilitate healing. Their properties: material, structure, absorbability, and diameter, determine how they behave in tissue and influence scar quality and infection risk.

Material

Sutures are classified by material and filament structure. Monofilament sutures glide smoothly through tissue but have more “memory,” while multifilament sutures handle better but harbour bacteria.

Structure & Coating of Sutures

Monofilament sutures are single strands with low tissue drag and lower infection risk but have high memory and require secure knots. Multifilament sutures are braided or twisted, offering superior handling and knot security but increased tissue drag and bacterial colonisation.

Absorbability

Absorbable sutures lose most of their tensile strength over weeks to months and are used for deep or temporary closure. Non‑absorbable sutures maintain strength for months or years.

Common Suture Types & Their Uses

Vicryl is a braided absorbable for deep and subcuticular closures; Monocryl is a smooth absorbable for skin; PDS provides long‑term support; Nylon and Prolene are inert monofilaments for skin; Silk offers excellent handling but high tissue reactivity.

Sizing System

The USP scale labels sutures by diameter; more zeroes indicate a smaller suture (e.g., 6‑0 is finer than 3‑0). Larger sizes (#0–10) are used for fascia or strong tissues, while small sizes (4‑0 to 7‑0) are used for skin and delicate structures.

Suture Needles

A suture needle comprises a swage, body, and point, and is selected according to tissue type and access. Cutting needles are used for skin, taper needles for soft tissue, and curved needles.

Clinical Selection & Removal

Choose sutures based on tissue biology, healing timeline. and contamination risk. Use absorbable monofilaments for deep closures, non‑absorbable monofilaments for skin, and avoid multifilaments in contaminated wounds.

Verified by thePlasticsFella ✅

Overview of Suture Types & Sizes

Sutures are medical threads and needles used to approximate tissues and facilitate healing. Their properties: material, structure, absorbability, and diameter, determine how they behave in tissue and influence scar quality and infection risk.

Suturing remains the mainstay of wound closure in plastic and reconstructive surgery. Although alternatives such as staples and tissue adhesives exist, sutures provide versatility, control, and strength across a wide range of tissues. No single suture is perfect and the surgeon’s challenge is to understand the available options and match them to the biological and mechanical requirements of each wound.

This article summarises the classification of sutures, common materials used in plastic surgery, the USP sizing system, needle designs, and practical guidelines for choosing and removing sutures.

