Summary Card

Indications for Resuscitation

Fluid resuscitation is indicated in burns with < 15% TBSA in adults and >10% TBSA in children.

Pathophysiology of "Burn Shock"

Fluid shifts from intravascular to interstitial spaces, intracellular sodium shifts, local vasoconstriction, and systemic vasodilation.

Types of Fluids

Crystalloids and colloids are the mainstays of fluids in burns resuscitation. Most formulas are based on Hartmans/Ringers Lactate.

Formulas

The Parkland Formula (4mL x %TBSA x kg) is the most widely used formula for the first 24 hours of fluid resuscitation.

Resuscitation in Children and the Elderly

Maintenance with 5% dextrose & resuscitation fluid to overcome proportionally greater surface area & reduced hepatic glycogen stores.

Complications

This can be due to under- or over-resuscitation. Too much fluid can result in oedema and cardiac and respiratory compromise.

Indications for Fluid Resuscitation

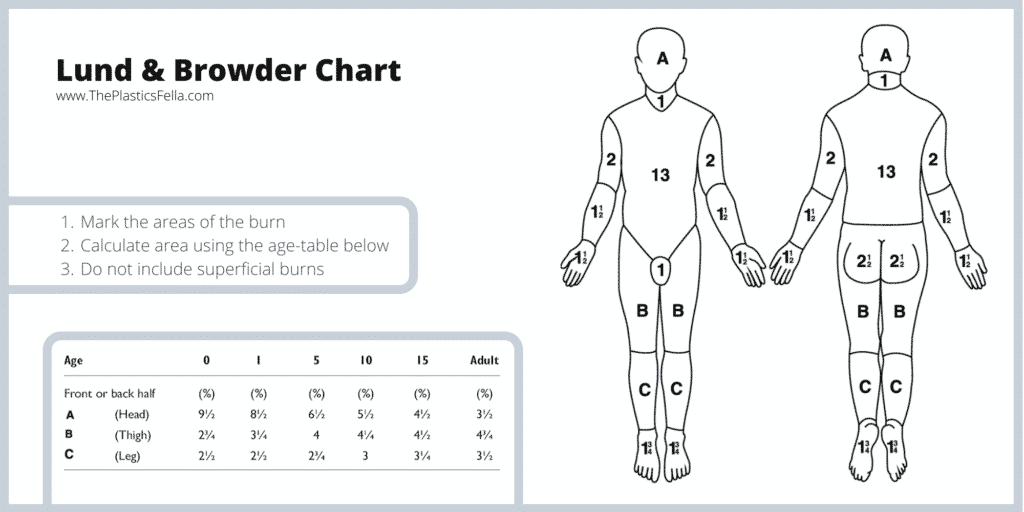

Fluid resuscitation is indicated for adults with burns over 15% total body surface area (TBSA) and children over 10% TBSA.

The American Burns Association state that "burns greater than 20% TBSA should undergo formal fluid resuscitation using estimates based on body size and surface area burned" (Pham et al., 2008).

Globally speaking, the following two are recommended guidelines for fluid resuscitation in a burn based on burn size.

- Adults > 15% TBSA

- Children >10% TBSA

The image below illustrates the Lund & Browder Chart for classifying burns.

The goal of fluid resuscitation is to prevent rather than treat burn shock. This goal is achieved in the following ways:

- Restore circulating volume.

- Preserve tissue perfusion.

- Avoid ischemic extension of the burn wound.

Pathophysiology of Burn Shock

Burn shock occurs at the cellular level due to intracellular sodium shifts causing hypovolemia and cellular edema, local vasoconstriction paired with systemic vasodilation, and fluid shifts from intravascular to interstitial spaces.

Burn shock begins at a cellular level (Baxter, 1968 & Moyer, 1965 & Arturson, 1979). It is a combination of distributive, cardiogenic, and hypovolemic shock.

Key components of the physiological changes during a burn are:

- Intracellular sodium shift contributes to hypovolemia and cellular oedema.

- Local vasoconstriction and systemic vasodilation form inflammatory and vasoactive mediators.

- A fluid shift from intravascular to interstitial spaces due to increased vascular permeability from disrupted capillaries.

This pathophysiological response is compounded by a reduced cardiac output and increased systemic vascular resistance. It is also influenced by burn depth and total body surface area.

