Summary Card

Overview

Facelift, or rhytidectomy, addresses facial aging by lifting and repositioning the SMAS and soft tissues to improve midface, jawline, and neck definition.

Relevant Anatomy

The SMAS is the key layer in facelift surgery, surrounding the mimetic muscles, while the facial nerve (CN VII) and retaining ligaments are critical landmarks, with the nerve requiring careful preservation.

Clinical Assessment & Indications

A thorough assessment considers medical history, medications, prior treatments, and facial anatomy. Goals include restoring contours, volume, and tightening for a natural, refreshed appearance.

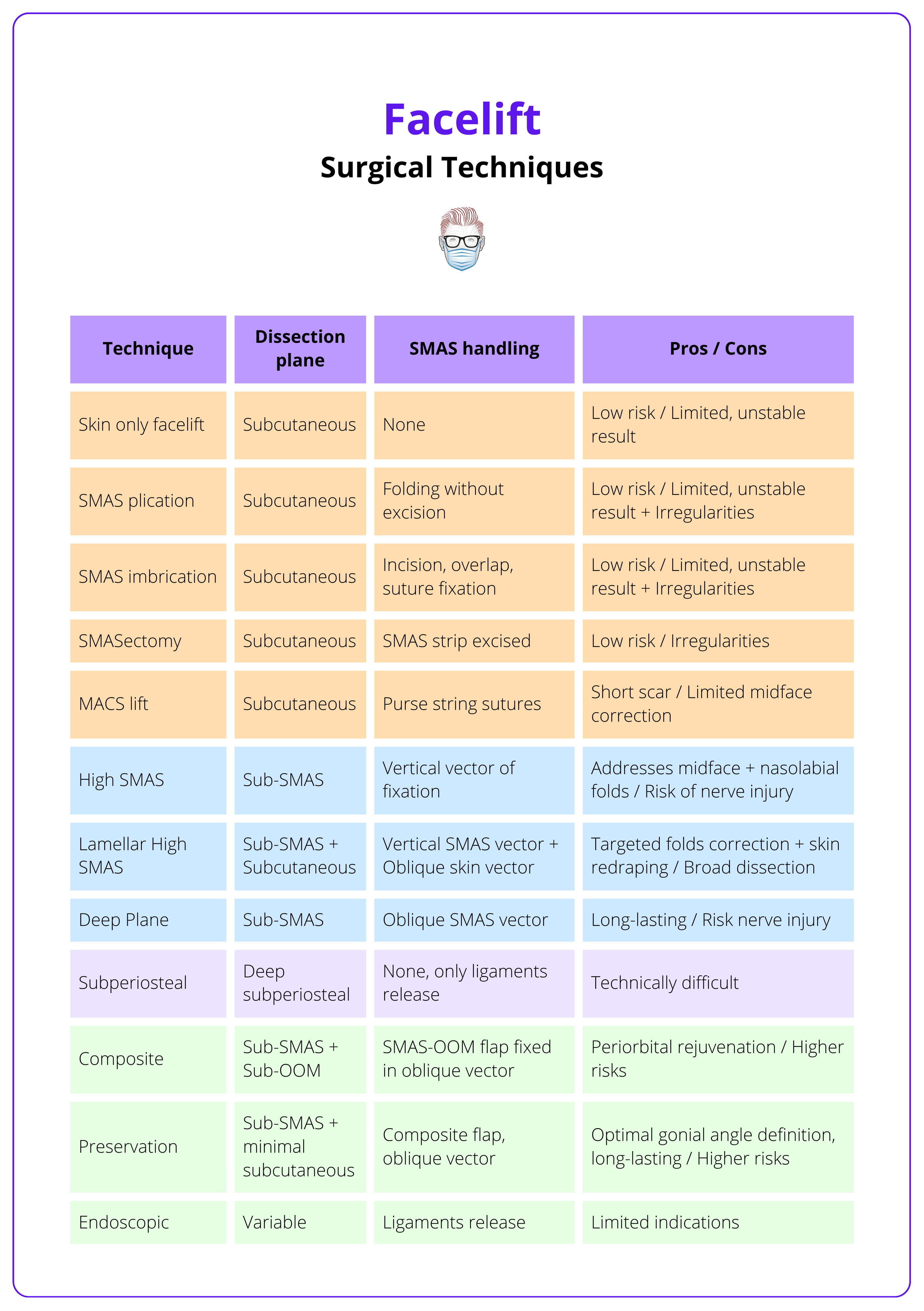

Surgical Techniques

Multiple facelift techniques exist, differing in dissection depth, SMAS handling, and lift vector. Ranging from skin-only to deep plane and preservation methods, with distinct indications, risks, and outcomes.