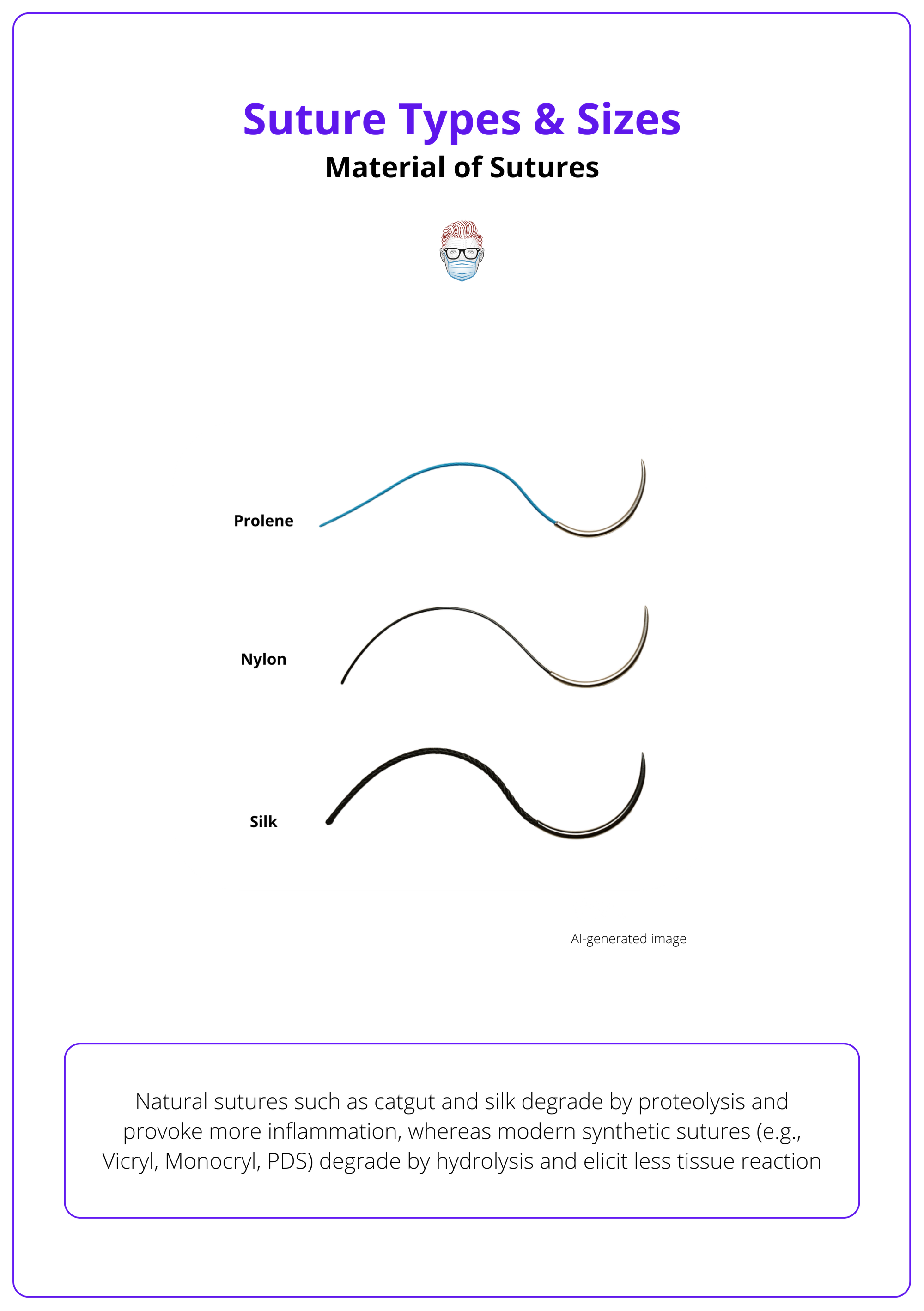

Material of Sutures: Natural vs Synthetic

Natural sutures such as catgut and silk degrade by proteolysis and provoke more inflammation, whereas modern synthetic sutures (e.g., Vicryl, Monocryl, PDS) degrade by hydrolysis and elicit less tissue reaction

Suture material influences tensile strength, absorption and immune response. Historically, surgeons relied on natural fibres like gut and silk, but these incite significant inflammation and unpredictable absorption. Synthetic polymers now dominate because they offer predictable degradation and minimal immunogenicity.

- Catgut: Twisted collagen from sheep or bovine intestine; absorbs rapidly via proteolysis; significant tissue reaction; used for mucosal closures and rapidly healing tissues.

- Silk: Natural braided fibre; technically non‑absorbable but loses strength over about one year; superb handling and knot security; high tissue reactivity; mainly used to secure drains or retract tissues.

- Synthetic Absorbable: Vicryl (braided polyglactin 910) retains strength for 2-3 weeks and is fully absorbed within 8-10 weeks. Monocryl (monofilament poliglecaprone 25) loses 50 % strength within a week and disappears by 120 days. PDS (monofilament polydioxanone) provides long‑term support for 4-6 months.

- Synthetic Non‑Absorbable: Nylon (monofilament polyamide) retains strength for years and has very low tissue reactivity but high memory. Polypropylene (Prolene/ProNova) is inert, non‑degradable, and widely used for skin and vascular sutures. Polyester (Ethibond) is strong and pliable but braided, so infection risk is higher.

The suture types based on material are illustrated below.

Structure & Coating of Sutures

Monofilament sutures are single strands with low tissue drag and lower infection risk but have high memory and require more secure knots. Multifilament sutures are braided or twisted, offering superior handling and knot security but increased tissue drag and bacterial colonisation.

Filament structure affects how a suture handles and how tissues respond. Coating can reduce friction or deliver antibacterial agents.

- Monofilament: Smooth passage through tissues; minimal capillarity; high memory; examples include PDS, Monocryl, Prolene, and Nylon.

