Summary Card

Overview

Suturing techniques are tailored to wound characteristics. Understanding when to choose each method and how to execute it safely ensures secure closures and minimizes complications.

Simple Interrupted Sutures

Simple interrupted sutures are the work‑horse of wound closure. Each stitch provides strong closure and can be individually removed, making this technique versatile and safe for many wounds.

Horizontal Mattress Sutures

The horizontal mattress suture distributes tension across a wound and provides efficient edge eversion, making it useful for fragile skin. However, mismatched bites can lead to edge misalignment, and exposed sutures increase infection risk.

Deep Dermal Interrupted Sutures

Deep dermal sutures relieve tension on the skin edges by approximating the dermis and hypodermis. They bury the knot within the wound, providing structural support.

Subcuticular Continuous Sutures

Subcuticular continuous sutures run within the dermis to create an almost invisible closure with excellent cosmetic results. They provide minimal tensile strength on their own and must be supported by deep sutures in high‑tension wounds.

Vertical Mattress Sutures

Vertical mattress sutures combine a far‑far bite with a near‑near bite to achieve robust closure and edge eversion. They are particularly useful in high‑tension areas but require meticulous technique and may cause tissue necrosis or scarring if tied too tightly.

How to Tie a Surgeon’s (Triple) Knot

The surgeon’s knot is a variation of the square knot with a double first throw for added friction and security. It is used when wound tension is high or tissues are prone to separation; secure knots prevent dehiscence.

Verified by thePlasticsFella ✅

Overview of Suturing & Knot Tying

Suturing techniques are tailored to wound characteristics. Understanding when to choose each method and how to execute it safely ensures secure closures and minimizes complications.

Proper wound closure is fundamental in surgical practice. In plastic surgery and trauma care, the surgeon selects a technique based on wound tension, skin thickness, cosmesis, and location.

Interrupted sutures are versatile and allow individual removal if infection occurs. Mattress sutures (horizontal or vertical) distribute tension across wider bites and help evert edges, but they can cause tissue strangulation if overtightened or if bites are unequal. Deep dermal sutures provide internal support and reduce dead space; they must be combined with superficial closure for optimal skin alignment. Subcuticular continuous sutures hide the suture line to provide a superior cosmetic result.

Finally, the knot tying technique, particularly the surgeon’s knot with its double first throw, ensures knot security when tension is high.

Match Suture Size and Material: Select appropriate suture (monofilament or braided, absorbable or non‑absorbable) based on tissue type and required support duration; absorbable monofilaments generate less inflammation but may provide shorter support.

Simple Interrupted Sutures

Simple interrupted sutures are the work‑horse of wound closure. Each stitch provides strong closure and can be individually removed, making this technique versatile and safe for many wounds.

The simple interrupted technique is suitable for wounds with well‑approximated edges under little tension. Each suture is placed separately, allowing removal of one or more stitches without compromising the rest of the closure if there is infection or dehiscence. This independence improves safety but increases the number of knots and time needed. Proper placement with equal distance from the edge and equal depth ensures wound eversion and minimizes step‑off.

Technique (out‑to‑in and in‑to‑out)

- Insertion: Gently lift the skin edge with forceps; insert the needle perpendicular (90°) to the skin about 4 mm from the wound edge and drive it through the dermis.

- Pass: Follow the curvature of the needle through the tissue until it emerges in the middle of the wound. Use the forceps to re‑grasp the needle for precision.

- Re‑entry: On the opposite side, lift the skin and insert the needle from inside to outside at an equal distance (~4 mm) and depth.

- Tie: Pull the suture through, leaving approximately 3 cm of tail. Tie a secure square or surgeon’s knot, then trim the ends to about 5–6 mm to avoid unravelling.

- Advantages

- Allows individual removal of stitches; useful if part of the wound becomes infected.

- Provides strong closure with good control of edge approximation.

- Versatile for many body sites and wound shapes.

- Limitations

- Time‑consuming due to multiple knots.

- Numerous external knots may harbor bacteria and increase infection risk.

- Less effective in high‑tension areas without additional deep sutures.

