Summary Card

Overview

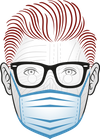

The abdominal wall, divided into anterolateral and posterior, supports and protects abdominal organs, facilitates trunk movement, and adjusts to visceral volume changes and pressure.

Surface Anatomy

Divided into quadrants and regions using palpable landmarks such as the linea alba, umbilicus (T10), and inguinal ligament (L1).

Skeletal Structure

The abdominal wall is bounded superiorly by the thoracic cage, posteriorly by the lumbar vertebrae, and inferiorly by the pelvic brim.

Layers and Musculature

Includes 5 paired anterolateral muscles. Critical surgical landmarks include the neurovascular plane (between internal oblique and transversus abdominis) and arcuate line. Knowledge of vascular supply (e.g., DIEA for flaps) is essential for safe dissection.

Clinical Significance

Vital for flap harvest (e.g., TRAM, DIEP, SIEA), hernia repair, and component separation techniques (CST). Direct hernias = medial to inferior epigastric vessels (via Hesselbach’s triangle). Indirect hernias = lateral to vessels (congenital path)

Primary Contributor: Dr Carissa J. Jacobs

Verified by thePlasticsFella ✅

Overview of Abdominal Wall Anatomy

The abdominal wall, divided into anterolateral and posterior regions, supports and protects abdominal organs, enables trunk movement, and adjusts to changes in intra-abdominal volume and pressure.

The abdominal wall forms the boundary of the abdominal cavity and is anatomically divided into two key sections.

- Anterolateral abdominal wall

- Posterior abdominal wall

It extends from the thoracic cage superiorly to the pelvic bones inferiorly, enclosing the abdominal contents and contributing to core function.

Unlike the thorax and pelvis, the abdominal wall lacks a complete bony framework, which allows it to accommodate changes in intra-abdominal volume. For example, during digestion, respiration, and pregnancy. It also stabilizes the spine and facilitates trunk motion.

Functionally, the abdominal wall plays a crucial role in essential physiological processes by increasing intra-abdominal and intrathoracic pressure through muscular contraction. This action supports:

- Expulsion of air (e.g., coughing, sneezing)

- Emesis (vomiting)

- Defecation

- Micturition

- Parturition

Plastic surgeons commonly harvest flaps from the abdominal wall for reconstructive procedures (especially breast reconstruction) and are often involved in complex abdominal wall repairs. These flaps vary by vascular supply, tissue composition, and anatomical origin. Accordingly, a solid grasp of abdominal wall anatomy is fundamental for,

- Flap design and elevation.

- Ensuring vascular reliability.

- Avoiding functional deficits or complications during reconstruction.

In states of increased respiratory demand, whether due to exercise, illness, or stress, the anterolateral abdominal muscles act as accessory expiratory muscles, aiding active exhalation by depressing the rib cage.

