Summary Card

Overview

TEN is a severe dermatologic condition involving >30% TBSA, characterized by extensive skin and mucosal detachment, with high morbidity and mortality.

Pathophysiology

TEN is a drug-triggered, T-cell-mediated type IV hypersensitivity reaction that leads to widespread keratinocyte apoptosis and full-thickness epidermal necrosis.

Risk Factors

Drug-induced cases dominate, with triggers like antibiotics, antiepileptics, NSAIDs, and allopurinol. Risk factors include genetic predisposition, HIV, and polypharmacy.

Clinical Features

TEN presents with fever, malaise, painful erythematous macules, blisters, and mucosal erosions, often leading to multiorgan dysfunction.

Differential Diagnosis

Conditions mimicking TEN, such as SSSS and drug-induced linear IgA dermatosis, must be excluded to guide treatment.

Management

Focuses on discontinuing causative drugs, supportive care, fluid replacement, and wound care, with adjunct therapies like IVIG and cyclosporine as potential options.

Primary Contributor: Dr Kurt Lee Chircop, Educational Fellow

Verified by thePlasticsFella ✅

Overview of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

TEN is a life-threatening dermatologic emergency characterized by widespread epidermal and mucosal detachment, with high morbidity and mortality.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) and Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) are immunologically driven conditions on the same disease spectrum. Both result from keratinocyte apoptosis, typically triggered by medications.

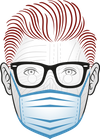

The extent of skin detachment (TBSA) defines severity and guides classification (Harris, 2016; Schwartz, 2013). This is explained in the table below.

Erythema Multiforme Major is no longer considered part of this spectrum, as it has a distinct pathogenesis.

Despite sharing the same underlying mechanism, TEN is far deadlier than SJS due to greater skin loss and systemic complications.

SJS and TEN share the same pathological process, but TEN has a higher mortality (25–50%).

Pathophysiology of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

TEN is a drug-triggered, T-cell-mediated type IV hypersensitivity reaction that leads to widespread keratinocyte apoptosis and full-thickness epidermal necrosis.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis results from an immune-mediated cytotoxic assault on the skin, triggered primarily by certain medications. The process is orchestrated by activated T lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cells, leading to massive epidermal cell death and skin detachment. Despite understanding the key pathways, the precise mechanism by which specific drugs initiate this cascade remains unclear.

Immune Mechanisms

TEN is driven by cytotoxic immune cells that directly induce keratinocyte death.

- Granulysin: A major mediator released by CD8+ T cells and NK cells that causes direct keratinocyte apoptosis.

- Perforin/Granzyme B: Cytotoxic proteins released by CD8+ T cells that enter target cells and trigger programmed cell death.

- Fas–Fas Ligand Interaction: Fas ligand on immune cells binds to Fas receptors on keratinocytes, initiating extrinsic apoptosis (Pereira, 2007; Kinoshita, 2016).

Apoptosis Pathways

Keratinocyte apoptosis in TEN occurs via intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms.

- Intrinsic Pathway: Triggered by mitochondrial damage and oxidative stress, leading to caspase activation.

- Extrinsic Pathway: Involves death receptors (e.g., Fas, TNF-α) on keratinocytes initiating apoptosis via downstream signaling cascades (Kinoshita, 2016).

Histopathology

Microscopic analysis reveals hallmark features of epidermal destruction.

- Full-Thickness Epidermal Necrosis: A defining histological feature of TEN.

- Subepidermal Blistering: Separation between dermis and epidermis due to extensive cell death.

- Minimal Dermal Inflammation: Despite severe epidermal damage, the dermis typically shows sparse inflammatory infiltrates (Harris, 2016).

TEN is initiated by immune activation, primarily CD8+ T cells and NK cells, which target keratinocytes through direct cytotoxic mechanisms. The resulting cell death leads to rapid epidermal detachment and mucocutaneous injury.

The exact mechanism by which the triggering agent activates the proposed pathways remains unclear.

Risk Factors of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Drug-induced cases dominate, triggered within the first 8 weeks of therapy. Genetic predisposition, comorbidities, and polypharmacy amplify risk.

TEN is most often drug-induced, with causative agents typically identified within 1-3 weeks of initiating therapy. Non-drug causes are rare but significant, especially in children.

Drug Causes

- Antibiotics: Sulfonamides, macrolides, penicillins, quinolones.

