In this week's edition

- ✍️ Letter from P'Fella

Two types of trainees and the gap between education & training. - 🤓 The Sunday Quiz

How well do you know facial nerve palsy? - 🖼️ Image of the Week

Superficial nerves of the head & neck. - 🚑 Technique Tip

Masseteric-innervated free gracilis for facial reanimation. - 📖 What Does the Evidence Say?

Is faster always better in facial reanimation? - 🔥 Articles of the Week

Bell’s palsy, muscle transfer for facial reanimation, & House-Brackmann system for grading facial nerve function. - 💕 Feedback

Suggest ideas & give feedback!

A Letter from P'Fella

Two Types of Trainees and The Gap Between Education & Training

But real training doesn’t happen in lecture halls. It happens between bleeps, before ward rounds, and minutes before decisions.

We built education for readers, while trainees live in a world of retrieval.

Two Ways Trainees Show Up

When you strip everything back, every trainee arrives in one of two modes: Task-first or topic-first.

That single difference dictates everything about how they behave.

Task-first learners arrive with one question and zero patience. They’re not “learning” in the traditional sense. Instead they’re trying to survive a clinical decision.

The data is blunt:

- They arrive via Google

- They read one article for ~53 seconds

- Only 16% ever open a second page

This isn’t laziness. It’s reality. It’s the digital equivalent of grabbing a senior in the corridor: urgent question → fast answer → back to the patient.

Here’s the uncomfortable part: this is 80% of trainees. Task-first learning isn’t a niche. It’s the default operating mode of modern surgery.

Then there’s the other group.

Topic-first learners come intentionally. They arrive directly. And their behaviour flips. They stay longer. They read more. They explore. The content hasn’t changed — their intent has.

This is where education platforms like The Plastics Fella must stop acting like a search engine and start acting like a mentor.

The Mistake We Nearly Made

When I first saw that 80% figure, the conclusion felt obvious.

“The world has become retrievers. Reading is dead.”

But assumptions are dangerous, especially in education. So instead of reacting, we tested it. Properly.

What we found wasn’t that deep learning had disappeared. It was that timing matters. Trainees don’t want long-form education instead of retrieval. They want it after.

First, help me right now.

Then teach me properly.

Most education systems only serve the second moment and completely ignore the first.

The Real Lesson

If surgical education wants to stay relevant, it has to stop pretending trainees live in lecture halls and start designing for the moments that actually define training.

The quiet evening of reading still matters. But so does the chaotic minute before a decision.

Build for both, or you build for no one.

With love,

P’Fella ❤️

The Sunday Quiz

How Well Do You Know Facial Nerve Palsy?

Join this round of our Weekly Quiz in each edition of thePlasticsPaper. This is the third round of seven rounds!

The top scorer wins our Foundations textbook at a discount!

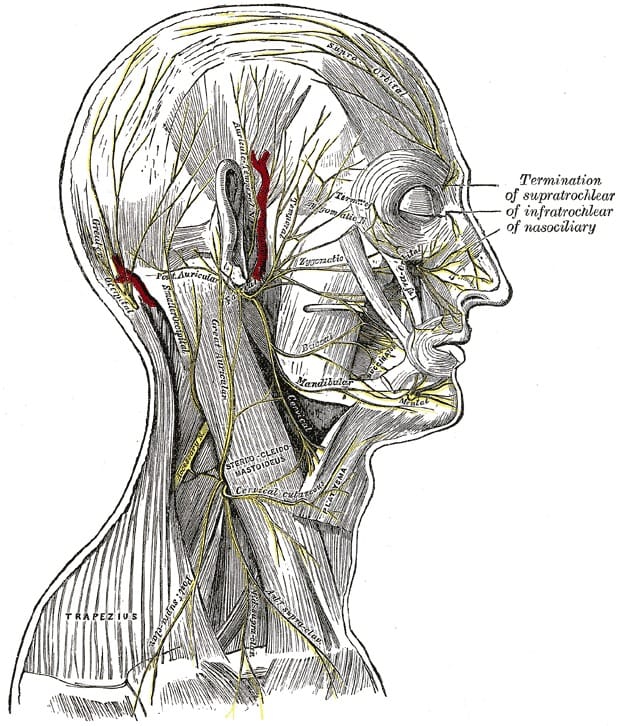

Image of the Week

Superficial Nerves of the Head & Neck

This week's image shows the superficial nerve anatomy of the face, scalp, and lateral neck, highlighting the facial nerve branches in relation to key cutaneous sensory nerves.

