Summary Card

Overview of Burn Complications

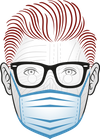

A burn has a multi-organ effect on a patient. A release of inflammatory mediators and neural stimulation results in both local and systemic effects.

Jackson's Burn Wound Model

This describes zones of coagulation (cell death), stasis(damage to microcirculation), and hyperaemia (inflammatory response).

Hypovolaemia

Hypovolemia from a shift in protein and fluid from the intravascular to the interstitial space due to an increase in capillary permeability.

Hypermetabolic Response In Burns

A burn results in changes to metabolism, hormones, cardiorespiratory function, gastrointestinal function, and immunity.

Nutrition in Burn Patients

Nutrition maintains a patient's body mass and reduces the risk of bowel ileus, bacterial translocation, and long-term immunity issues.

Gastrointestinal System in Burns

There are three main concerns: gastric ulceration, ileus, and mucosal damage. It is closely linked to nutrition and enteral feeding.

Kidney Injury in Burns

Renal failure is linked to hypovolemia, medications, cardiac dysfunction, and sepsis. It's exacerbated by haemochromogens.

Electrolyte Imbalance in Burns

Sodium, potassium, and glucose are most commonly affected. Their imbalances change over time as the burn evolves.

Overview Burn Complications

A burn has a multi-organ effect on a patient. A release of inflammatory mediators and neural stimulation results in both local and systemic effects.

The local effects of a burn are based on Jackson's burn model, which describes zones of coagulation, stasis, and hyperaemia.

The systemic effects of a burn include:

- Fluid and electrolytes: hypovolemia, sodium and potassium imbalance.

- Metabolism: hypermetabolism, nutrition.

- Organs: cardiorespiratory, liver dysfunction, renal.

- Infection: sepsis, toxic shock system.

The below flow-chart illustrates the effects of a burn.