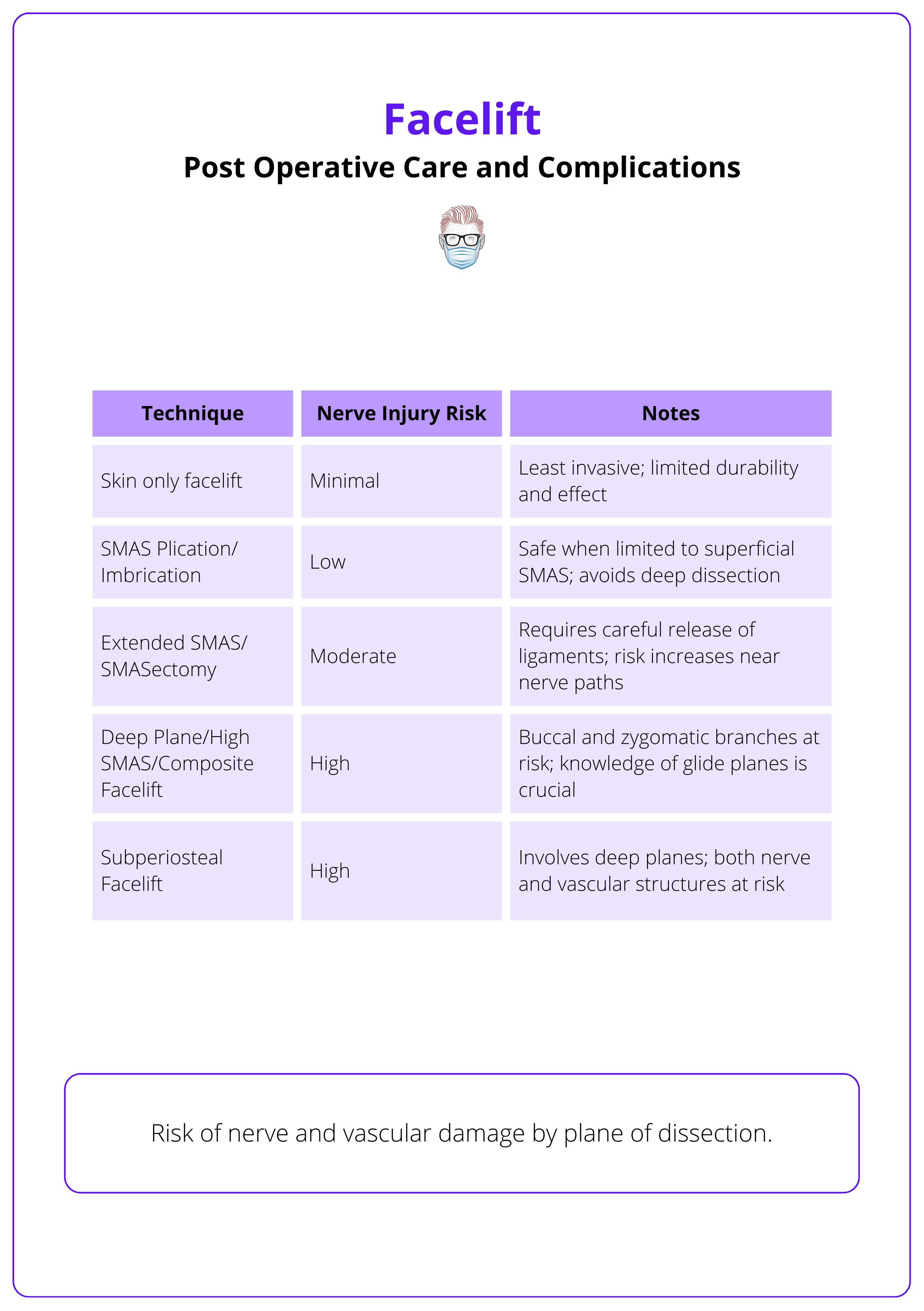

Postoperative Care & Complications

Post-op care involves head elevation, cold compresses, antibiotics, and activity restrictions. Complications include hematoma, skin necrosis, nerve injury, infection, and scarring, with varying risks.