There are two main "fluid compartments".

- Intracellular: fluid inside the cell (the majority of fluid in the body).

- Extracellular: fluid outside the cell that consists of intravascular and interstitial fluid.

Types of Fluids

Commonly used fluid formulas include Parkland and modified Brooke formulas. Most fluid regimes are crystalloids, colloids are used less regularly.

There is no absolute consensus on fluid formula or fluid type.

It is important to replace the fluid in the intravascular compartment to avoid end-organ hypoperfusion and ischemia. Isotonic crystalloids, hypertonic solutions, and colloids can all be used to effectively restore plasma volume, but every solution has advantages and disadvantages.

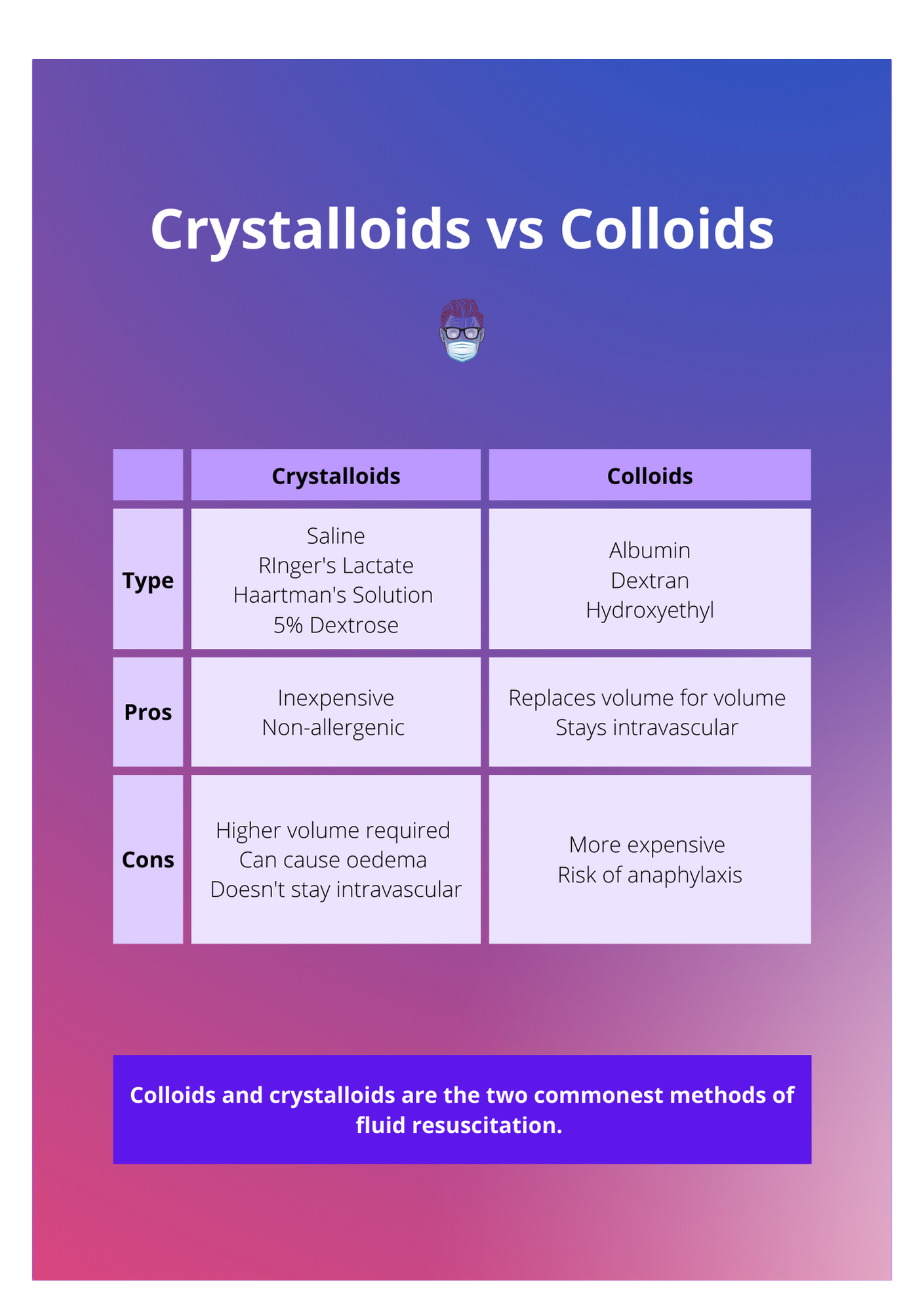

The table below breaks down the pros and cons of crystalloids and colloids.