Jackson's Burn Wound Model

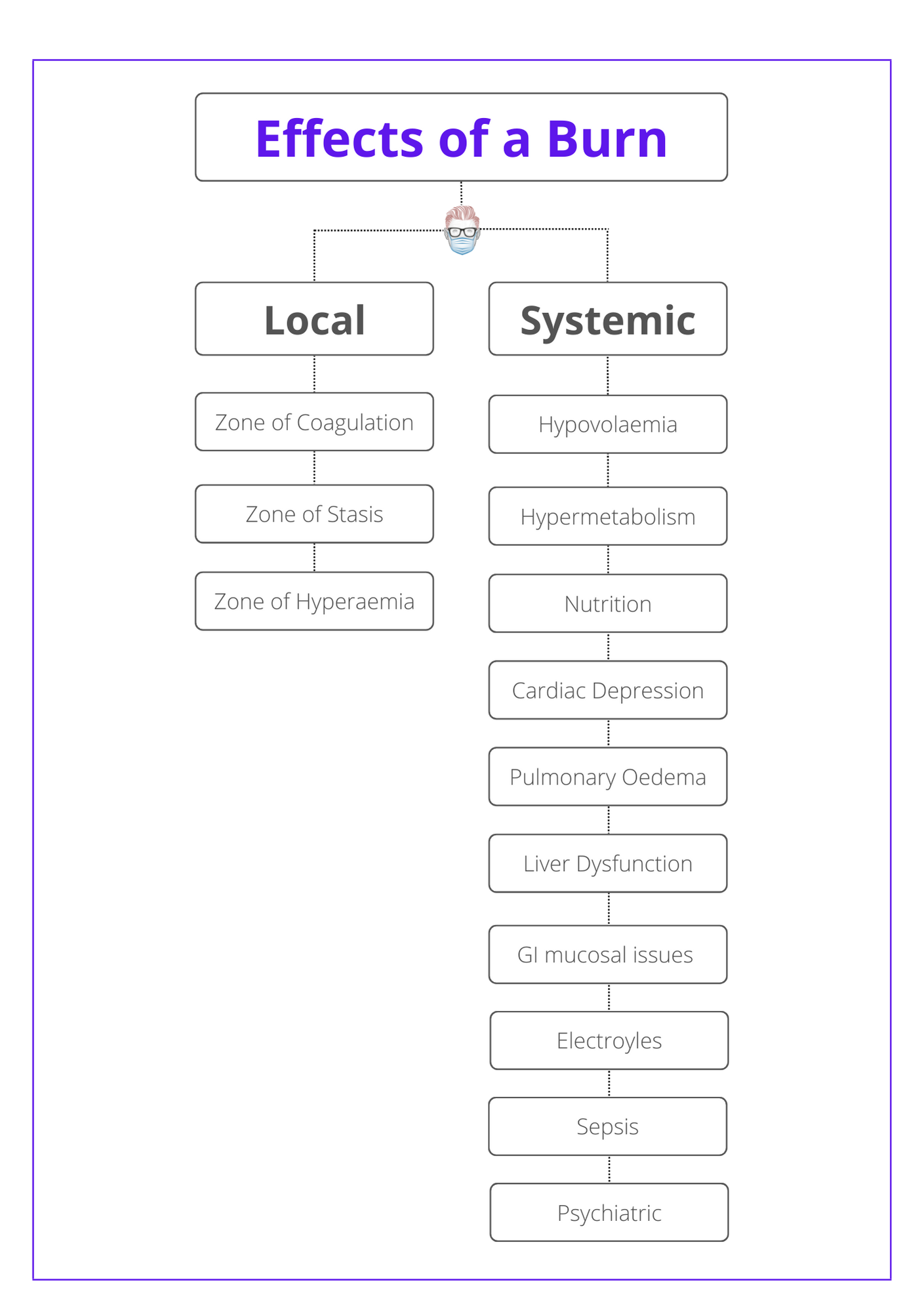

Jackson's burn wound model describes zones of coagulation (cell death), stasis (damage to microcirculation), and hyperaemia (inflammatory response).

Jackson's Burn Wound model states there are 3 zones to a thermal burn injury: coagulation, stasis, and hyperaemia. This is based on the work by Jackson in the 1950s.

The image below shows the 3 zones of a thermal burn injury according to Jackson's burn wound model.

Zone of Coagulation (Cell Death)

- Inner zone (nearest the burn source).

- Heat cannot be conducted away rapidly enough.

- There is immediate coagulation of cellular proteins, there is rapid cell death.

Zone of Stasis (Circulation)

- The intermediate zone surrounding the zone of Coagulative Necrosis.

- Less direct damage to tissue but more damage to the microcirculation.

- If untreated, inflammatory response results in necrosis & burn depth evolve.

- The extent of progress is influenced by the effectiveness of resuscitation.

Zone of Hyperaemia (Inflammation)

- The outermost zone surrounding the region of compromised vasculature.

- Inflammatory mediators result in vasodilation and increased permeability.

- Results in the fluid shift into the interstitial space.

- After this initial response, this zone should return to normal.

- Examples of inflammatory mediators are free oxygen radicals and histamine.

Hypovolemia in Burns

Hypovolemia is the most profound and direct effect of a burn. It is primarily due to a shift in protein and fluid from the intravascular to the interstitial space caused by an increase in capillary permeability.

Hypovolemia results in "burn shock". It begins at a cellular level (Baxter, 1968 & Moyer, 1965 & Arturson, 1979) and is a combination of distributive, cardiogenic, and hypovolemic shock.

Key components of the physiological changes during a burn are:

- Intracellular sodium shift contributes to hypovolemia and cellular oedema.

- Local vasoconstriction and systemic vasodilation form inflammatory and vasoactive mediators.

- A fluid shift from intravascular to interstitial spaces due to Increased vascular permeability from disrupted capillaries.

An accurate assessment of burn depth and total body surface area will allow effective fluid resuscitation of hypovolemia.