While facial nerve palsy is a motor deficit, understanding this layered anatomy is essential:

- to avoid iatrogenic nerve injury during facial surgery,

- to differentiate motor weakness from sensory disturbance, and

- to safely plan incisions, dissections, and nerve blocks.

Key landmarks include the extratemporal facial nerve branches as they traverse the face, alongside sensory nerves such as the supratrochlear, infratrochlear, nasociliary, and auriculotemporal nerves. The close relationship between motor nerves, sensory nerves, and vascular structures explains why facial procedures carry both functional and sensory risk.

Technique Tip

Masseteric-Innervated Free Gracilis for Facial Reanimation

In long-standing facial nerve palsy with irreversible muscle denervation, a free gracilis muscle flap innervated by the masseteric nerve provides reliable, powerful dynamic smile restoration.

The masseteric nerve offers:

- High axonal load

- Short reinnervation distance

- Predictable and early muscle activation

Early post-operative movement is volitional (smile triggered by jaw clenching).

Masseteric innervation prioritises strength and reliability, making it ideal in:

- Long-standing palsy

- Failed nerve grafts

- Older patients or those unsuitable for cross-facial nerve grafting

This video demonstrates free gracilis transfer with masseteric nerve coaptation.

What Does the Evidence Say?

Is Faster Always Better in Facial Reanimation?

Masseteric nerve transfer provides rapid and reliable reinnervation, typically within 3-6 months, with greater oral commissure excursion due to the strength of the masseteric nerve input. However, smiles are predominantly volitional, with low rates of true spontaneity, as cortical activation is linked to mastication rather than emotional expression.

CFNG reinnervates more slowly, often taking up to 18-24 months, but achieves significantly higher rates of spontaneous, emotion-driven smiling by recruiting neural input from the contralateral facial nerve. Commissure excursion is generally lower than with masseteric transfer, but smile quality is more natural, particularly in younger patients and when nerve graft lengths are short.

Dual innervation strategies combining CFNG and masseteric nerve transfer aim to balance early power with long-term spontaneity. Comparative studies demonstrate similar overall facial outcome scores, including eFACE assessments, compared with single-nerve approaches, with gradual improvement in resting tone and facial symmetry over time, at the cost of increased surgical complexity.

Overall, no single technique is superior. Reinnervation strategy should be individualised based on patient age, duration of paralysis, comorbidities, and whether speed or spontaneity is the primary goal, with shared decision-making central to management.

Sources:

(Fattah, 2012)

(Hontanilla, 2015)

(Terzis, 2009)

(Terzis, 2008)

(Biglioli, 2018)

(Banks, 2015)

Articles of the Week

3 Interesting Articles with One-Sentence Summaries

Early oral corticosteroids started within 72 hours of symptom onset significantly improve recovery in Bell’s palsy, achieving higher complete facial nerve recovery rates and faster functional return, establishing steroids as the standard of care for acute facial paralysis.

Single-stage gracilis free muscle transfer achieves comparable flap survival and long-term functional and aesthetic outcomes to two-stage facial reanimation, while reducing operative time, hospital stay, and overall morbidity, supporting its use as an efficient and cost-effective approach for long-standing facial paralysis.

The House-Brackmann scale provides a simple, validated 6-grade classification of facial nerve dysfunction from Grade I (normal) to Grade VI (total paralysis), enabling consistent clinical assessment, outcome reporting, and communication across providers managing facial paralysis.