Avoid overtightening; excessive tension can strangulate tissue, leading to necrosis and widened scars.

Horizontal Mattress Sutures

The horizontal mattress suture distributes tension across a wound and provides efficient edge eversion, making it useful for fragile skin. However, mismatched bites can lead to edge misalignment, and exposed sutures increase infection risk.

Horizontal mattress sutures are placed in two bites on each side of the wound in a transverse orientation. They spread tension along the wound edges, making them ideal for friable or thin tissue that might tear with standard interrupted sutures. Because the loop of suture sits outside the skin, removal is straightforward, but prolonged exposure may cause cross‑hatching scars or infection; early removal is recommended in cosmetic areas.

Technique

- Insert: Enter the skin 4-8 mm from the wound edge and exit on the opposite side.

- Mirror: Move laterally 3-5 mm along the wound; re‑enter the far side and bring the needle back to the original side at the same distance and depth.

- Secure: Tie the knot lateral to the wound so the external loop lies flat across the incision. Avoid overtightening to prevent strangulation and tissue necrosis.

- Advantages

- Provides excellent edge eversion and distributes tension across a larger area.

- Useful in fragile or thin skin and for controlling hemostasis.

- Limitations

- External loops may leave cross‑hatched scars; should be removed within a few days in cosmetic areas.

- If bites are unequal, edges may misalign, causing a stepped scar.

- Increased risk of infection due to more suture material exposed externally.

Deep Dermal Interrupted Sutures

Deep dermal sutures relieve tension on the skin edges by approximating the dermis and hypodermis. They bury the knot within the wound, providing structural support.

These buried stitches begin and end at the wound base, inverting the knot under the dermal plane. Their primary role is to close dead space and reduce tension on superficial sutures. Deep dermal sutures are indicated for deep wounds under tension, areas prone to keloids, and wounds with dead space. They are contraindicated in severely contaminated wounds or when the dermis is too thin to support the knot.

Technique

- Prepare: After cleansing and draping, insert the needle into the dermis at the bottom of the wound and direct it upward, exiting near the dermal‑epidermal junction on the same side.

- Cross: Insert the needle on the opposite side near the dermal‑epidermal junction, directly across from the exit point; take small bites to avoid puckering.

- Tie and bury: Exit at the same dermal plane and tie the knot using a few throws; bury the knot under the dermis, leaving a 3‑mm tail to prevent knot unraveling.

- Finish: If needed for accurate skin approximation, add a superficial running or interrupted closure after the deep sutures.

- Advantages

- Reduces tension on the skin surface, decreasing the risk of widened scars or dehiscence.

- Buried knot avoids external suture marks and reduces infection risk.

- Helps obliterate dead space in deep wounds.

- Limitations

- Technically more challenging, particularly in areas with thin dermis.

- Requires additional superficial closure for proper epidermal alignment.

- Should be avoided in contaminated wounds; may increase infection risk in dirty fields.

Layered closure involves using deep dermal sutures before superficial closure to relieve tension in thick skin or high‑stress areas; finish with a subcuticular stitch for optimal cosmesis when appropriate.

Subcuticular Continuous Sutures

Subcuticular continuous sutures run within the dermis to create an almost invisible closure with excellent cosmetic results. They provide minimal tensile strength on their own and must be supported by deep sutures in high‑tension wounds.

This technique involves a continuous intradermal suture that lies beneath the epidermis. It is ideal for straight, low‑tension wounds, particularly on the face or areas where cosmetic outcome is paramount. Because the suture is hidden, there are no external stitches to remove. The method relies on proper tension, equal spacing, and avoiding full‑thickness bites, which could lead to “railroad track” scars or dehiscence.

Technique

- Anchor: Start with a buried knot at the apex of the wound by taking a deep‑dermal bite and tying the suture. This anchors the continuous stitch.

- Insert: Bring the needle out at the dermo‑epidermal junction; this ensures the suture lies within the dermis.

- Pass: Progress with small, alternating intradermal bites (2-3 mm) in an S‑shaped pattern along the wound, keeping bites parallel to the skin surface.

- Finish: At the end of the wound, secure the suture with an Aberdeen knot or loop knot; bury the tail beneath the skin and cut flush.