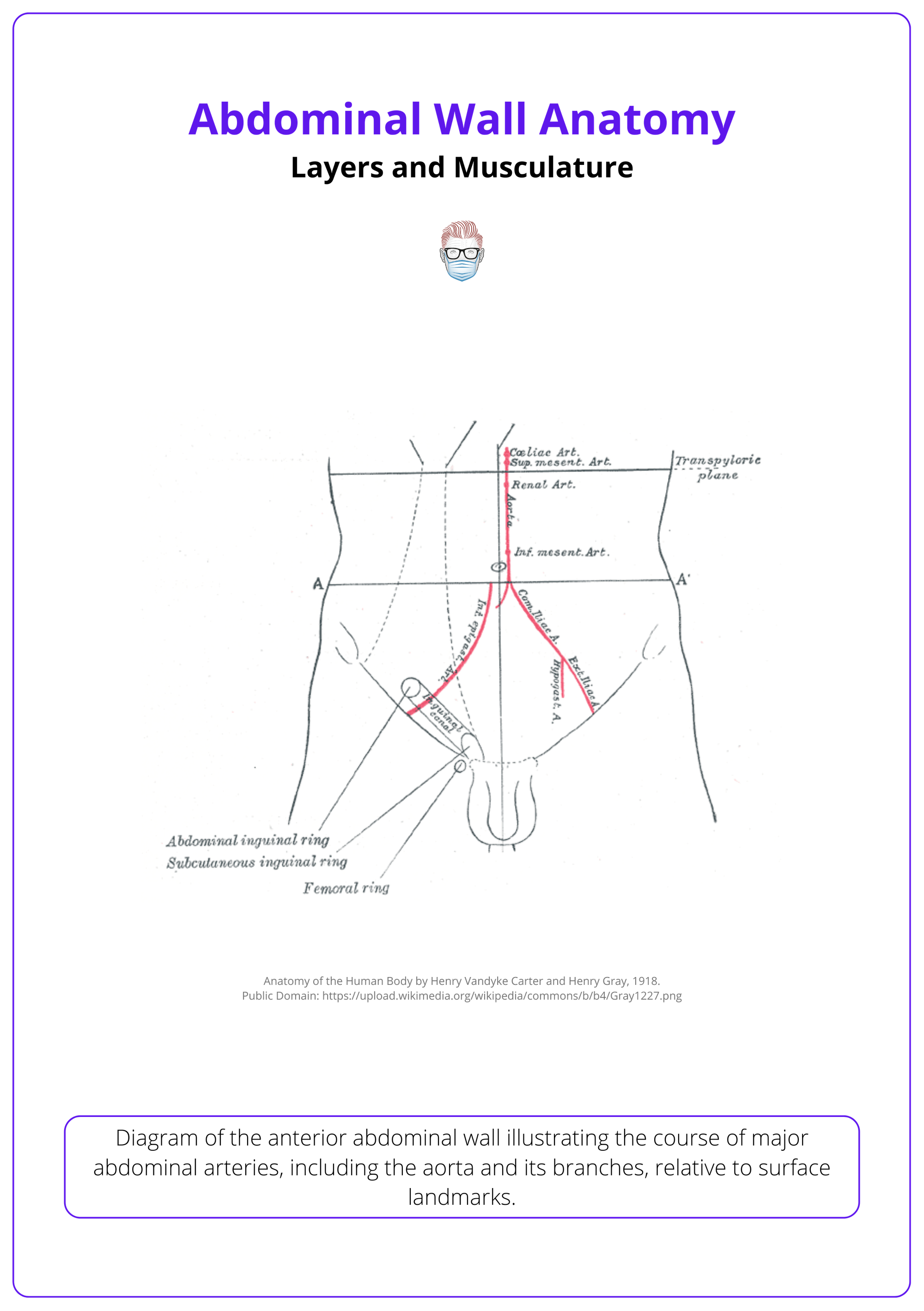

The anterior abdominal wall is illustrated below.

