Summary Card

Overview

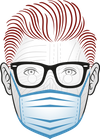

Frostbite (coldburn) is a freezing cold injury caused by prolonged exposure to subzero temperatures, where tissue heat loss exceeds local perfusion, leading to cellular freezing and damage.

Causes

The rate of tissue cooling and whether ice crystals form determine the type of cold injury. Heat loss occurs through evaporation, conduction, convection, and radiation.

Pathogenesis

Cold injuries result from direct cellular and vascular damage caused by extreme cold exposure, with intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors increasing susceptibility.

Clinical Presentation

Early recognition of deep frostbite, particularly the presence of hemorrhagic blisters, hard skin, or delayed capillary refill, is critical for initiating advanced imaging and interventions like thrombolysis.

Treatment

Timely frostbite treatment hinges on rapid rewarming, pain control, and wound care. Surgical intervention should be delayed until clear tissue demarcation, typically after 4–6 weeks.

Complications

Frostbite may result in long-term complications, including infection, chronic pain, cold intolerance, neuropathy, autoamputation, and deep vein thrombosis.

Primary Contributor: Dr Waruguru Wanjau, Educational Fellow.

Verified by thePlasticsFella ✅

Overview of Cold Burns

Frostbite (coldburn) is a freezing cold injury caused by prolonged exposure to subzero temperatures, where tissue heat loss exceeds local perfusion, leading to cellular freezing and damage. Early recognition and treatment aim to preserve viable tissue and function.

Frostbite, or freezing cold injury (FCI), is tissue damage caused by exposure to extreme cold, usually below zero degrees Celsius (Basit, 2023). It develops when the body loses heat faster than blood flow can replenish it, allowing soft tissues to freeze.

The risk increases with colder temperatures and longer exposure times. (McIntosh, 2024). This is because the body loses heat in four main ways (Brown, 2023).

- Evaporation: Sweat turns to vapor, drawing heat away.

- Conduction: Direct contact with cold surfaces pulls heat out.

- Convection: Wind or water moving across the skin accelerates cooling.

- Radiation: Heat radiates directly into the colder surroundings.

When these losses exceed the body’s defenses, frostbite sets in. The rate of cooling changes the type of damage:

- Rapid freezing causes ice to form inside cells, leading to rupture and immediate cell death.

- Slow freezing leads to ice outside cells, which draws water out, causing dehydration and secondary injury

The image below illustrates frostbite of the feet.

Causes of Cold Burns

The rate of tissue cooling and whether ice crystals form determine the type of cold injury. Heat loss occurs through evaporation, conduction, convection, and radiation.