Crystalloids

A crystalloid fluid is an aqueous solution of mineral salts and other small, water-soluble molecules.

Most commercially available crystalloid solutions are isotonic to human plasma. Administration of large volumes of crystalloid during burn resuscitation decreases plasma protein concentration.

Commonly used crystalloids include:

- Saline: Normal Saline, Hypertonic Saline

- Ringer's Lactate (also called Haartman's solution)

- 5% Dextrose (used in paediatric burns)

Colloids

Several recent studies have suggested that colloid is useful in decreasing total fluid administration, thereby reducing the risk of “fluid creep”, and oedema formation.

There is little consensus with respect to indications or dosing (Eljaiek R et al, 2017). Colloid options available include:

- Albumin

- Dextran

- Hydroxyethyl

Albumin Replacement

Albumin should be replaced in a major burn. The Muir and Barclay formula calculates the volume of human albumin solution required in the first 36 hours:

- 0.5mL X kg X TBSA% to be infused in each time period.

- Time periods are 3 x 4 hours, 2 x 6 hours, 1 x 12 hours.

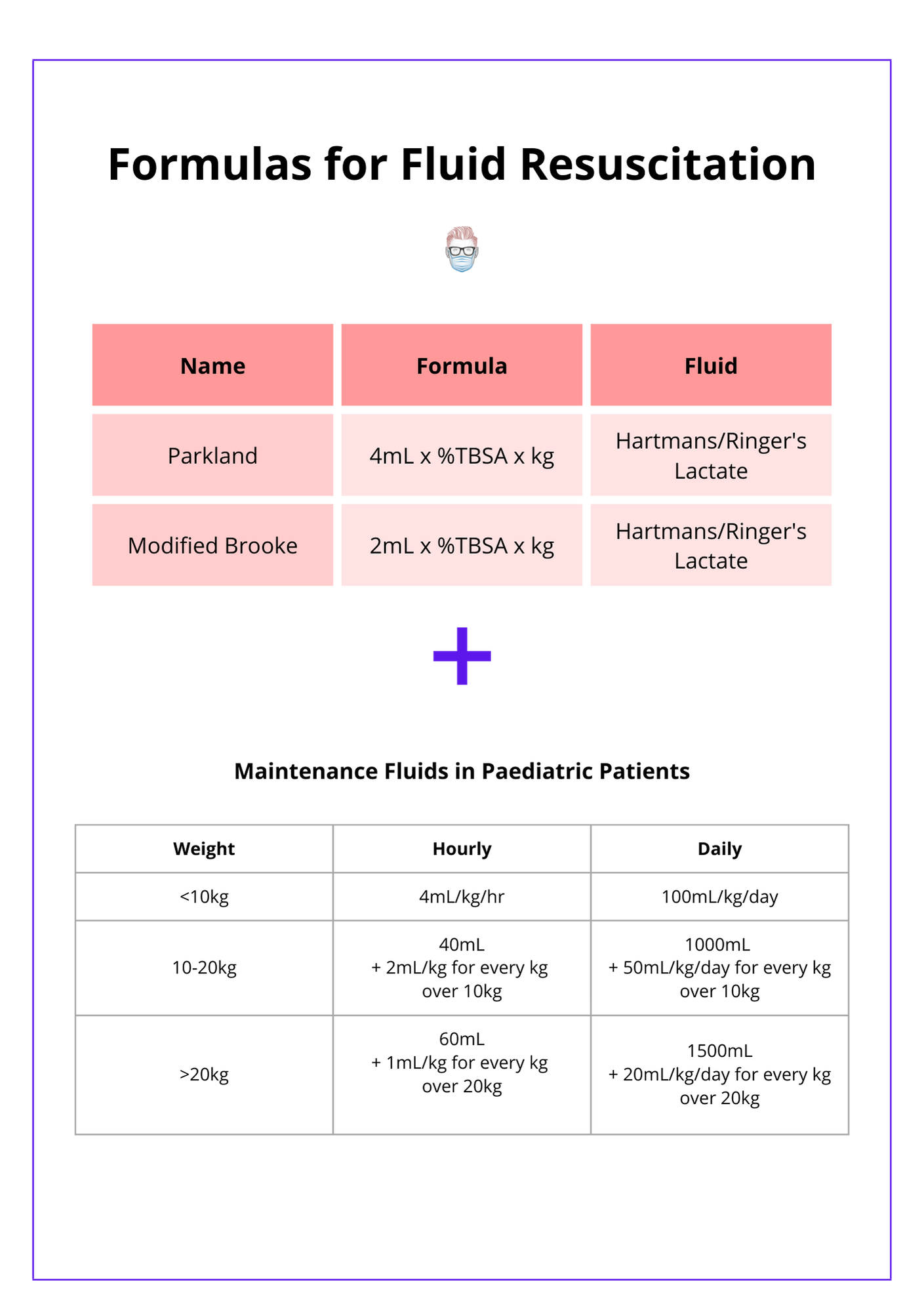

Formulas for Burn Resuscitation

Burn resuscitation utilizes formulas to calculate fluid needs. They require ongoing adjustment based on physiological responses such as urine output, vital signs, and blood gas metrics to ensure effective treatment.

There are different formulas used to calculate fluid requirements in burn resuscitation. These include the commonly used Parkland formula and modified Brooke formula.

These formulas are classified in the table below.

Parkland Formula

4ml x %TBSA x kg

The Parkland formula (also known as the Baxter Formula) was developed in 1968 by Baxter and Shires. It remains one of the most widely used resuscitation crystalloid-only formulas. It is calculated as 4ml x %TBSA x kg. The first half is given in the first 8 hours, the second half is given in the next 16 hours.

First 24 hours after burn:

- 4ml x %TBSA x kg in the first 24 hours.

- 1st half is in the first 8 hours, and 2nd half is in the next 16 hours.

- Increase fluids in deeper burns, delayed results, & inhalation (Baxter, 1974 & 1978).