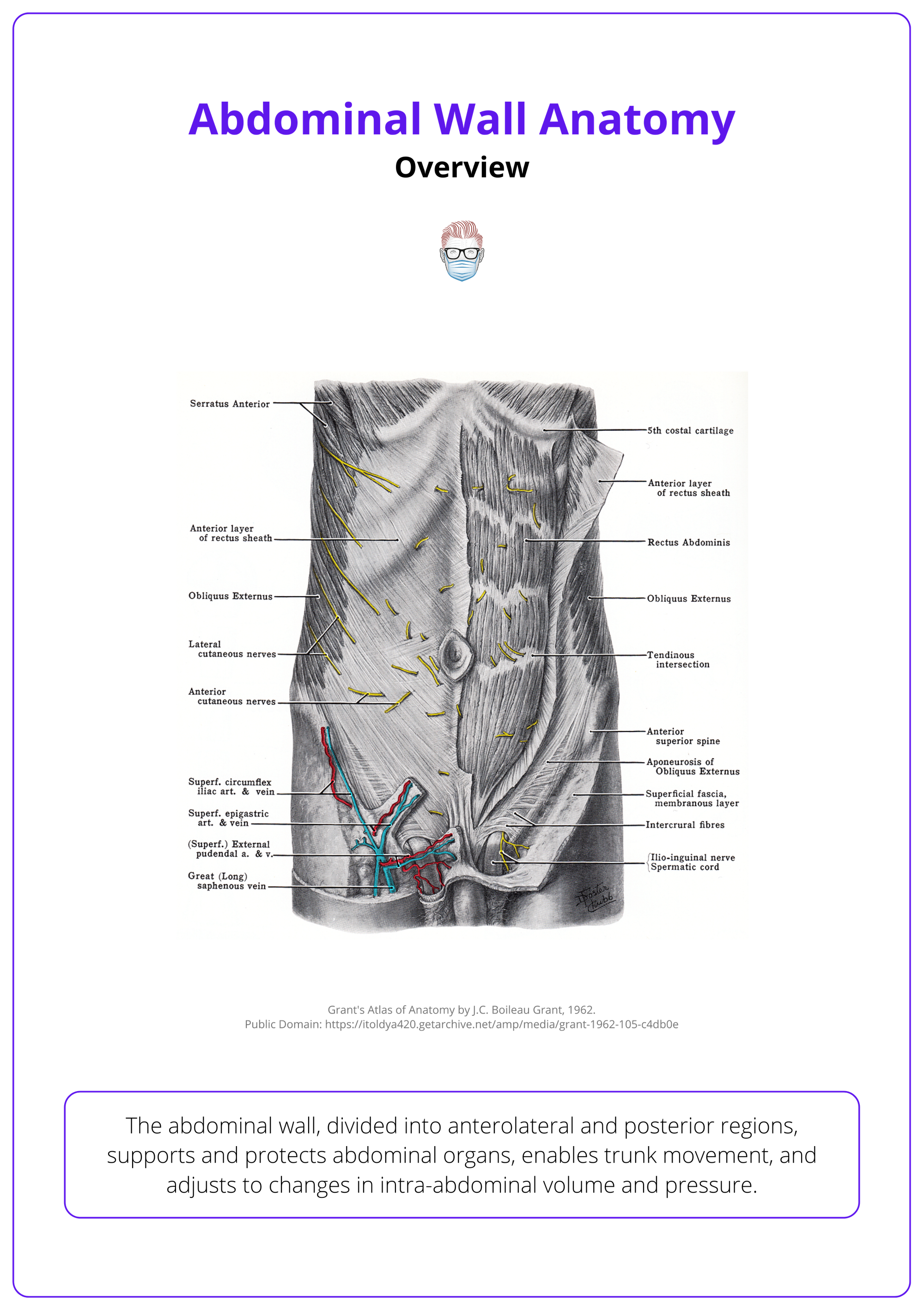

The posterior abdominal wall is illustrated below.

Embryology

The abdominal wall forms through lateral folding of the embryonic disc, with contributions from mesoderm and ectoderm.

- Around week 4 of gestation, the trilaminar embryonic disc folds laterally, fusing the left and right body walls at the midline.

- Mesoderm forms the muscles and connective tissue; ectoderm forms the skin.

- Somites (paraxial mesoderm) differentiate into myotomes, which become abdominal wall muscles.

- Ventral body wall closure is completed by week 6.

- Failure results in congenital defects such as omphalocele or gastroschisis.