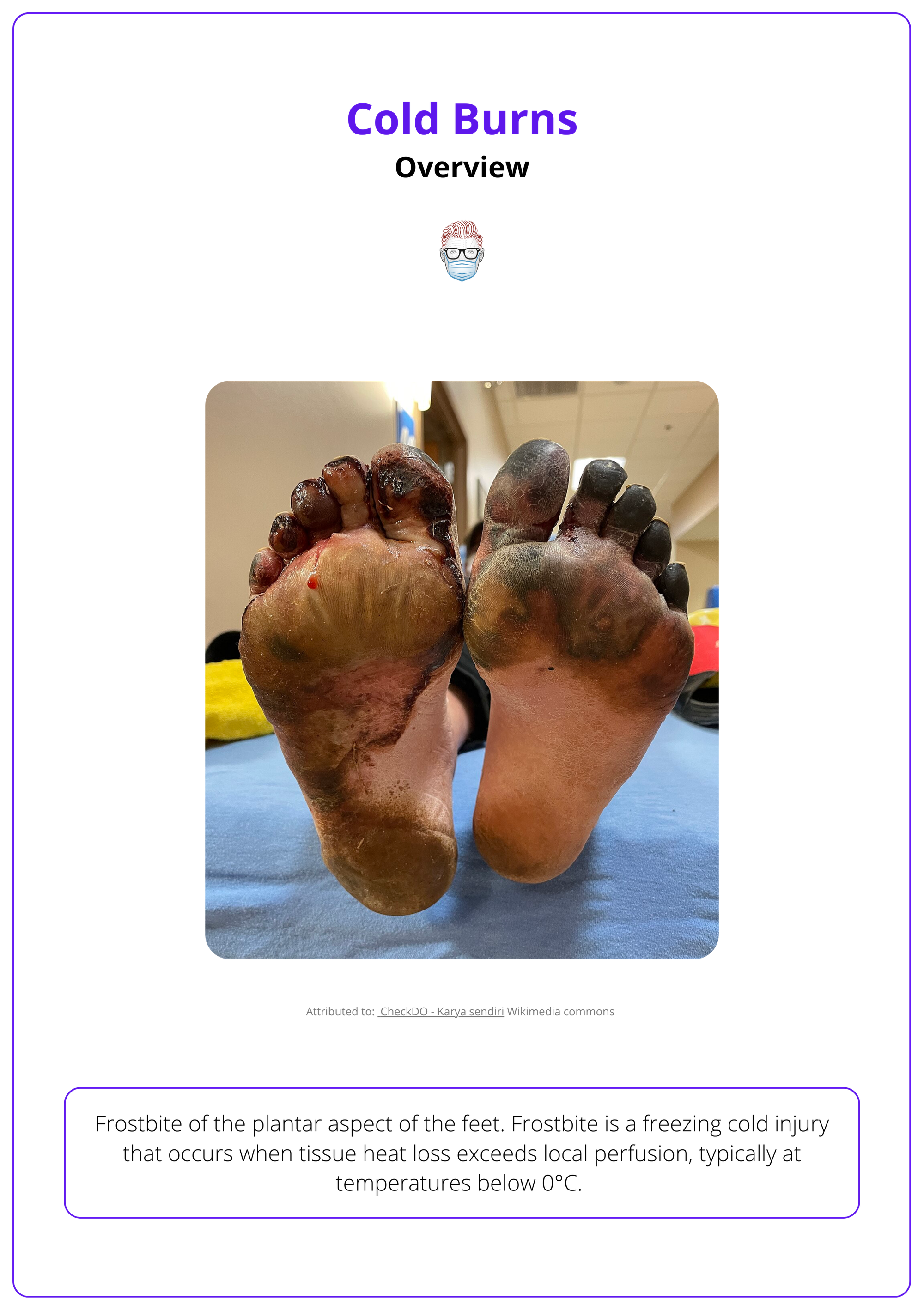

Cold injuries occur when heat loss exceeds the body’s ability to maintain adequate blood flow. The severity depends on how rapidly tissues cool and whether ice crystals form. Clinical presentations range from mild, reversible vasospasm to permanent tissue damage.

Classification reflects both the mechanism and severity of injury (Brown, 2023).

- Frostnip: Mild, reversible. Fast cooling, no ice crystal formation. Caused by intense vasoconstriction in exposed skin. Presents with pallor, pain, and numbness.

- Pernio/Chilblains: Nonfreezing injury caused by repeated exposure to near-freezing temperatures. Slow cooling with no ice crystals. This results in nodules or plaques with pain and pruritus.

- Flash Freeze Injury: Caused by very rapid cooling, leading to intracellular ice crystals and structural cell damage.

- Frostbite: Caused by slower cooling with ice formation within tissues, leading to vascular and cellular injury. Slow cooling with ice crystals.

Types of cold injuries associated with the cooling rate and site of ice crystals are summarised below.

Frostnip is not frostbite. It involves no ice crystal formation, and symptoms such as numbness and pallor resolve quickly with simple rewarming methods like covering the area or using warm hands. No tissue loss or long-term damage occurs (McIntosh, 2024).

Pathogenesis of Cold Burns

Cold injuries result from direct cellular and vascular damage caused by extreme cold exposure, with intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors increasing susceptibility.