Hypermetabolic Response in Burns

Following a hypodynamic period, a hypermetabolic response occurs at a cellular and humoral level resulting in changes to metabolism, hormones, cardiorespiratory function, gastrointestinal function, and immunity.

The response to a burn can be described as an "ebb and flow". The ebb is a hypodynamic period that occurs ~48 hours after a burn, which is then followed by a hypermetabolic flow phase. This response does not return to "normal" until wound remodeling is complete.

Clinically, these patients have tachycardia, hyperthermia & protein wasting.

Physiology

At a physiological level, the hypermetabolic response occurs due to:

- Hyperdynamic circulation: increased cardiac output, increased oxygen consumption and C02 production.

- Hyperthermia: core temperature can be chronically elevated.

- Hormone shift: increased stress hormones cortisol, catecholamine and reduced anabolic hormones (growth hormone, insulin, and anabolic steroids).

- Glucose increase: Increased glycogenolysis causes hyperglycemia (excess glucose is metabolised anaerobically resulting in lactate production) to create a diabetic-like state.

- Lactate increase: Anaerobic metabolism resulting in carbohydrate cycling (less energy than aerobic metabolism) with reduced nitrogen balance.

Effect of Response

This results in a series of complications and morbidities:

- Reduced immunity at a cellular and humoral level results in increased infections and decreased healing. Circulating levels of immunoglobulins are reduced.

- Loss of body mass from the breakdown of muscle protein impairs wound healing and rehabilitation. There is an increased central deposition of fat, decreased bone mineralization, and decreased longitudinal growth of the body.

- GI disturbances: increase in bacterial translocation that can be minimized by beginning very early enteral nutrition.

Nutrition in Burn Patients

The role of nutrition is to maintain the patient's body mass and reduce the risk of bowel ileus, bacterial translocation, and long-term immunity issues.

Nutrition is a key aspect of burn management due to the hypermetabolic response affecting lean body mass, and large shifts in fluids and electrolytes.

Aims

Normal gastric feeding as soon as possible after burn injury.

- Maintain a patient's body weight.

- Maintain protein.

- Stabilise fluids and electrolyte disturbances.

During this time, patients should be weighed daily, bowel movements recorded, and documentation of extra eating habits or requests.

Nutritional Formulas

The nutritional requirements in burn patients are related to the Resting Energy Expenditure (REE). This can be calculated in different ways by:

- Calorimetric testing of oxygen consumption and C02 production.

- Schofield equation (for basal metabolic rate).

- Harris-Benedict Equation (for resting energy expenditure).

The number of calories required in a burn patient can be calculated by:

- Adults: Curreri Formula: 25kcl/kg + 40kcal/%TBSA every 24 hours.

- Children: Galveston Formula: 1500kcal/m2 + 1500kcal/m2 BSA burn.

The Galveston formula requires the calculation of BSA via the Du Boi Formula: BSA [m2] = Weight [kg]0.425 × height (cm)0.725 × 0.007184.

Route of Nutrition

Burns patients can receive their nutrition through 3 routes: oral, enteral, or parenteral.

Here are the key points regarding different options.

- Oral: recommended if clinically feasible.

- Enteral via nasogastric or nasojejunal feeding to help maintain mucosa, reduce bacterial translocation (gram-negative), and prevent intestinal ileus.

- Parenteral: not routinely used due to effects on fatty liver infiltration, reduced immune function, and sepsis. It is associated with impaired mucosal immunity and enhanced endotoxin translocation.

Paediatric Patients

- Children are more prone to gastric dilatation. This can be overcome through a nasogastric tube on free drainage.

- A high metabolic rate results in less tolerance to nutritional deprivation.

- Very early enteral feeding should be established as soon as they arrive at the definitive treatment centre.

Gastrointestinal System in Burns

The gastrointestinal system and genitourinary system are commonly affected by a burn. The both relate to a lack of flow (water or food) in patients.