Primary Contributor: Dr Benedetta Agnelli, Educational Fellow

Verified by thePlasticsFella ✅

Overview of Facelift

Facelift or rhytidectomy, addresses facial aging by lifting and repositioning the SMAS and soft tissues to improve midface, jawline, and neck definition.

Facelift surgery (rhytidectomy) rejuvenates facial contours by repositioning deep tissues and removing or redraping excess skin to correct laxity, soft tissue descent, and volume changes. It has the ability to,

- Enhance the jawline.

- Reduce nasolabial folds.

- Lift the midface and neck.

Techniques have progressed from simple skin excisions to advanced multilayered methods targeting the SMAS, deep fat compartments, and retaining ligaments.

Described by Mitz and Peyronie in 1976, the SMAS revolutionized the approach to facelift - though its anatomical distinctness remains debated (Minelli et al., 2023).

Relevant Anatomy for Facelift

The SMAS is the key layer in facelift surgery, surrounding the mimetic muscles, while the facial nerve (CN VII) and retaining ligaments are critical landmarks, with the nerve requiring careful preservation.

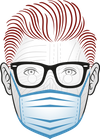

The soft tissues of the face are organized in concentric layers, similar to the scalp. The five anatomic layers are (Mendelson, 2002),

- Layer 1: Skin.

- Layer 2: Subcutaneous fat.

- Layer 3: Superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS).

- Layer 4: Loose areolar tissue (contains retaining ligaments + glide planes).

- Layer 5: Deep fascia.

The image below illustrates these five soft tissue layers of the face.