- Antiepileptics: Phenytoin, carbamazepine, lamotrigine.

- NSAIDs: Oxicam derivatives.

- Allopurinol: Common in gout management.

Non-Drug Causes

- Viral infections (e.g., herpes, Mycoplasma pneumoniae).

- Post-vaccination reactions.

- Organ transplantation.

Risk Factors

- Genetic Predisposition: HLA-B1502 and HLA-A3101 (high prevalence in Southeast Asians).

- Medical Conditions: HIV, autoimmune diseases, malignancies.

- Polypharmacy: Increases difficulty in identifying causative agents.

A causal link is often established when TEN occurs 1-3 weeks after starting a new medication.

Clinical Features of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

TEN begins with flu-like symptoms and rapidly progresses to painful skin detachment, mucosal erosions, and systemic involvement, often resulting in multi-organ failure.

TEN presents with a distinct progression: a short prodromal phase followed by extensive cutaneous and mucosal damage, with high risk for sepsis and organ dysfunction. Prompt recognition of these signs is critical for early diagnosis and supportive care.

Prodromal Phase

Fever, malaise, sore throat, cough, myalgia, and arthralgia typically appear 1–3 days before skin involvement (Schwartz, 2013).

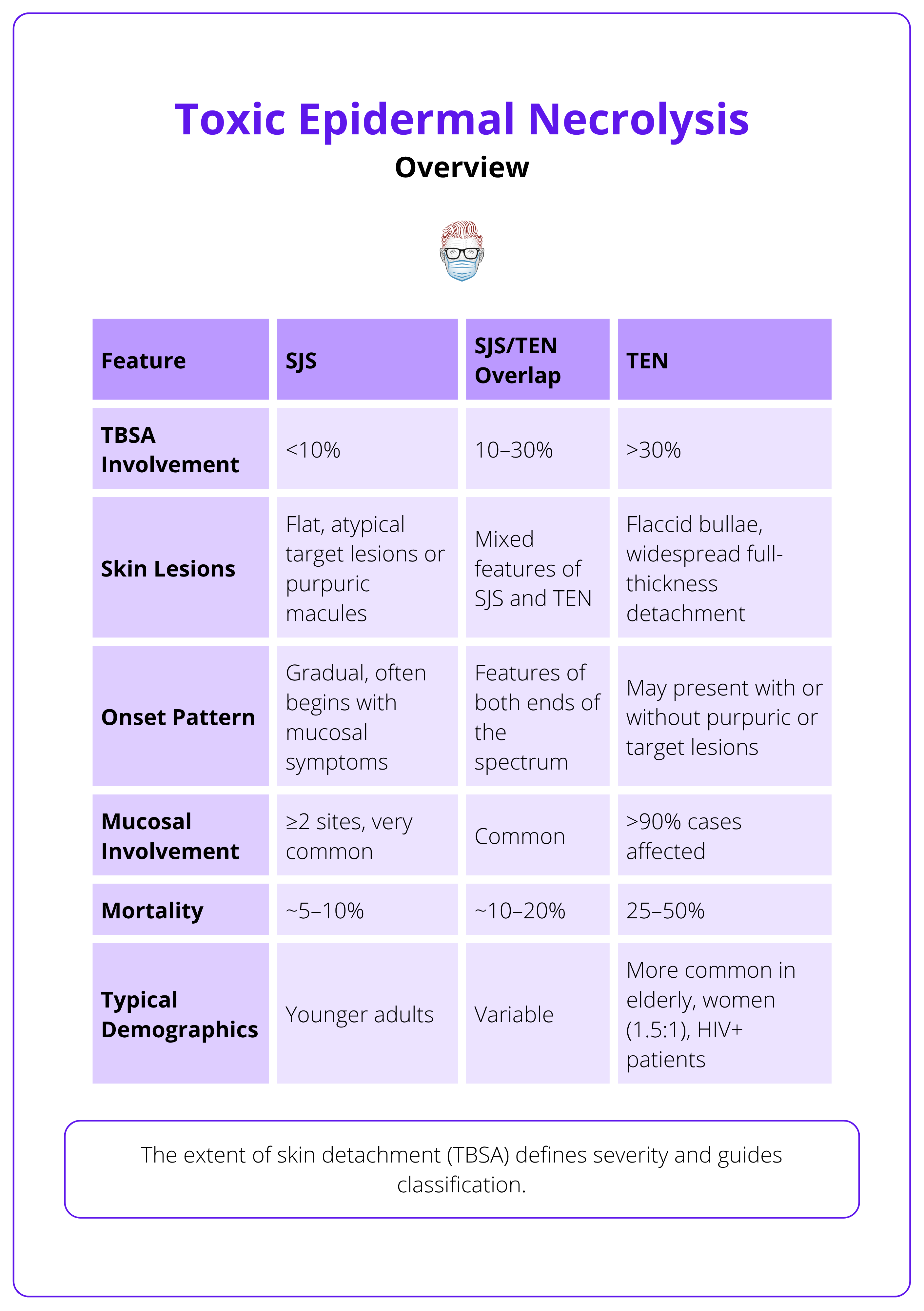

Cutaneous Findings

- Pain: Severe skin pain often precedes visible blistering and is initially out of proportion to skin findings (Pereira, 2007).

- Macules: Painful erythematous macules with purpuric centers, starting on the face and trunk.