Gastrointestinal complications are closely linked to nutrition in the previous section. There are three main concerns: gastric ulceration, ileus, and mucosal damage.

- Ileus: an adynamic bowel can occur & is prevented by early enteral nutrition.

- Mucosa: mucosa damage occurs due to inadequate nutrition. This results in bacterial translocation (bowel circulation) & subsequent gram-negative sepsis.

- Ulceration: high risk of acute gastric ulceration that can be reduced by proton-pump inhibitors, H2 antagonists, and enteral feeding.

Kidney Injury in Burns

Renal failure in burns has a multifactorial aetiology often linked to hypovolemia, medications, cardiac dysfunction, and sepsis. It is exacerbated by haemochromogens in the urine.

Acute Kidney Injury

Renal failure in burns has a multifactorial aetiology that is often related to hypovolemia, medications, cardiac dysfunction, and sepsis. It can be treated by:

- Fluid resuscitation

- Monitoring urine output: normal is 0.5–1.0 ml/ kg/hr in adults, 1.0–1.5 ml/kg/hr in children. This should be increased in AKIs or myoglobinuria.

- Mannitol: renoprotective osmotic diuretic.

Hemoglobinuria

Myoglobin and haemoglobin are haemochromogens that colour the urine a dirty red. They are released by tissue injury, especially muscle, and deposition in the proximal tubules of the kidney. This can lead to acute renal failure.

This is treated in a similar method to acute kidney injury as discussed above.

- Increase urine output to 2mL/kg/hr.

- Consider mannitol.

- Consider performing a fasciotomy (as opposed to an escharotomy which doesn’t release deep muscle fascia).

Oliguria

Oliguria is low urine output. It is closely linked to inadequate fluid resuscitation. Its management is to increase the rate of infusion, monitor urine output, and titrate accordingly. Diuretics are not routinely recommended for isolating oliguria.

Patients at high risk of requiring more fluids are (Maybauer et al, 2009):