SMAS

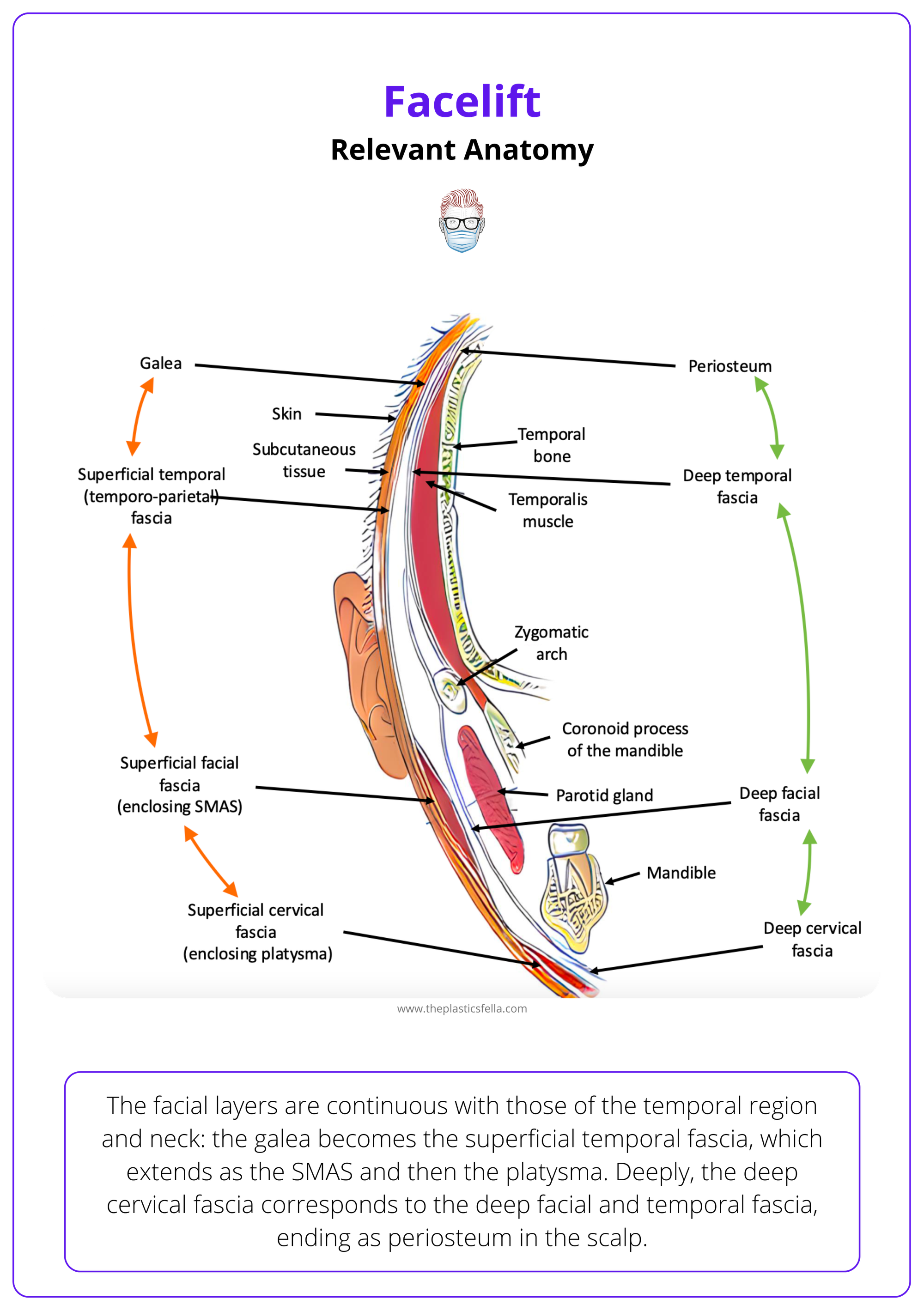

The SMAS (layer 3) is the key layer for facelift procedures. It invests the mimetic muscles and is continuous with the platysma muscle inferiorly and the temporoparietal fascia and galea aponeurotica superiorly. It can be divided into two main portions.

- Fixed Lateral SMAS: Tightly adherent to the parotid gland.

- Mobile Medial SMAS: Thinner and areolar in nature; easier to dissect.

The SMAS layers are illustrated below.

Areas where the SMAS is fused to the deep fascia or anchored to underlying structures are known as retaining ligaments; they function as,

- True osteocutaneous ligaments (e.g., zygomatic, mandibular)

- Fusion zones between superficial and deep fascial layers (e.g., masseteric)