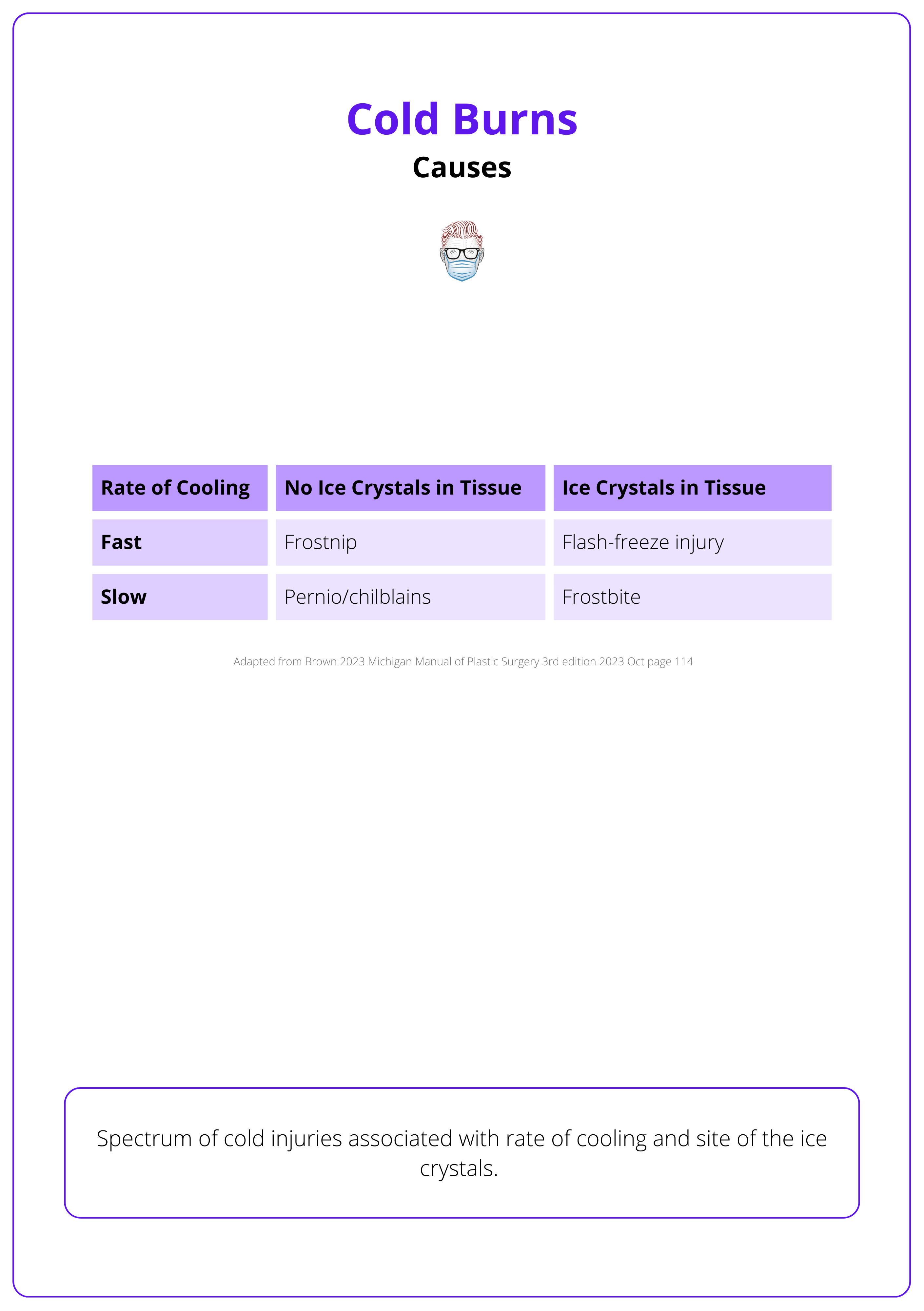

Cold burns follow a biphasic pattern of tissue injury: direct cellular damage from freezing, followed by progressive vascular impairment and ischemic necrosis.