Second 24 hours after burn:

- There is less attention to colloid recommendations for the second 24 hours.

- Colloids are given as 20–60% of calculated plasma volume. No crystalloids.

- Glucose in water to maintain a urinary output of 0.5–1 ml/hr in adults & 1 ml/hr in children.

Variations:

- The rate of fluid infusion should be adjusted to the physiological response.

- The volume of fluid should be titrated to maintain a urine output of approximately 0.5–1.0 ml/ kg/hr in adults and 1.0–1.5 ml/kg/hr in children.

- Other variables, including the heart rate, blood pressure, lactate, base deficit, and mental status, must be considered simultaneously.

Modified-Brooke Formula

2ml x %TBSA x kg:

The original Brooke formula proposed by Dr Artz at the Army Burn Center was composed of both crystalloid and colloid fluids.

Initial 24 hours:

- 2ml x %TBSA x kg in adults and 3ml x %TBSA x kg in children.

- No colloids.

- Ringer Lactate or Hartman's solution.

Next 24 hours:

- Colloids at 0.3–0.5 ml/kg/% burn and no crystalloids are given.

- Glucose in water is added to maintain good urinary output.

Assessing Response to Fluids

The rate and volume of fluid resuscitation should be titrated and adapted to specific physiological responses.

Key parameters include:

- Urine Output: >0.5mL/kg/hr in adults, >1mL/kg/hr in children.

- Vital Signs: pulse, blood pressure, respirator rate.

- Temperature Core-peripheral temperature gradient.

- Urine osmolality.

- Arterial Blood Gas: Lactate and base excess.

Resuscitation in Children and the Elderly

There are special considerations for fluid resuscitation in children and the elderly due to reduced physiological reserves and medical comorbidities.

Paediatrics

Maintenance fluid with 5% dextrose in addition to resuscitation fluid is required in the paediatric population. This is because:

- Reduced physiological reserves.

- Proportionally greater surface area than adults.

Glucose homeostasis is an important parameter in children.

- Hepatic glycogen stores in young children are depleted after ~12 hours

- Important to provide sufficient glucose substrates during the first 24 hours of re-suscitation.