- Multifilament: Braided or twisted strands; better flexibility and knot security; higher friction and capillarity; examples include Vicryl, Silk, and Polyester.

- Coated & Barbed: Braided sutures such as Vicryl may be coated with polymer or wax to reduce drag. Antibacterial coatings (e.g., triclosan in Vicryl Plus) lower infection rates. Barbed sutures (e.g., Stratafix) have small hooks that anchor tissue and obviate the need for knots.

- Alternatives & Adhesives: Tissue adhesives (cyanoacrylate glues) and surgical strips can serve as adjuncts or alternatives to sutures for superficial wounds. Adhesives provide rapid closure, eliminate knot tying, and yield excellent cosmetic outcomes, but they lack tensile strength and are reserved for small, low‑tension incisions. Surgical strips (steri‑strips) are often applied after suture removal to support skin edges during maturation.

Absorbability of Sutures

Absorbable sutures lose tensile strength over weeks to months, making them suitable for internal tissues that heal quickly. Non‑absorbable sutures retain strength long term and are removed when used on skin or left in place when buried.

Absorbable sutures are degraded by the body and obviate the need for removal. Natural absorbables like catgut degrade by proteolysis and provoke more inflammation, while synthetic absorbables degrade by hydrolysis and are less reactive. Non‑absorbable sutures may remain permanently or be removed after healing.

- Absorbable (Natural): Catgut and chromic gut absorb within weeks; high variability and inflammation; limited use today.

- Absorbable (Synthetic): Vicryl, Monocryl, and PDS. Vicryl provides moderate support and is widely used for muscle and skin closure. Monocryl is smooth with rapid absorption and minimal tissue reaction. PDS retains strength for 4–6 months and is used for fascial closures.

- Non‑Absorbable: Nylon and Polypropylene are inert monofilaments used for skin closure, vascular, and nerve repair. Silk and Polyester are braided and used for ligatures, tendon repairs, and sternal closures.

Common Suture Types & Their Uses

Familiarity with common suture brands helps match properties to clinical needs. Vicryl is a braided absorbable for deep and subcuticular closures; Monocryl is a smooth absorbable for skin; PDS provides long‑term support; Nylon and Prolene are inert monofilaments for skin; Silk offers excellent handling but high tissue reactivity.

The typical properties and uses of frequently employed sutures are summarised below.

- Vicryl (Polyglactin 910): Braided, absorbable; retains strength for 2-3 weeks; fully absorbed by 8-10 weeks; moderate tissue reaction; used for muscle, subcuticular, and pediatric skin closure.

- Monocryl (Poliglecaprone 25): Absorbable monofilament; loses 50 % strength by 1 week and disappears by 120 days; very smooth with minimal reactivity; ideal for intradermal and facial sutures.

- PDS (Polydioxanone): Absorbable monofilament; retains strength for 4-6 months; high memory; used for fascia, tendons, and gastrointestinal anastomoses.

- Nylon (Ethilon): Non‑absorbable monofilament; strong with minimal reactivity but high memory; used for interrupted skin sutures, nerve, and microvascular repairs.

- Polypropylene (Prolene/ProNova): Non‑absorbable monofilament; inert and permanently strong; used for skin closure, vascular anastomoses, and abdominal wall reinforcement.

- Silk: Braided natural fibre; excellent handling but high tissue reaction; loses strength over one year; used to secure drains or as stay sutures.

- Polyester (Ethibond): Braided synthetic; very strong and durable; minimal tissue reaction; used in tendon repairs, sternotomy closure, and orthopaedic fixation.