- Bullae: Lesions coalesce into flaccid bullae and large sheets of epidermal detachment (>30% TBSA).

- Nikolsky’s sign: Positive (epidermal sloughing with gentle pressure) (Gerull, 2011).

Mucosal Involvement (>90% of cases)

- Oral/lips: Cheilitis, painful ulcers, stomatitis.

- Eyes: Conjunctivitis, corneal ulcers, anterior uveitis.

- Genital/urinary tract: Erosions, ulcers, dysuria, urinary retention.

- Respiratory tract: Tracheobronchial erosions causing cough, respiratory distress.

- Gastrointestinal tract: Diarrhoea and mucosal damage.

Systemic Manifestations

- Renal: Hypoperfusion, acute tubular necrosis.

- Pulmonary: Respiratory compromise from mucosal sloughing and secondary infection.

- Gastrointestinal: Diarrhoea, malabsorption, mucosal necrosis (Harris, 2016).

- Sepsis: Common and often fatal, due to loss of skin barrier and immune suppression.

Typical cutaneous findings in the early stages of toxic epidermal necrolysis are illustrated below.

Investigations

Laboratory and histological tests aid in diagnosis and monitoring complications.

- Blood Tests: CBC, renal and liver panels, CRP/ESR, albumin, and autoantibodies.

- Typical Findings: Lymphopenia, anaemia, hypoalbuminaemia (Gerull, 2011).

- Histopathology: Full-thickness epidermal necrosis, subepidermal bullae (Harris, 2016).

- Direct Immunofluorescence: Negative for IgG and C3, ruling out autoimmune blistering disorders (Harris, 2016).