Facial Nerve

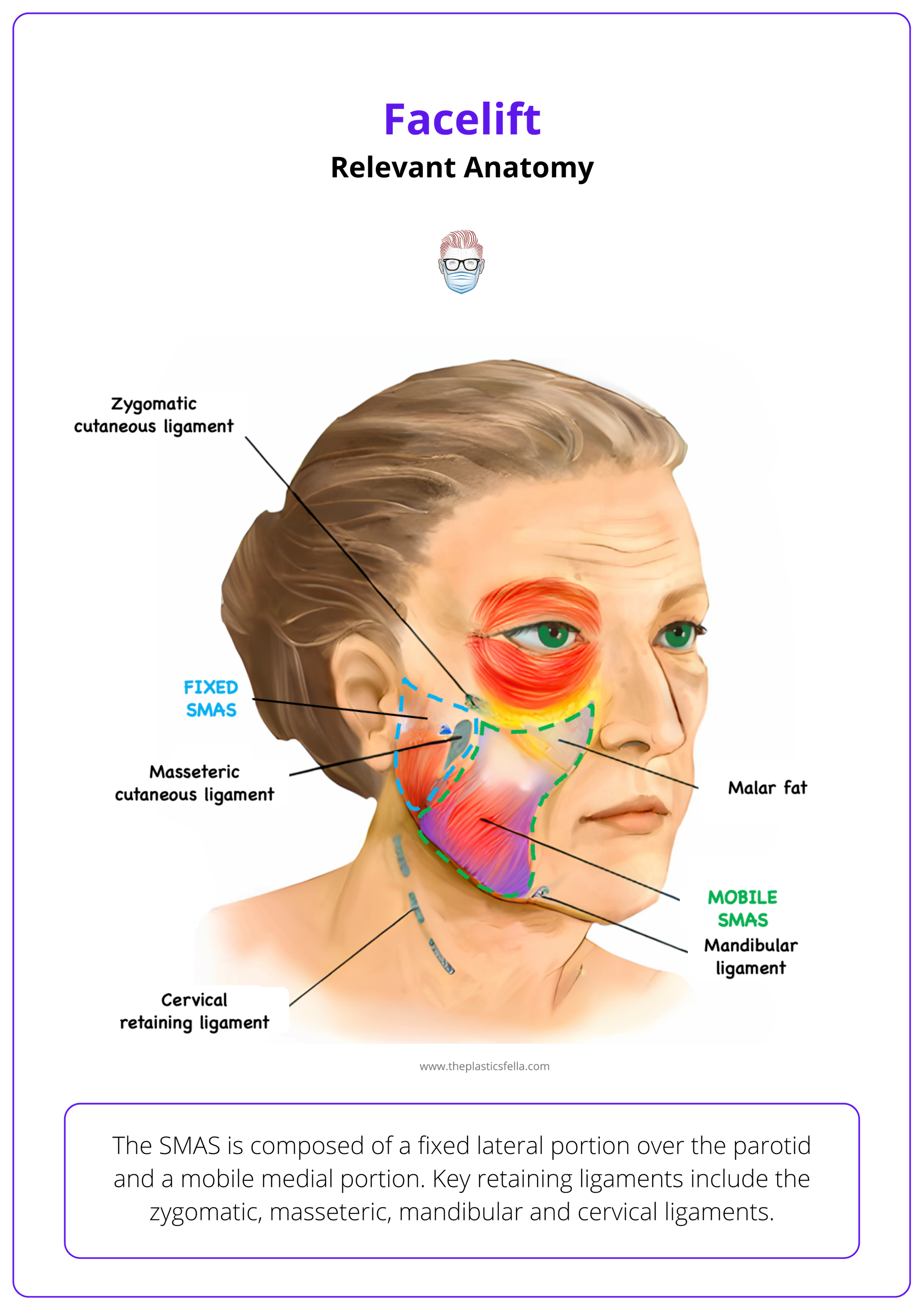

The facial nerve (CN VII) exits the stylomastoid foramen and enters the parotid gland, dividing into five branches.

- Temporal: Follows Pitanguy’s line; at risk during high-SMAS or temple dissection.

- Zygomatic

- Buccal

- Marginal Mandibular: Emerges 1–2 cm from the gonial angle; typically runs above the mandible but is vulnerable due to its superficial course.

- Cervical: Innervates platysma; enters subplatysmal plane early and is at risk during neck dissection.

Branches run deep to the parotid-masseteric fascia and enter the sub-SMAS plane to innervate muscles, except the levator anguli oris, buccinator, and mentalis, which receive superficial innervation. They remain protected deep within the retaining ligaments until those structures are released during dissection.

Crucially, facial nerve branches lie deep to the retaining ligaments, providing protection during early dissection. However, once these ligaments are released, the nerves become more superficial and increasingly vulnerable to injury (Charafeddine, 2019).

The facial nerve is illustrated below.

The frontal and marginal mandibular branches have a lower potential for functional recovery if damaged, owing to their limited interconnections with respect to other facial nerve branches.

Clinical Assessment & Indications for Facelift

A thorough assessment considers medical history, medications, prior treatments, and facial anatomy. Goals include restoring contours, volume, and tightening for a natural, refreshed appearance.

Successful facelift surgery starts with a thorough patient assessment. This includes,

History

- Detailed Medical History: Particular attention should be paid to: cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, history of bleeding disorders or poor wound healing, and smoking and alcohol use.

- Medications: Anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents, NSAIDs, corticosteroids, and herbal supplements may increase the risk of bleeding or delay healing.