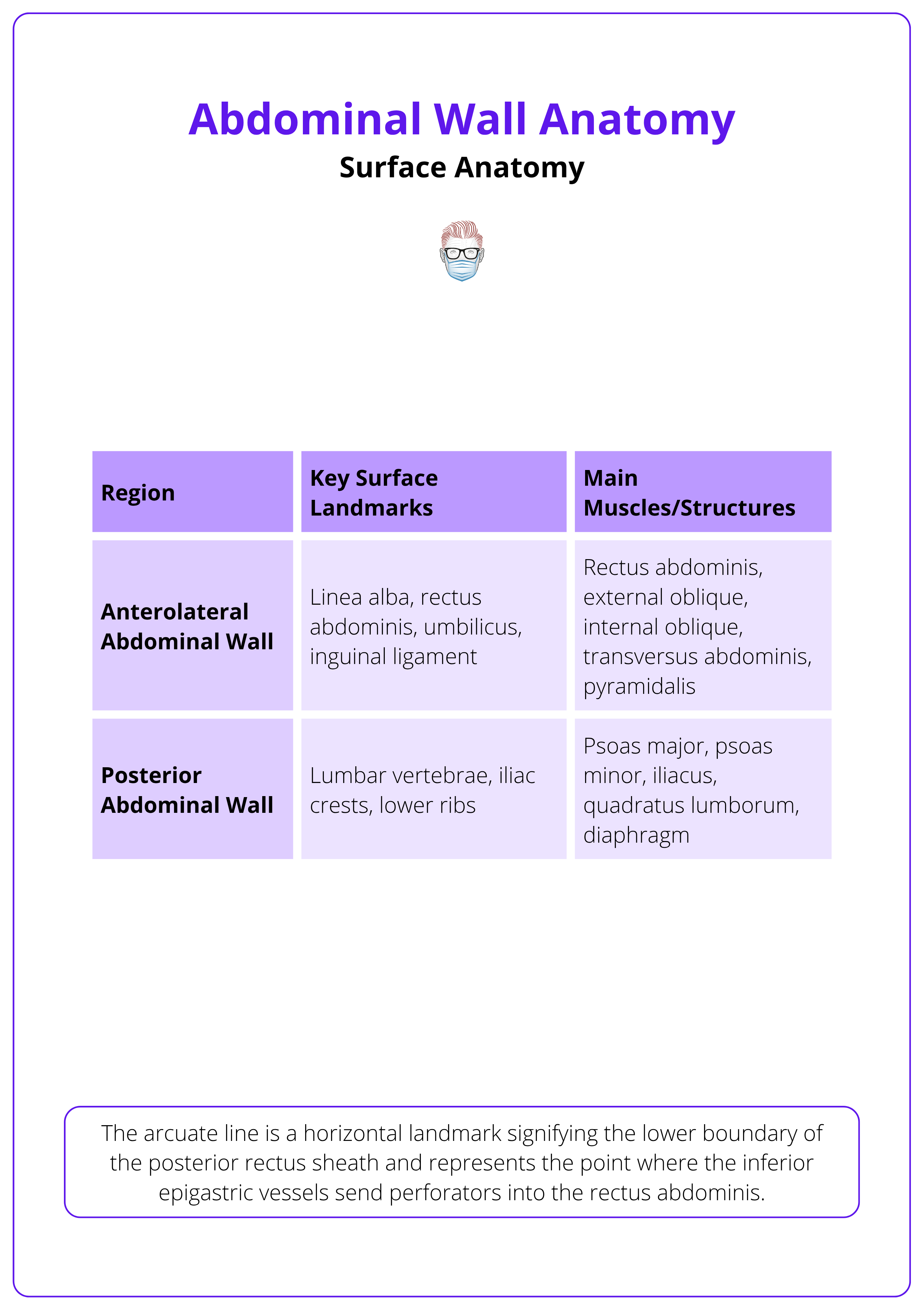

Surface Anatomy of the Abdominal Wall

The arcuate line is a horizontal landmark signifying the lower boundary of the posterior rectus sheath and represents the point where the inferior epigastric vessels send perforators into the rectus abdominis.

the cal and horizontal planes. The nine regions are: epigastric, umbilical, and hypogastric in the midline, and paired left and right hypochondriac, lumbar, and iliac regions. There are a number of important surface landmarks on the anterior abdomen.