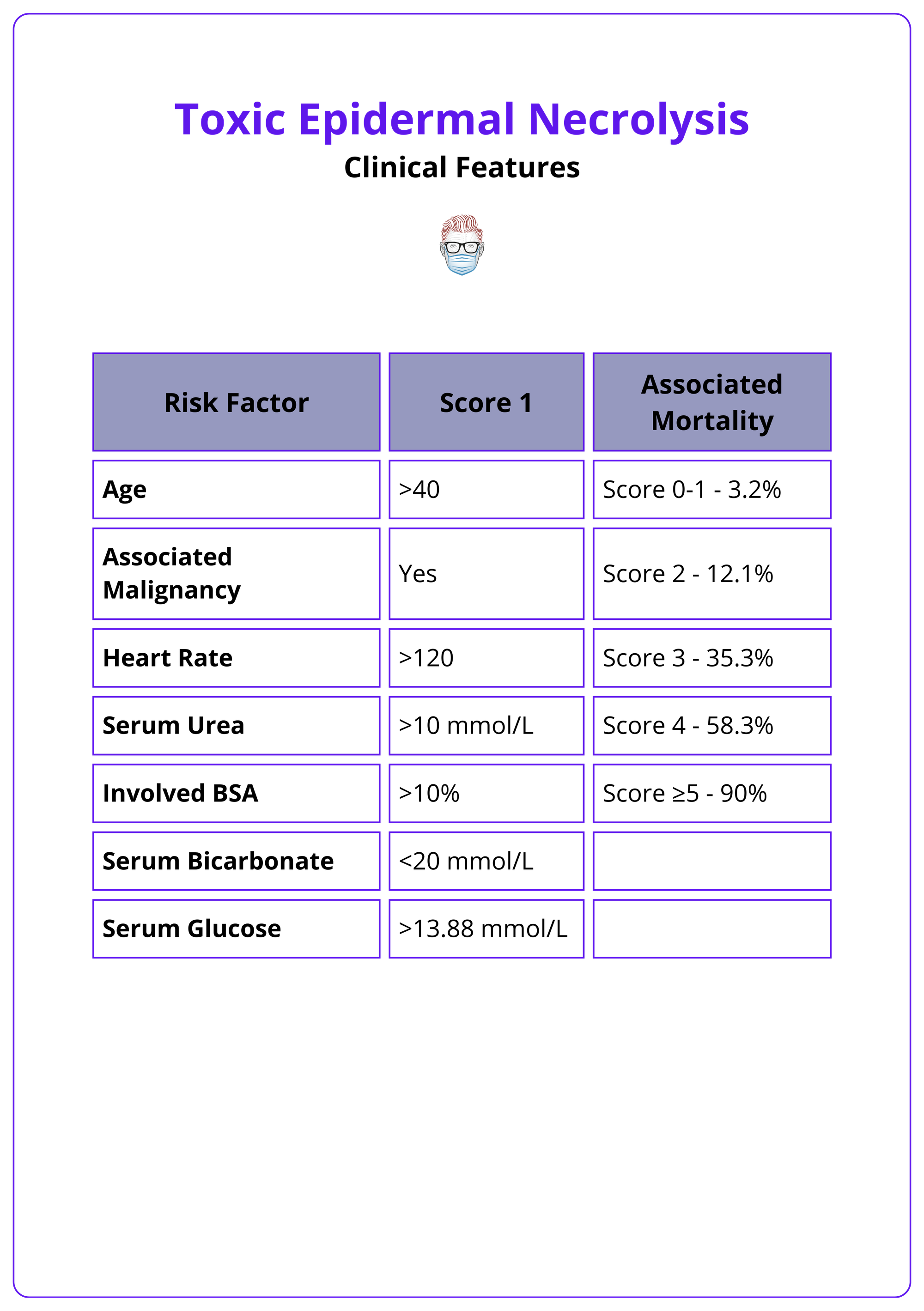

Severity Score for TENS

The SCORTEN (Severity-of-Illness Score for Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis) evaluates seven independent risk factors within the first 24 hours of hospital admission to estimate a patient's mortality risk (Bastuji-Garin, 2000).

The table below summarizes this scoring system.

Differential Diagnosis of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Accurate and timely differentiation from clinically similar conditions is essential, especially in children, to avoid mismanagement and ensure appropriate care.

TEN can mimic several dermatologic disorders that also present with widespread blistering or skin detachment. Distinguishing features such as mucosal involvement, depth of epidermal damage, and histologic findings help clarify the diagnosis.

Conditions with overlapping clinical features must be carefully excluded using history, physical examination, and diagnostic tests.

Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome (SSSS)

- Primarily affects neonates and young children.

- Caused by exfoliative toxins from Staphylococcus aureus.

- Features superficial epidermal cleavage and lacks mucosal involvement (Schwartz, 2013).

- Triggered by infection rather than drugs (Pereira, 2007).

Drug-Induced Linear IgA Dermatosis

- Presents with bullous lesions and annular erythema.

- Direct immunofluorescence shows linear IgA deposition at the dermoepidermal junction (Harris, 2016).

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis (AGEP):

- Sudden eruption of non-follicular sterile pustules.

- Minimal epidermal necrosis and mucosal involvement.

- Resolves quickly upon withdrawal of the causative drug (Schwartz, 2013).

Graft-versus-Host Disease (GVHD):

- Occurs after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

- Skin findings may resemble TEN but usually include lichenoid or sclerodermoid changes.

- Often accompanied by systemic signs of graft rejection.

Erythema Multiforme Major (EM Major):

- Target lesions with limited mucosal involvement.

- Commonly triggered by infections (e.g. herpes simplex virus).

- Considered a distinct condition, not part of the SJS/TEN spectrum (Pereira, 2007).

Erythema multiforme major typically presents with classic “target” lesions, while TEN involves extensive epidermal detachment with blisters forming on flat, purpuric macules—mainly on the trunk and face. Mucosal involvement is also a key distinguishing factor.

Management of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Management is primarily supportive, focusing on wound care and preventing complications.