- Advantages

- Provides excellent cosmetic results with no external suture marks.

- Avoids the need for suture removal; well‑tolerated by patients.

- Minimal inflammatory response when absorbable monofilament is used.

Limitations

- Offers limited tensile strength; must be combined with deep sutures to prevent dehiscence.

- Technique‑sensitive; inconsistent spacing or excessive tension can cause poor cosmetic outcomes or tissue ischemia.

- Less suitable for curved or irregular wounds.

Reload the needle after each pass to maintain accurate bite spacing; consistent spacing and depth are key for a neat closure.

Vertical Mattress Sutures

Vertical mattress sutures combine a far‑far bite with a near‑near bite to achieve robust closure and edge eversion. They are particularly useful in high‑tension areas but require meticulous technique and may cause tissue necrosis or scarring if tied too tightly.

The vertical mattress suture incorporates two pairs of bites at different distances from the wound edge. The first (far‑far) bite takes a deep, wide pass that secures underlying tissues. The second (near‑near) bite takes a shallower pass close to the wound edge for eversion. This technique is valuable in deep wounds under tension but is more time‑consuming and may create cross‑hatched scars; it is less commonly used in cosmetic areas.

Technique

- Far‑far (first bite): Insert the needle 8 mm from the wound edge, pass it deep across the wound, and exit on the opposite side also 8 mm from the edge.

- Far‑far mirror: Reinsert on the far side and exit back to the original side at the same depth and distance.

- Near‑near (second bite): Reverse the needle; insert it 2 mm from the wound edge on the original side at half the depth, then exit on the opposite side at an equal distance.

- Tie: Gently tighten the suture to evert edges; tie a knot, ensuring not to constrict tissue.

- Advantages

- Provides strong closure and excellent edge eversion in high‑tension areas.

- Distributes tension across deeper tissues, reducing superficial scarring.

- Limitations

- Time‑consuming and technically demanding; not routinely used in plastic surgery.

- If tied too tightly, can cause tissue necrosis or noticeable cross‑hatched scars.

- External loops must be removed promptly to avoid marks.

Edge Eversion: Maintain slight eversion of wound edges; flat or inverted closure can result in depressed scars. Mattress sutures are useful for eversion but may need early removal to avoid scar marks.