- Prior Facial Treatments: Facial surgeries, injectables, or energy-based treatments may alter tissue quality and intraoperative handling, leading to increased fibrosis, reduced pliability, and unpredictable dissection planes.

Examination:

The physical exam focuses on evaluating the degree and pattern of facial aging. Key aspects include,

- Skin Quality: Texture, elasticity, photodamage.

- Soft Tissue Laxity: Midface descent, jowling, platysmal banding.

- Fat Volume: Loss in the malar area or accumulation along the jawline.

- Bone Support: Mandibular and malar projection.

- Neck Anatomy: Cervicomental angle, subplatysmal fullness.

- Dynamic Activity: Overactive depressors, facial asymmetries.

Aesthetic evaluation is conducted in both static and dynamic states, often with photographic documentation. Patients should be assessed in upright and supine positions to simulate intraoperative tissue repositioning.

The aim of a modern facelift is restoration, not transformation. Key objectives include,

- Repositioning midface and lower face ptosis.

- Restoring gonial angle, cervicomental angle, and mandibular border.

- Volumization with fat grafting or redraping, avoiding excessive skin tension.

- Tightening of the SMAS layer while maintaining a natural appearance.

- Neck contouring, when indicated, via subplatysmal or anterior approaches.

Contraindications

Certain conditions may contraindicate facelift surgery, either absolutely or relatively. These include,

- Uncontrolled Comorbidities: Hypertension, diabetes, or cardiac disease.

- Active Smoking: Increases the risk of flap necrosis and poor wound healing.

- Coagulopathy or Anticoagulants: Unless managed preoperatively.

- Psychological Instability: Body dysmorphia or unrealistic expectations.

- Prior Radiation to the Face or Neck: May impair vascularity and healing.

- Poor Skin Quality: May limit aesthetic outcomes.

Each case should be evaluated individually, with surgical planning adapted to minimize risk and optimize results.

Surgical Techniques for Facelift

Multiple facelift techniques exist, differing in dissection depth, SMAS handling, and lift vector. Ranging from skin-only to deep plane and preservation methods, each with distinct indications, risks, and outcomes.

Over the years, a variety of techniques have been developed, reflecting the evolving understanding of facial anatomy, ageing physiology, and aesthetic ideals.

Surgical approaches vary in complexity, depth of dissection, extent of SMAS manipulation, and vector of lift.

Superficial Techniques

- Skin-Only Facelift

This is the most limited form of facelift, involving only skin undermining and redraping. There is no SMAS manipulation. While the procedure is fast and associated with a short recovery, results are generally less durable and natural due to the skin bearing all the tension. Main indication is for older patients with comorbidities or those seeking minimal downtime.

- SMAS Plication

This technique involves subcutaneous dissection with folding (plicating) the SMAS using sutures without excision. It enhances midface and jawline contour without entering the deep plane, although it may not sufficiently address advanced aging or volume descent.

- SMAS Imbrication

The technique consists of incision, advancement, and overlapping SMAS with suture fixation. The cheek and neck are suspended upward and laterally without SMAS undermining. Drawbacks and advantages similar to plication.

- SMASectomy (Baker, 2001)

A strip of SMAS is excised, usually from the lateral cheek, and the edges are sutured under tension to elevate the underlying tissues. It presents the risk of contour irregularities and limited midface effect.

- Minimal Access Cranial Suspension (MACS) Facelift (Tonnard, 2007)

A variation of the plication method. Subcutaneous tissues are dissected from the underlying SMAS-platysma layer and then suspended via long looping sutures with multiple bites (microimbrication) in a vertical vector.

Deep Plane and High SMAS Techniques

- High SMAS Facelift (Barton, 1992)

Involves elevating the SMAS flap more medially, over the zygomatic eminence, allowing better control of midface volume and nasolabial fold softening. The dissection stays in the sub-SMAS plane and does not routinely involve ligamentous release. Advantages include improved midface and jowl correction with a vertical vector of lift. Although it is technically demanding, with risk of injury to the facial nerve if improperly executed.