- Children

- Delayed resuscitation

- Inhalation or electrical injury

Electrolyte Imbalance in Burns

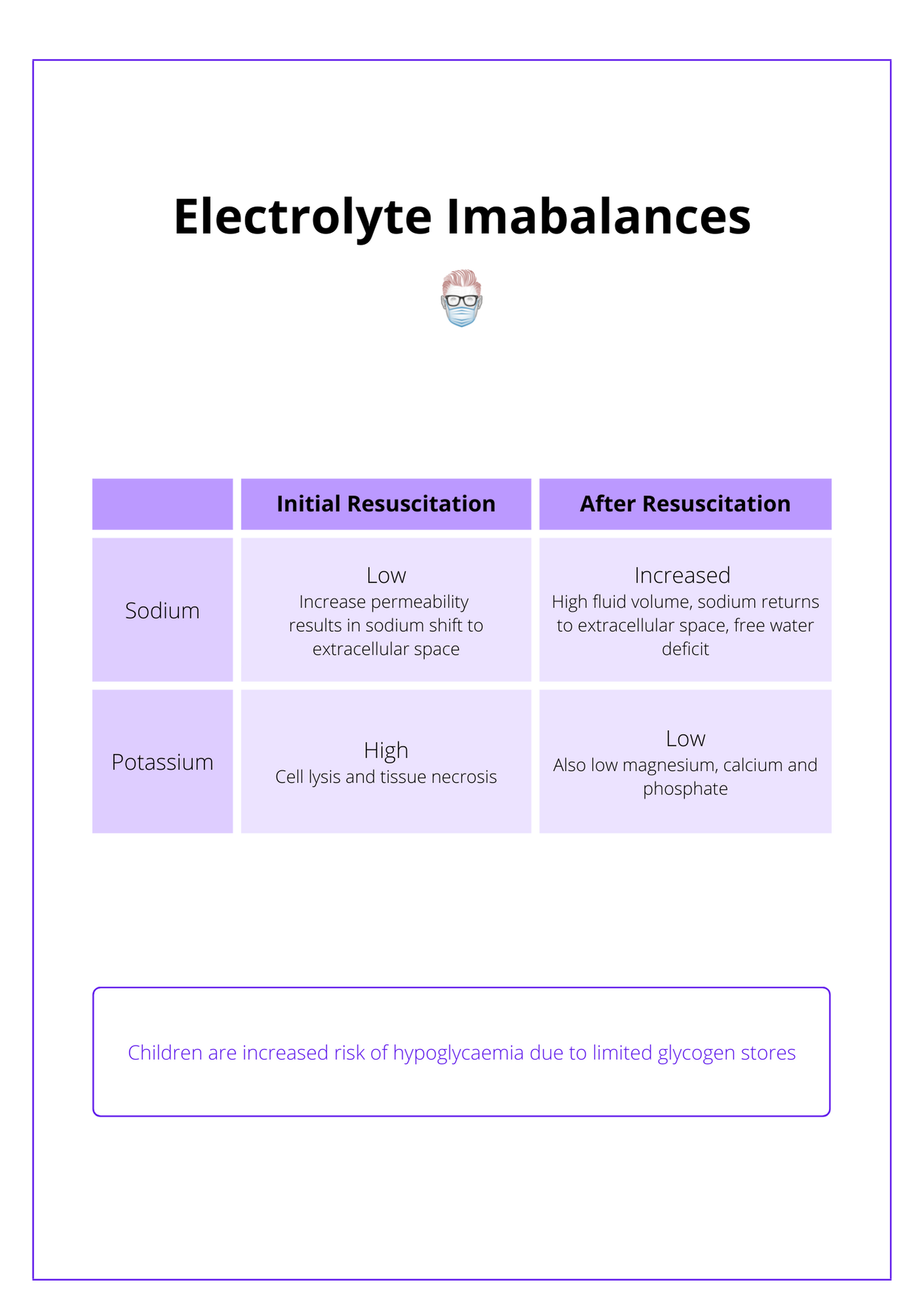

Sodium, potassium and glucose are the commonly affected electrolytes in burn patients. Their imbalances change over time as the burn evolves.

A burn patient is the victim of major fluid and electrolyte shifts.

The two common electrolyte disturbances are sodium and potassium. Other affected electrolytes include calcium, magnesium, and phosphate. This is illustrated in the diagram below.

Sodium

- Initially low as sodium exits the extracellular space due to increased vessel permeability. Paediatrics are at increased risk of dilutional hyponatremia.

- After resuscitation, it can be high due to fluids (contains sodium) and sodium returning to the extracellular space. This is compounded by an acute kidney injury, resolution of oedema (concentrates the sodium), and a free water deficit.

Potassium

- Initially high due to potassium leaks from cell lysis and tissue necrosis.

- Common in electrical burns.

- Bicarbonate and glucose plus insulin may be required to correct this problem.

Glucose

- Children are prone to hypoglycemia due to limited glycogen stores.

- Blood glucose and electrolyte levels should be measured regularly.

- Early enteral feeding or addition of dextrose to the electrolyte solution.

Conclusion

1. Pathophysiology of Burns: You've learned how burns result in multi-organ effects, involving the release of inflammatory mediators and neural stimulation.

2. Burn Complications: You now understand the complex complications associated with burns, including hypovolemic shock, hypermetabolic response, and specific organ system impacts.

3. Burn Severity and Zones: You've gained knowledge on Jackson's Burn Wound Model which describes the three zones of damage in a burn area.

4. Nutritional Needs in Burn Patients: You are familiar with the crucial role of nutrition in managing burn patients, addressing the hypermetabolic state, and preventing complications.

5. Electrolyte Management: You've explored the management of common electrolyte imbalances in burn patients, understanding how shifts in sodium, potassium, and glucose can impact patient recovery.