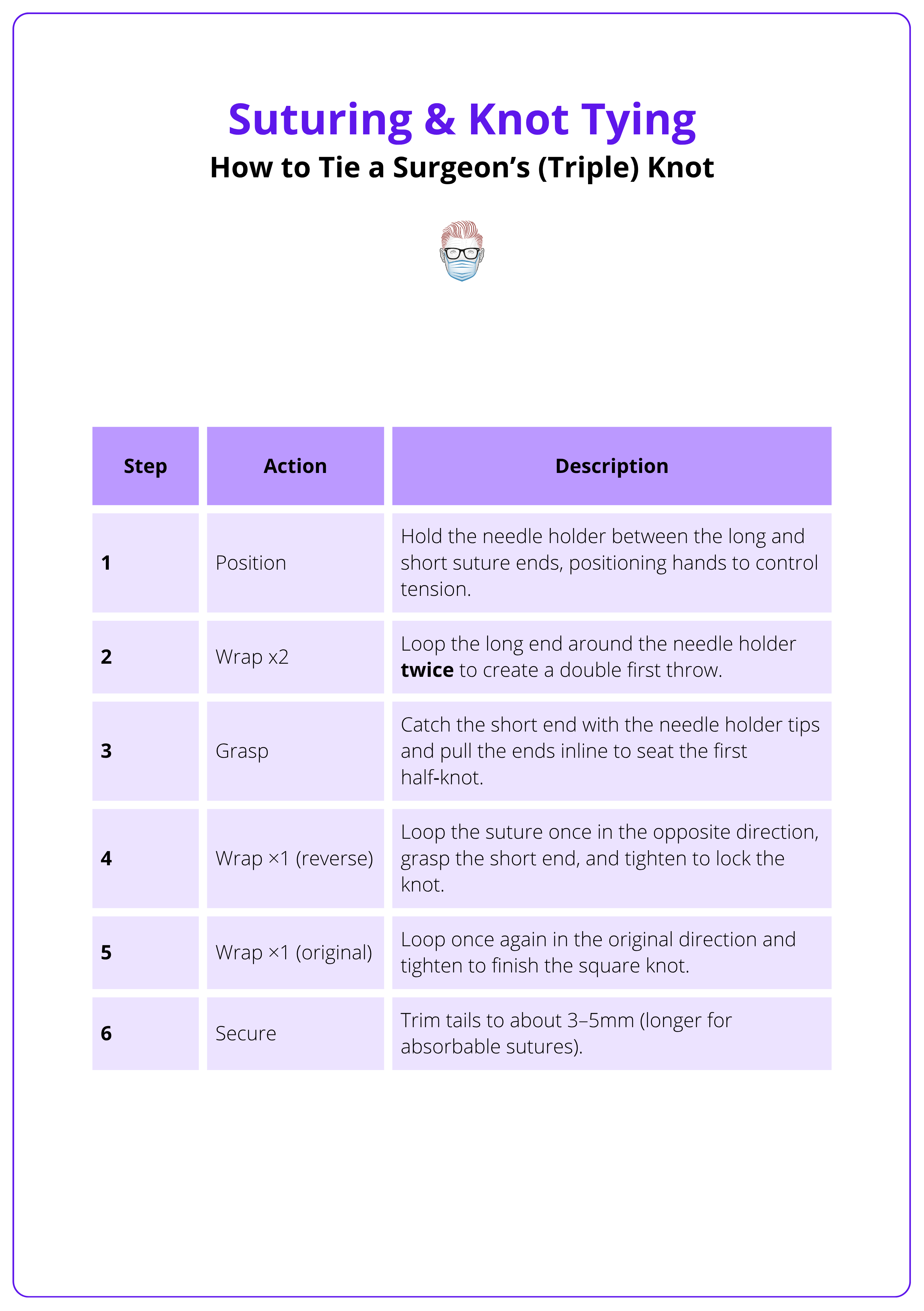

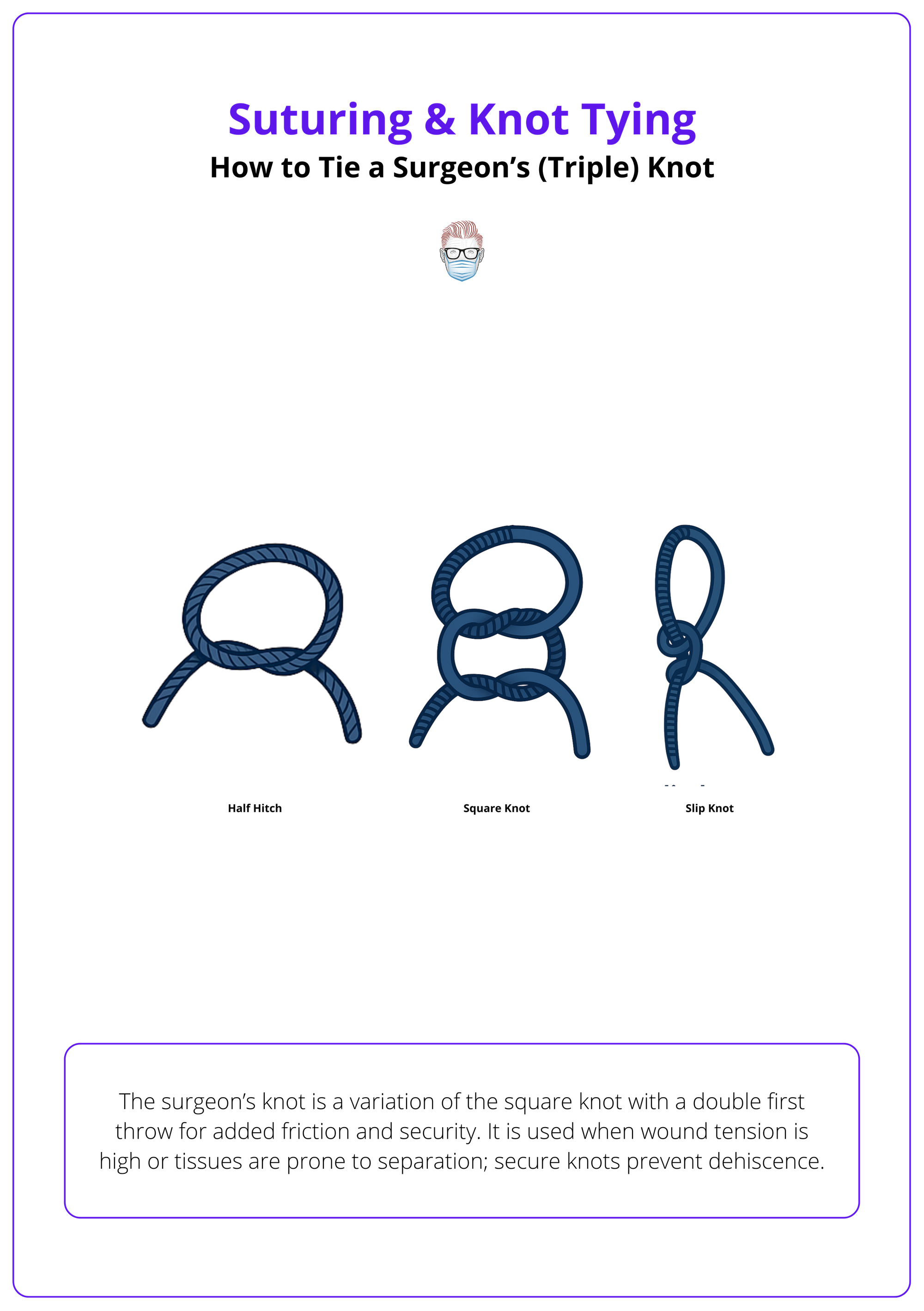

How to Tie a Surgeon’s (Triple) Knot

The surgeon’s knot is a variation of the square knot with a double first throw for added friction and security. It is used when wound tension is high or tissues are prone to separation; secure knots prevent dehiscence.

A surgeon’s (triple) knot provides increased friction in the first throw by looping the long end twice around the needle holder. This helps maintain tension during subsequent throws. While the term “triple knot” sometimes implies three throws in the first hitch, most surgical practice uses two loops for the first throw followed by two single throws to secure the knot. Excessive throws can bulk up the knot and may compromise closure.

Steps of Tying a Surgeon's Knot

A surgeon's knot-tying technique is illustrated below.

Always maintain tension along the line of the wound; avoid twisting the knot, which can create a slip knot. Practice with rope or larger sutures before progressing to fine materials.

Conclusion

1. Technique Selection: Each suture method has specific indications, advantages, and pitfalls. Matching the technique to the wound type ensures optimal closure and cosmetic outcome.

2. Key Steps: Proper needle placement (perpendicular entry at appropriate distance), equal bites, and secure knot tying (double loop for surgeon’s knot) are fundamental for strong closures.

3. Layered Approach: Combining deep dermal sutures for tension relief with subcuticular continuous sutures for cosmesis results in durable and aesthetic wound repair.

4. Risk Management: Avoid overtightening and misaligned bites to prevent tissue necrosis, scarring, or dehiscence.

5. Continual Practice: Practicing knot tying and suturing on models enhances precision and speed, reducing operative time and improving patient outcomes.

Further Reading

- Zuber, T.J. (2002) The mattress sutures: vertical, horizontal, and corner stitch. American Family Physician, 66(12), pp. 2231–2236.

- Streitz, M.J. (2023) How to do plastic surgical repair with buried deep dermal sutures. MSD Manual - Professional Version. Reviewed by Birnbaumer, D.M.

- Medico (n.d.) Continuous subcuticular suture technique.

- Brewster, C. and Anderson, I. (2017) Simple interrupted suture - OSCE guide. Geeky Medics, 29 July.

- University of Washington (2025) Knot tying: two-handed tie. UW General Surgery Technical and Professional Skills.