Therapeutic strategies focus on supportive measures until skin regeneration occurs, alongside emerging adjunct therapies.

- Initial Steps

- Immediate discontinuation of the offending drug.

- Transfer to a burn or intensive care unit (reduces risk of infection, mortality, and length of stay) (Schwartz, 2013).

- Supportive Care

- Aggressive fluid and electrolyte replacement guided by central venous pressure and urine output.

- Nutritional support via enteral feeding.

- Pain management.

- Non-adherent dressings with daily wound care (Gerull, 2011).

- Plasmapheresis to clear offending drug and active metabolites.

- Specific Therapies

- IVIG within 72 hours of bulla onset: Blocks Fas-mediated keratinocyte apoptosis; efficacy remains debated (Schwartz, 2013).

- Cyclosporine: Reduces T-cell activation, with emerging evidence supporting its use (Hoetzenecker, 2016).

- Corticosteroids: Controversial; may benefit early-stage TEN, but some studies have shown steroids to increase mortality (Avakian, 1991).

- Rehabilitation

- Encourage early mobilization.

- Involve physiotherapists and occupational therapists.

Since these patients are usually managed in a Burns unit, plastic surgeons are involved in their care, ranging from wound care to debridement of areas of skin necrosis as indicated.

Conclusion

1. Definition and Severity: TEN is a life-threatening dermatologic condition with >30% skin detachment, extensive mucosal involvement, and high mortality (25–50%).

2. Pathophysiology: TEN results from T-cell-mediated keratinocyte apoptosis, driven by granulysin, perforin, and Fas-Fas ligand interactions.

3. Risk Factors and Triggers: Drugs like sulfonamides, antiepileptics, and NSAIDs are common triggers, with genetic predisposition and HIV increasing risk.

4. Clinical Features and Diagnosis: Painful skin detachment, positive Nikolsky’s sign, and mucosal erosions confirm TEN, with histology showing full-thickness epidermal necrosis.

5. Management: Supportive care (fluid replacement, wound care) is essential, with adjuncts like IVIG or cyclosporine; corticosteroids remain controversial.

6. Differentiation and Prognosis: TEN requires differentiation from SSSS and erythema multiforme; early intervention improves outcomes in specialized care units.

Further Reading

- Harris, Victoria, Christopher Jackson, and Alan Cooper. "Review of toxic epidermal necrolysis." International Journal of Molecular Sciences 17.12 (2016): 2135.

- Schwartz, Robert A., Patrick H. McDonough, and Brian W. Lee. "Toxic epidermal necrolysis: Part I. Introduction, history, classification, clinical features, systemic manifestations, etiology, and immunopathogenesis." Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 69.2 (2013): 173-e1.

- Gerull, Roland, Mathias Nelle, and Thomas Schaible. "Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome: a review." Critical care medicine 39.6 (2011): 1521-1532.

- Avakian R, Flowers FP, Araujo OE, Ramos-Caro FA. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991 Jul;25(1 Pt 1):69-79. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(91)70176-3. PMID: 1880257.

- Pereira FA, Mudgil AV, Rosmarin DM. Toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007 Feb;56(2):181-200. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.04.048. PMID: 17224365.

- Kinoshita Y, Saeki H. A Review of the Pathogenesis of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis. J Nippon Med Sch. 2016;83(6):216-222. doi: 10.1272/jnms.83.216. PMID: 28133001.

- Bastuji-Garin, S., Fouchard, N., Bertocchi, M., Roujeau, J. C., Revuz, J., & Wolkenstein, P. (2000). SCORTEN: a severity-of-illness score for toxic epidermal necrolysis. The Journal of investigative dermatology, 115(2), 149–153.

- Bastuji-Garin S, Rzany B, Stern RS, Shear NH, Naldi L, Roujeau JC. Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol. 1993 Jan;129(1):92-6. PMID: 8420497.

- Schwartz RA, McDonough PH, Lee BW. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: Part II. Prognosis, sequelae, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Aug;69(2):187.e1-16; quiz 203-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.05.002. PMID: 23866879.

- Hoetzenecker W, Mehra T, Saulite I, Glatz M, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Guenova E, Cozzio A, French LE. Toxic epidermal necrolysis. F1000Res. 2016 May 20;5:F1000 Faculty Rev-951. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7574.1. PMID: 27239294; PMCID: PMC4879934.