- The Linea Alba: A midline fibrous structure running from the xiphoid process to the pubic symphysis.

- Rectus Abdominis: Palpable as paired vertical muscles on either side of the linea alba.

- Rectus Sheath: Encloses the rectus abdominis and is divided into anterior and posterior layers, with the posterior layer ending at the arcuate line (about midway between the umbilicus and pubic symphysis).

- Linea Semilunaris: A paired vertical fibrous structure that runs along the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis.

An important distinction occurs above and below the arcuate line.

- Above the Arcuate Line: The posterior rectus sheath is composed of aponeuroses from the internal oblique (posterior layer) and transversus abdominis muscles.

- Below the Arcuate Line: All aponeurotic fibres (from external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis) pass anterior to the rectus abdominis, leaving only transversalis fascia and peritoneum behind it.

Additional landmarks include,

- Umbilicus: Located at the level of the L3–L4 vertebrae, serving as a central surface landmark. The umbilical dermatome corresponds to T10, a key surface marker commonly used in trauma and neurological assessment. Other important dermatomal landmarks include T4 at the nipple line and L1 at the inguinal ligament.

- Inguinal Ligament: Runs from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the pubic tubercle, marking the lower border of the abdominal wall.

The posterior abdominal wall is located at the back of the abdomen, extending from the 12th rib and lumbar vertebrae down to the iliac crests and sacrum. The surface anatomy is less distinct than the anterolateral wall. The posterior wall forms the boundary between the abdominal cavity and the intrinsic muscles of the back, providing protection and support for retroperitoneal organs.

These key regions, their landmarks, and main structures are summarised below.

The anterior trunk is illustrated below.

Skeletal Structure of the Abdominal Wall

The abdominal wall is bounded superiorly by the thoracic cage, posteriorly by the lumbar vertebrae, and inferiorly by the pelvic brim.

The skeletal framework of the abdominal wall provides essential structural support and serves as a scaffold for muscular and fascial attachments. The boundaries can be described as follows.

Superiorly

- Inferior Ribs (7th–12th ribs): Provide attachment for the external oblique and transversus abdominis.

- Costal Cartilages: Contribute to the costal margin.

- Xiphoid Process of the Sternum: Serves as an attachment point for the rectus abdominis and the linea alba.

Posteriorly

- Lumbar Vertebrae (L1–L5): Provide major support for the posterior abdominal wall. Psoas major, quadratus lumborum, and iliacus originate or insert here.

- 12th Rib: Anchors the quadratus lumborum and transversus abdominis.

Inferiorly

- Iliac Crest: Attachment site for the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis.

- Anterior Superior Iliac Spine (ASIS): Serves as a landmark and origin for the inguinal ligament.

- Pubic Symphysis and Pubic Crest: Inferior attachment for rectus abdominis and insertion for the pyramidalis muscle.

- Inguinal Ligament: A fibrous band from the ASIS to the pubic tubercle, acting as a key landmark in lower abdominal anatomy and hernia surgery.

Bones of the abdominal wall are illustrated below.

Layers and Musculature of Abdominal Wall Anatomy

There are 5 paired muscles in the anterolateral abdominal wall and 4 paired muscles in the posterior abdominal wall and the diaphragm.

Understanding the muscular and fascial structure of the abdominal wall is critical in both flap harvest and reconstruction. Anatomical precision enables safe dissection, preservation of perfusion, and reduction of complications such as necrosis, donor site morbidity, and functional loss.

Clinical Applications of Flaps

- TRAM (Transverse Rectus Abdominis Myocutaneous) Flap: Involves the rectus abdominis and overlying skin/fat. Knowledge of the rectus sheath, perforators, and vascular zones is vital.

- DIEP (Deep Inferior Epigastric Perforator) Flap: Muscle-sparing; requires familiarity with intramuscular perforator anatomy.

- SIEA (Superficial Inferior Epigastric Artery) Flap: Less invasive, based on superficial vasculature; anatomy is variable.