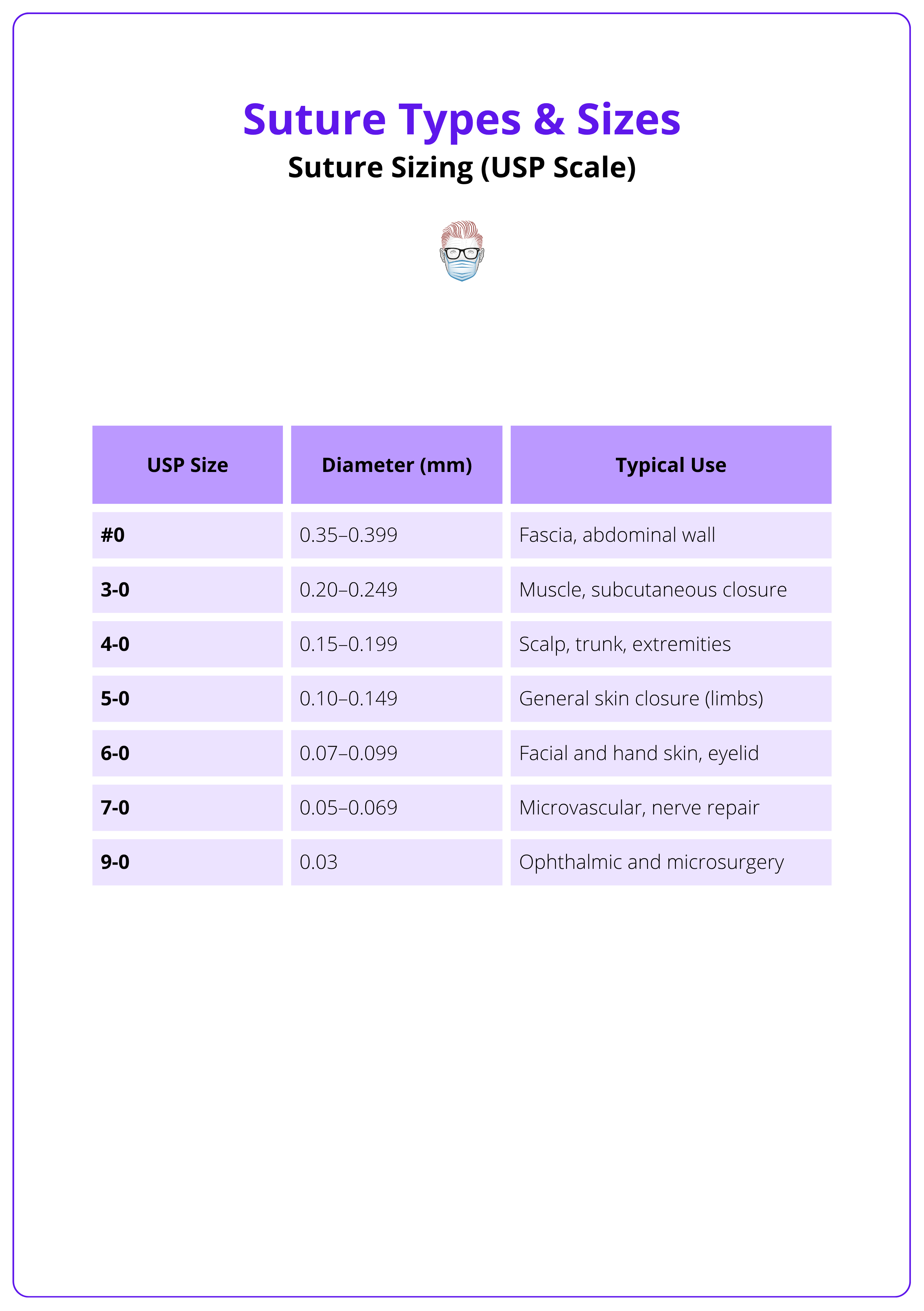

Suture Sizing (USP Scale)

The United States Pharmacopeia's (USP) system ranks sutures by diameter: larger numbers (#1-10) are thicker, whereas more zeros denote finer sutures (2‑0 to 12‑0). Adjacent sizes differ by about 0.01-0.05 mm.

Suture size impacts tensile strength and scar visibility. Thicker sutures are stronger but leave larger needle holes; finer sutures are less visible but break more easily. The table below summarises typical sizes and uses. Choose a size that balances strength and cosmesis. For example, 3‑0 for muscle and 6‑0 for facial skin.

The USP scale is summarised below.

Suture Needles

A suture needle comprises a swage, body and point, and is selected according to tissue type and access. Cutting needles (conventional or reverse) are used for skin, taper needles for soft tissue, and curved needles — most commonly 3/8 circles to provide optimal control.