- Achieved by adding dextrose to the maintenance fluid or early enteral nutrition.

Elderly

The elderly population are compounded by medical comorbidities and a decreased baseline cardiac and pulmonary function. This results in an increased risk of volume overload complications. Hemodynamic monitoring should be used in concert with UOP to optimize perfusion and cardiac function.

Complications of Fluid Resuscitation

Precise fluid titration in burn resuscitation is essential to avoid high morbidity from under-resuscitation, leading to burn shock, organ failure, inadequate perfusion, and over-resuscitation.

Precise titration of fluid rate is critical due to the high morbidity of both under-resuscitation and over-resuscitation.

Complications of Under-Resuscitation

- Uncontrolled burn shock.

- Inadequate organ perfusion.

- Organ failure.

Complications of Over-Resuscitation

- Increases the risk of massive oedema formation.

- Elevated compartment pressures including the abdominal, ocular, and extremity compartments.

- Conversion of superficial to deep burn depth.

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Conclusion

1. Fluid Resuscitation: You've understoood the indications for fluid resuscitation in burn patients, recognizing the critical thresholds of total body surface area (TBSA) affected in adults and children.

2. Pathophysiology and Fluid Types: You've explored the pathophysiology of burn shock and learned about the types of fluids used in resuscitation and their specific applications based on the burn severity.

3. Resuscitation Formulas: You understand the application formulas like the Parkland and Modified-Brooke formulas for calculating initial fluid needs and adjusting treatment.

4. Addressing Special Populations: You are familiar with the unique considerations required for fluid resuscitation in children and the elderly, acknowledging their distinct physiological and medical needs.

5. Complications and Management Strategies: You've reviewed the potential complications associated with under- and over-resuscitation, learning how to balance fluid therapy to prevent complications.

Further Reading

- Pham TN, Cancio LC, Gibran NS; American Burn Association. American Burn Association practice guidelines burn shock resuscitation. J Burn Care Res. 2008 Jan-Feb;29(1):257-66. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31815f3876. PMID: 18182930.

- Baxter CR, Shires T. Physiological response to crystalloid resuscitation of severe burns. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1968 Aug 14;150(3):874-94. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1968.tb14738.x. PMID: 4973463.

- MOYER CA, MARGRAF HW, MONAFO WW Jr. BURN SHOCK AND EXTRAVASCULAR SODIUM DEFICIENCY--TREATMENT WITH RINGER'S SOLUTION WITH LACTATE. Arch Surg. 1965 Jun;90:799-811. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1965.01320120001001. PMID: 14333526.

- Arturson G, Jonsson CE. Transcapillary transport after thermal injury. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1979;13(1):29-38. doi: 10.3109/02844317909013016. PMID: 451475.

- Monafo WW. The treatment of burn shock by the intravenous and oral administration of hypertonic lactated saline solution. J Trauma. 1970 Jul;10(7):575-86. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197007000-00006. PMID: 5447485.

- Shimazaki S, Yukioka T, Matuda H. Fluid distribution and pulmonary dysfunction following burn shock. J Trauma. 1991 May;31(5):623-6; discussion 626-8. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199105000-00005. PMID: 2030508.

- Eljaiek R, Heylbroeck C, Dubois MJ. Albumin administration for fluid resuscitation in burn patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Burns. 2017 Feb;43(1):17-24. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2016.08.001. Epub 2016 Sep 6. PMID: 27613476.

- Baxter CR. Fluid volume and electrolyte changes of the early postburn period. Clin Plast Surg. 1974 Oct;1(4):693-703. PMID: 4609676.

- Baxter CR. Problems and complications of burn shock resuscitation. Surg Clin North Am. 1978 Dec;58(6):1313-22. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)41693-2. PMID: 734611.

- Pruitt BA Jr, Mason AD Jr, Moncrief JA. Hemodynamic changes in the early postburn patient: the influence of fluid administration and of a vasodilator (hydralazine). J Trauma. 1971 Jan;11(1):36-46. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197101000-00003. PMID: 5099912.

- Pruitt BA Jr. Protection from excessive resuscitation: "pushing the pendulum back". J Trauma. 2000 Sep;49(3):567-8. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200009000-00030. PMID: 11003341.