- Deep Plane Facelift (Hamra, 1990)

Consists of sub-SMAS dissection with release of the zygomatic and upper masseteric retaining ligaments. The skin, SMAS, and malar fat pad are mobilized en bloc, which allows for a natural vector of repositioning. It offers profound and long-lasting midface and lower face rejuvenation with minimal skin tension. Presents a steep learning curve, with a higher risk of nerve injury in inexperienced hands and longer operative time.

- Lamellar High SMAS (Marten, 2008)

Presents a more extended skin flap dissection. It is based on two vectors: One for the SMAS (almost vertical) and another for the skin flap (instead diagonal/superolateral), for an optimal correction of nasolabial folds.

Subperiosteal Facelift

Introduced by Tessier, it involves dissection in a deep subperiosteal plane over the facial skeleton, primarily targeting the midface. It allows for elevation of the malar fat pad by releasing deep retaining ligaments. Its use is limited due to technical complexity, risk of nerve injury, and minimal impact on the lower face and neck.

Composite Facelift

The composite facelift, also developed by Hamra, extends the deep plane dissection to include the orbicularis oculi muscle, elevating it in continuity with the SMAS. This allows for superior rejuvenation of the periorbital and malar regions, effectively treating tear trough deformity and eyelid-cheek junction descent.

Preservation Facelift

Initially described by Gordon, this technique combines limited subcutaneous delamination with strategic release of retaining ligaments, allowing the mobilization of a composite SMAS flap with preserved anatomical integrity and improved biomechanical properties.

By avoiding wide subcutaneous undermining, the preservation facelift offers several theoretical advantages: reduced risk of vascular compromise, shorter recovery times, and maintenance of native fat compartments and ligamentous architecture, which may contribute to a more natural and long-lasting result, particularly in younger patients or those with favourable soft tissue tone.

Endoscopic Facelift

The endoscopic facelift represents a minimally invasive approach to facial rejuvenation, primarily applied to the upper third of the face, particularly in endoscopic brow lifting. More advanced applications have extended endoscopic techniques to the midface, allowing mobilization of the malar fat pad and orbicularis oculi complex through subperiosteal dissection.

Key advantages include reduced incision length and quicker recovery compared to open techniques. However, outcomes may be more modest; the technique requires significant expertise, and it is indicated only for patients with minimal skin excess.

These facelift techniques are summarised below.

Post Operative Care & Complications of Facelift

Post-op care involves head elevation, cold compresses, antibiotics, and activity restrictions; complications include hematoma, skin necrosis, nerve injury, infection, and scarring, with risks varying by surgical plane.

Post-operative management is essential to optimize healing, reduce complications, and ensure patient satisfaction. Standard care protocols include,

- Head elevation and rest.

- Cold compresses during the first 48 h can reduce swelling and bruising.

- Antibiotics, short-term prophylactic to prevent infection.

- Drains may be applied.

- Activity restrictions for at least 3–4 weeks.

- Follow-up.

Complications

- Hematoma (1.9–3%): The most common complication, typically within the first 24 h. It requires prompt evacuation to prevent flap compromise.

- Skin Necrosis (~1%): More common in smokers or where excessive tension is applied to the skin.

- Facial Nerve Injury: Transient facial nerve weakness is relatively common, especially with deep plane procedures. Instead, permanent injury is rare.

- Asymmetries or Recurrence (3.9%): Revisions are sometimes required due to asymmetry, recurrence of skin laxity, or dissatisfaction with the results.

- Infection: Although rare, infection can occur. Early signs include fever, redness, and swelling. Prophylactic antibiotics help mitigate the risk.

- Scarring: While most scars heal well, they can be hypertrophic in some cases, especially if the patient has a history of poor scarring.

The complications of facelift, along with the associated techniques, are summarised below.

To differentiate a cervical branch injury from a Marginal Mandibular Nerve (MMN) injury, ask the patient to pucker or evert the lower lip; if eversion is possible, the MMN is intact.

Conclusion

1. Overview: Facelift surgery repositions facial soft tissues to correct aging-related descent, improving jawline, midface, and neck contour. It’s a key procedure in facial rejuvenation, often combined with fat grafting or blepharoplasty.

2. Relevant Anatomy: Understanding the SMAS, facial nerve branches, retaining ligaments, and the transition from fixed to mobile SMAS is essential for safe and effective dissection.