- VRAM (Vertical Rectus Abdominis Myocutaneous) Flap: Useful in pelvic or perineal reconstruction; based on the superior epigastric artery.

Abdominal Wall Reconstruction

In trauma, hernia, or tissue defects, layer restoration is essential. Surgeons may employ,

- Component separation to mobilize muscle layers.

- Mesh (prosthetic or biologic) in appropriate fascial planes.

- Flaps to restore function and form.

Muscle-sparing techniques (e.g. DIEP over TRAM) preserve abdominal wall strength and reduce hernia risk.

- Neurovascular Plane

- Intercostal nerves and vessels run between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles, forming the neurovascular plane.

- This anatomical space is the target of the Transversus Abdominis Plane (TAP) block, a regional anesthesia technique used for postoperative analgesia.

- Accurate identification of muscle layers is essential for safe and effective nerve blockade.

Layers of the Anterolateral Abdominal Wall (Superficial to Deep)

- Skin

- Subcutaneous tissue

- Muscles, investing fascia, and aponeuroses

- Transversalis fascia

- Extraperitoneal fat

- Parietal peritoneum

The subcutaneous tissue has two layers.

- Camper’s Fascia: Superficial fatty layer.

- Scarpa’s Fascia: Deeper membranous layer.

Muscles of the Anterolateral Abdominal Wall (5 paired)

- External oblique.

- Internal oblique.

- Transversus abdominis.

- Rectus abdominis.

- Pyramidalis (present in ~80% of people).

The table below summarises the origin, insertion, vascular supply, and clinical relevance of the key muscles that form the anterolateral abdominal wall.

The rectus abdominis muscle, known for forming the "six-pack," actually varies in the number of tendinous intersections. Some people naturally have four, eight, or even ten-pack abs depending on their genetics.

Muscles of the Posterior Abdominal Wall (4 paired + diaphragm)

- Psoas major

- Iliacus

- Quadratus lumborum

- Psoas minor (present in ~40% of people)

A cross-section of the abdominal wall is illustrated below.

The Inguinal Triangle and Inguinal Canal

Boundaries of Hesselbach’s Triangle

- Medial: Lateral border of rectus abdominis.

- Anterolateral: Inferior epigastric vessels.

- Inferoposterior: Inguinal ligament.

Hesselbach’s Triangle

- Located within the anterior abdominal wall, Hesselbach’s triangle is a key anatomical region and a common site for direct inguinal hernias, which pass medial to the inferior epigastric vessels — a distinction important in clinical examinations.

- In contrast, indirect inguinal hernias are congenital and pass lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels through the deep inguinal ring.

- Hesselbach’s triangle also holds surgical relevance during lower abdominal flap harvests such as the TRAM or DIEP flap, where careful dissection is required near or within this area.

Frank Hesselbach, a German anatomist, first described this triangle in 1806.

The vascular anatomy of the DIEP flap is centered on the deep inferior epigastric artery (DIEA), which arises from the external iliac artery. It traverses deep to the transversalis fascia and then passes superficially to the arcuate line to supply the anterior rectus sheath through perforators.

Hesselbach’s triangle is illustrated below.

Anatomical Boundaries of the Inguinal Canal

- Anterior: External oblique aponeurosis (reinforced by internal oblique laterally).

- Posterior: Transversalis fascia, conjoint tendon.

- Roof: Transversalis fascia, internal oblique, transversus abdominis.

- Floor: Inguinal ligament (from external oblique aponeurosis), lacunar ligament.

The inguinal canal runs inferiorly and medially through the lower abdominal wall, just above and parallel to the inguinal ligament. It acts as a conduit for structures passing between the abdominal cavity and the external genitalia. Clinically, it is another vulnerable point in the abdominal wall and is a frequent site for indirect inguinal hernias.

The inguinal canal is illustrated below.