Direct Cellular Injury (Freeze–Thaw Damage)

Tissue freezing begins around 0 °C; damaging cells through,

- Ice Crystal Formation: Intracellular and extracellular crystals physically disrupt cells.

- Intracellular Dehydration: Osmotic gradients draw water out, causing shrinkage and lysis.

- Lipid Membrane Disruption: Leads to structural collapse of cell membranes.

- Protein Denaturation: Results in irreversible functional loss of essential proteins.

Blisters will form at 6-24 hours when extravasated fluid collects beneath the detached epidermal sheet. If the dermal vascular plexus is disrupted, hemorrhagic blisters will be present.

Vascular Injury and Ischemic Necrosis

The combination of vascular stasis, inflammatory edema, and thrombotic occlusion culminates in tissue ischemia and, if severe or prolonged, cell death and necrosis. The extent of necrosis depends on exposure severity and speed of rewarming.

- Initial Vasoconstriction: Cold exposure triggers vasospasm, limiting heat delivery to extremities.

- Endothelial Damage: Increased permeability leads to edema, leukocyte infiltration, and microvascular stasis.

- Platelet Aggregation and Microthrombosis: Impair perfusion, furthering ischemic injury.

- Reperfusion Injury: On rewarming, inflammatory mediators (e.g., prostaglandins, thromboxane) cause:

- Vasodilation and Capillary Leak: Resulting in blister formation and tissue swelling.

- Continued Microthrombosis: Leading to irreversible necrosis.

The pathophysiology of frostbite can be seen below.

Normal skin perfusion is ~250 ml/min. During frostbite, this drops below 20–50 ml/min. Venous systems freeze before arteries (Basit, 2023).

Clinical Presentation of Cold Burns

Accurate classification and early recognition of deep frostbite, particularly the presence of hemorrhagic blisters, hard skin, or delayed capillary refill, are critical for initiating advanced imaging and considering interventions like thrombolysis to prevent tissue loss.

Frostbite injuries exist on a clinical spectrum and evolve over time. A structured approach starting with history, classification, and examination, followed by imaging, is essential to assess severity, predict outcomes, and guide timely treatment.

Clinical Classification Systems

Frostbite is classified to assess severity, guide management, and predict outcomes. Two main systems are used depending on the setting: a detailed four-degree classification and a simplified two-tier field classification.