3. Preoperative Assessment & Indications: Candidates present with ptosis, jowling, and neck laxity. Assessment includes skin quality, facial volume, and expectations. Planning defines dissection plane, lift vector, and combined procedures.

4. Surgical Techniques: Techniques range from skin-only to deep plane and high SMAS. Deep approaches lift the SMAS-malar complex en bloc, offering more natural and lasting results. Most recent techniques include composite facelift, preservation facelift and endoscopic techniques. 5.

5. Postoperative Care & Complications: Head elevation, limited activity, and antibiotics reduce risks. Complications include hematoma, nerve injury, skin necrosis, asymmetry, and scarring.

Further Reading

- Mendelson BC, Muzaffar AR, Adams WP Jr. Surgical anatomy of the midcheek and malar mounds. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002 Sep 1;110(3):885-96; discussion 897-911. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200209010-00026. PMID: 12172155.

- Mitz V, Peyronie M. The superficial musculo-aponeurotic system (SMAS) in the parotid and cheek area. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976 Jul;58(1):80-8. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197607000-00013. PMID: 935283.

- Minelli L, van der Lei B, Mendelson BC. The Superficial Musculoaponeurotic System: Does It Really Exist as an Anatomical Entity? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2024 May 1;153(5):1023-1034. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000010557. Epub 2023 Apr 11. PMID: 37039509; PMCID: PMC11027987.

- Charafeddine AH, Drake R, McBride J, Zins JE. Facelift: History and Anatomy. Clin Plast Surg. 2019 Oct;46(4):505-513. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2019.05.001. Epub 2019 Jul 17. PMID: 31514803.

- Alghoul M, Bitik O, McBride J, Zins JE. Relationship of the zygomatic facial nerve to the retaining ligaments of the face: the Sub-SMAS danger zone. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013 Feb;131(2):245e-252e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182789c5c. PMID: 23358020.

- Barton FE Jr. Rhytidectomy and the nasolabial fold. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992 Oct;90(4):601-7. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199210000-00008. PMID: 1409995.

- Hamra ST. Composite rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992 Jul;90(1):1-13. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199207000-00001. PMID: 1615067.

- Hamra ST. The deep-plane rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990 Jul;86(1):53-61; discussion 62-3. PMID: 2359803.

- Tonnard P, Verpaele A. The MACS-lift short scar rhytidectomy. Aesthet Surg J. 2007 Mar-Apr;27(2):188-98. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2007.01.008. PMID: 19341646.

- Baker DC. Minimal incision rhytidectomy (short scar face lift) with lateral SMASectomy: evolution and application. Aesthet Surg J. 2001 Jan;21(1):14-26. doi: 10.1067/maj.2001.113557. PMID: 19331867.

- Marten TJ. High SMAS facelift: combined single flap lifting of the jawline, cheek, and midface. Clin Plast Surg. 2008 Oct;35(4):569-603, vi-vii. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2008.04.002. PMID: 18922311.

- Gordon NA, Sawan TG. Deep-Plane Rhytidectomy: Pearls in Maximizing Outcomes while Minimizing Recovery. Facial Plast Surg. 2025 Feb;41(1):2-11. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-1777312. Epub 2023 Dec 4. Erratum in: Facial Plast Surg. 2025 Feb;41(1):e1. doi: 10.1055/s-0044-1779261. PMID: 38049109.

- Tessier P. Le lifting facial sous-périosté [Subperiosteal face-lift]. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 1989;34(3):193-7. French. PMID: 2473674.

- Roskies M, Bray D, Gordon NA, Gualdi A, Nayak LM, Talei B. Limited Delamination Modifications to the Extended Deep Plane Rhytidectomy: An Anatomical Basis for Improved Outcomes. Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. 2024 Nov-Dec;26(6):657-664. doi: 10.1089/fpsam.2024.0018. Epub 2024 Jul 29. PMID: 39072376.

- Botti G, Botti C, Cella A, Gualdi A. Correction of the naso-jugal groove. Orbit. 2007 Sep;26(3):193-202. doi: 10.1080/01676830701539430. PMID: 17891647.