Conclusion

1. Overview: The abdominal wall plays a vital dynamic role beyond structural support, contributing to organ protection, trunk stability, and physiological functions such as respiration, pressure regulation, and visceral accommodation. It can be subdivided into anterolateral and posterior.

2. Embryology: Proper embryological development of the abdominal wall is characterised by lateral folding, mesodermal differentiation, and ventral closure. It is essential for forming the muscular structure and preventing congenital defects.

3. Surface Anatomy: The anterolateral abdominal wall spans the front and sides of the abdomen and is divided into regions using palpable landmarks and lines relevant for clinical examination. The posterior abdominal wall protects the retroperitoneal organs and lies deep to the intrinsic muscles of the back.

4. Skeletal Structure: The ribs, vertebrae, and pelvis provides structural support and attachment sites for muscles.

5. Layers and Musculature: A thorough understanding of the muscle layers, fascial planes, and vascular supply, is essential for designing safe, functional flaps and performing effective abdominal wall reconstruction with minimal morbidity.

6. The Inguinal Triangle and Inguinal Canal: Hesselbach’s triangle is clinically significant because of its association with hernias, its proximity to critical vascular structures, and thus its relevance during lower abdominal flap harvest and reconstruction.

7. Clinical Significance: Anatomical knowledge guides surgical incisions, flap design, component separation, and hernia repair, directly impacting patient outcomes in terms of function, aesthetics, and complication rates.

Further Reading

- Gray H. Anatomy of the human body. 20th ed. 1918.

- Flynn W, Vickerton P. Anatomy, abdomen and pelvis: abdominal wall [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. [Updated 2023 Jul 24].

- Hope WW, Abdul W, Winters R. Abdominal wall reconstruction [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. [Updated 2023 Jul 24].

- Lopez-Monclus J, Muñoz-Rodríguez J, San Miguel C, Robin A, Blazquez LA, Pérez-Flecha M, et al. Combining anterior and posterior component separation for extreme cases of abdominal wall reconstruction. Hernia. 2020 Apr;24(2):369–379. doi: 10.1007/s10029-020-02152-3. Epub 2020 Mar 5. Erratum in: Hernia. 2021 Feb;25(1):251. doi: 10.1007/s10029-020-02343-y. PMID: 32140964; PMCID: PMC7674336.

- Stylianides N, Slade DAJ. Abdominal wall reconstruction. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2016 Mar;77(3):151–156. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2016.77.3.151.

- Laguna Hernández P, Díaz Pedrero R, Córdova García D, Alvarado Hurtado R, Allaoua Mouissaoui Y, Bru Aparicio M, et al. The importance of anatomical study of abdominal wall for general surgeons: a transversus abdominis release (TAR) eventroplasty serie. Br J Surg. 2024 May;111(Suppl_5):znae122.356. doi: 10.1093/bjs/znae122.356.

- Nunn JF, Khan YS. Anatomy, abdomen and pelvis, posterior abdominal wall nerves [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. [Updated 2022 Oct 24].

- Bissell MB, Greenspun DT, Levine J, Rahal W, Al-Dhamin A, AlKhawaji A, et al. The lumbar artery perforator flap: 3-dimensional anatomical study and clinical applications. Ann Plast Surg. 2016 Oct;77(4):469–476. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000646. PMID: 26545217.

- Heller L, McNichols CH, Ramirez OM. Component separations. Semin Plast Surg. 2012 Feb;26(1):25–28. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1302462. PMID: 23372455; PMCID: PMC3348738.

- Shokrollahi K, Whitaker IS, Nahai F. Flaps: practical reconstructive surgery. 1st ed. 2017. p. 184–209, 405–416, 502–524.

- Thieme. Atlas of anatomy. 2nd ed. p. 132–143.

- Grant JCB. Grant's atlas of anatomy. 1962.

- Mast BA. Plastic surgery. 1st ed. New York: Thieme; 2021. p. 30–39, 412–420.

- Elsevier. Gray’s anatomy for students. 3rd ed. Chapter 4.