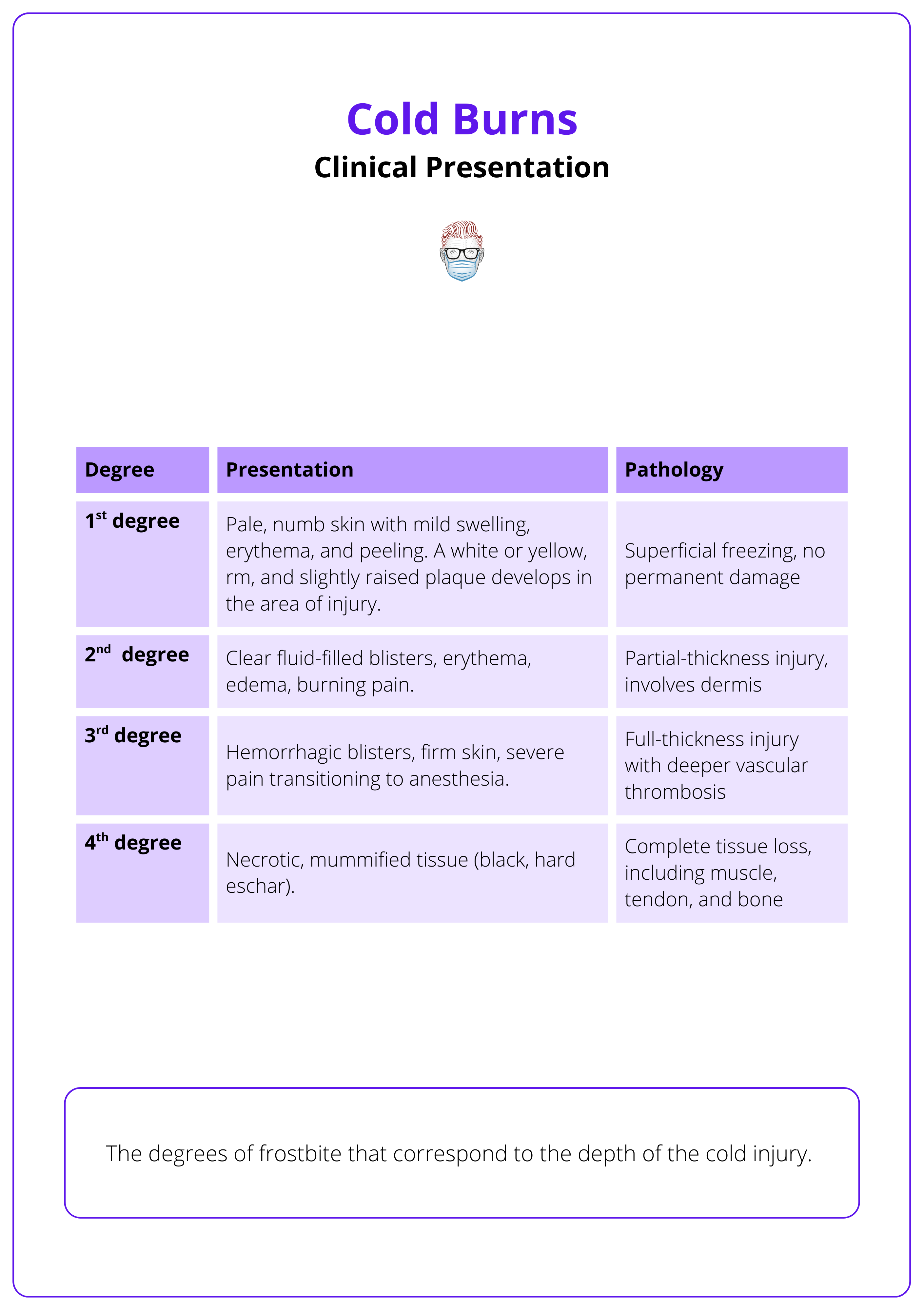

Four-Degree Classification (Clinical Use)

Mirrors burn depth and is commonly used in hospital settings.

- First-Degree (Frostnip): Reversible vasoconstriction without ice crystal formation. Pale, numb skin that fully recovers with rewarming.

- Second-Degree: Partial-thickness injury. Clear fluid-filled blisters; erythematous and swollen skin post-thaw.

- Third-Degree: Full-thickness skin and subcutaneous tissue damage. Hemorrhagic blisters may develop; tissue is anesthetic.

- Fourth-Degree: Involves muscle, tendon, and bone. Skin becomes hard, insensate; eventual mummification and autoamputation may occur.

Two-Tier Field Classification (Prehospital/Remote Settings)

Useful post-rewarming, before imaging (McIntosh 2024).

- Superficial Frostbite: Soft, pale, or waxy skin; may form clear blisters. Minimal long-term damage expected. Corresponds to 1st and 2nd degree injuries.

- Deep Frostbite: Skin is hard, woody, with hemorrhagic blisters. Suggests irreversible injury and likely tissue loss. Corresponds to 3rd and 4th degree injuries.

The clinical presentation of each degree of cold burns is summarised below.

History and Risk Factor Assessment

A comprehensive history identifies severity and contributing factors.

- Cold Exposure: Duration, temperature, wind chill, wet conditions.

- Freeze–Thaw Cycles: Multiple cycles worsen injury.

- Protective Measures: Inadequate clothing, loss of shelter.

- Medical Risk Factors: Diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, Raynaud’s, smoking.

- Behavioral and Social Factors: Substance use, mental health issues, homelessness.

- Activities: Military operations, mountaineering, and outdoor occupations.

Mnemonic Tip – The “I’s” of Frostbite (Mohr, 2009):

Intoxicated, Incompetent, Infirm, Insensate, Inducted, Inexperienced, Indigent.