Needles are manufactured with the suture swaged to the end, eliminating the bulk of an eye and reducing tissue trauma. The body dictates curvature; the point dictates penetration. Selecting the right combination ensures efficient passage through tissue and minimal damage.

Components

- Swage: Connection between needle and suture; modern needles are swaged rather than eyed, creating a smooth transition.

- Body & Curvature: Curved needles are specified by the fraction of a circle — 1/4, 3/8, 1/2, and 5/8. A 3/8‑circle needle is versatile for most skin closures; a 1/2‑circle needle is useful in confined spaces such as the oral cavity.

- Point: Cutting needles have a triangular tip; conventional cutting needles slice toward the wound edge, while reverse cutting needles protect the wound edge and are preferred for skin. Taper needles have a round tip that spreads tissue and are used for muscle, bowel, and vessels. Blunt and spatula needles are used for friable tissues and ophthalmic surgery respectively.

Clinical Selection & Removal of Sutures

Suture choice depends on tissue type, healing time, and infection risk. Use absorbable sutures for internal tissues, monofilaments in contaminated wounds, and select appropriate sizes for strength and cosmesis. Remove skin sutures at 3-14 days, depending on location.

Matching suture properties to clinical circumstances optimises healing and minimises complications. In contaminated or high‑risk wounds, avoid braided sutures because bacteria harbour in interstices. Absorbable monofilaments are ideal for deep layers or when patients may not return for removal, while non‑absorbable monofilaments are used for skin where removal is planned. Removal timing hinges on location: remove facial sutures after 3-5 days; scalp, arms, and hands after 7-10 days; trunk and legs after 10-14 days.

Guidelines for Suture Selection

- Tissue & Healing: Use absorbable sutures (Vicryl, Monocryl) for mucosa and subcutaneous layers; use durable sutures (PDS) for fascia and tendons; use non‑absorbable monofilaments (Prolene, Nylon) for skin and vascular repairs.

- Contamination: Choose monofilament sutures in contaminated or infection-prone sites; avoid braided sutures like Silk or Vicryl in these settings.

- Cosmetic Sites: Use fine monofilament sutures (5‑0 to 7‑0) or subcuticular absorbable sutures for the face and hand to minimise scarring.

- High‑Tension Areas: Use stronger sutures (2‑0 to 3‑0) for knees, elbows, and abdomen where tension is high; consider buried absorbable sutures with a second layer of non‑absorbables for added support.

- Removal Timing: Follow region‑specific removal guidelines: face 3-5 days; scalp and arms 7-10 days; trunk, back, and legs 10-14 days.

Conclusion

1. Understand Material Differences: Recognise that natural sutures (catgut, silk) degrade by proteolysis and incite more inflammation, whereas synthetic sutures (Vicryl, Monocryl, PDS, Nylon, Prolene) degrade by hydrolysis or do not degrade and are now preferred.

2. Distinguish Filament Structures: Differentiate between monofilament sutures, which reduce infection risk but have high memory and braided multifilaments, which handle better but harbour bacteria.

3. Select by Absorbability: Match absorbable sutures to tissues that heal quickly and non‑absorbable sutures to tissues requiring prolonged support or planned removal.

4. Choose Appropriate Sizes & Needles: Use the USP scale to select suture diameter based on tissue strength and cosmesis, and select needle curvature and point type to suit tissue characteristics.

5. Apply Clinical Guidelines: Choose sutures based on tissue, infection risk, and cosmetic needs, and remove them according to body region (3-14 days).

Further Reading

- Rose, J. & Tuma, F. (2023) Sutures and Needles. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing

- Khan, A.Z., Tønseth, K.A., Koidl, A. & Utheim, T.P. (2023) ‘Suture materials’, Tidsskrift for Den norske legeforening, 143. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.22.0708.

- Lippincott Procedures (2024) Skin suture removal, ambulatory care. Revised 19 February 2024. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer.

- Watson, L.J. (2015). Types of suture material. Geeky Medics, 5 February.

- Mathes, S.J. & Nahai, F. (1997). Reconstructive surgery: principles, anatomy, and technique. New York: Churchill Livingstone.