Physical Examination

General Principles

- Early appearance may underestimate tissue damage.

- Final tissue demarcation may take days to weeks.

Phases of Examination

- Pre-Thaw (Early Phase)

- Skin is pale, waxy, or gray.

- Numbness or heaviness in affected areas.

- Discoloration (bluish or purplish) from vascular stasis.

- Post-Thaw (Progressive Phase)

- Swelling, pain, or anesthesia.

- Superficial Injuries: Clear blisters, erythema, preserved capillary refill.

- Deep Injuries: Hemorrhagic blisters, hard skin, absent sensation.

- Delayed Findings (Days to Weeks)

- Eschar Formation: By 10–15 days.

- Mummification and Demarcation: Develop over 3–8 weeks.

Associated Signs

- Edema within 3–5 hours post-rewarming.

- Blisters form typically 4–24 hours later.

- Severe cases may show mottled, cyanotic, or blackened skin.

Commonly Affected Areas

Cold injuries most often occur in areas with poor insulation and high exposure (Basit, 2023; Brown, 2023).

- Distal Extremities: Fingers, toes, feet, and hands.

- Exposed Skin: Nose, ears, cheeks, chin, lips.

- Genitalia: Rare, but may occur in extreme exposures.

Investigations

Imaging aids in evaluating tissue viability and planning interventions, especially in deep frostbite.

- X-ray: To detect fractures, retained foreign bodies, or trauma.

- Technetium-99m Bone Scintigraphy

- Evaluates perfusion and viability.

- Recommended between days 2–4 and repeated on day 7–8 for 2nd–4th degree frostbite (Twomey, 2005).

- Helps determine candidacy for thrombolysis or need for amputation planning.

- Doppler Ultrasound: Assesses vascular flow in superficial and deeper structures.

- MRI / CT Angiography

- Used in severe or ambiguous cases to define the extent of soft tissue and vascular injury.

- Post-thrombolytic angiography should be repeated every 12–24 hours to assess response (Zaramo, 2023).

An X-ray image of a hand frostbite is shown below.

Treatment of Cold Burns

Timely frostbite treatment hinges on rapid rewarming, pain control, and wound care; and in deep injuries, consideration of thrombolysis and vasodilators to salvage tissue. Surgical intervention should be delayed until clear tissue demarcation, typically after 4-6 weeks.

Initial and Supportive Management

Hypothermia Management (Dow, 2019)

- Mild hypothermia may be treated concurrently with frostbite.

- Moderate to severe hypothermia must be addressed before frostbite, using warmed IV fluids to restore core temperature >35 °C (Dow, 2019).

Rapid Rewarming

- Warm water immersion (37–39°C) for 15–30 minutes until erythema returns.

- Use a thermometer and regularly replace cooled water to maintain the temperature.

- Avoid temperatures >40°C to prevent thermal burns.

- Rewarm only if refreezing can be avoided, as repeat freeze–thaw cycles worsen tissue injury (McIntosh, 2024).

Watch for afterdrop — a core temperature drop from recirculating cold blood during rewarming (Brown, 2023).

Pharmacologic Interventions

Pain Control

- NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen) reduce both pain and harmful prostaglandin/thromboxane activity.

- Narcotics may be required in moderate-to-severe cases.

Wound Care

- Clear Blisters: Leave intact to reduce infection.

- Hemorrhagic Blisters: Drain to reduce pressure necrosis.

- Aloe Vera Cream: Apply every 6 hours; inhibits prostaglandins and reduces thrombosis (McCauley, 1983).

- Dressings: Use sterile, non-adherent gauze. Place cotton between digits to reduce friction (Zaramo, 2023).

Antibiotics and Tetanus

- Indicated only with open wounds, signs of infection, or concurrent trauma.

- Administer tetanus toxoid if immunization is incomplete.

Low Molecular Weight Dextran (LMWD)

- IV LMWD reduces blood viscosity and prevents microthrombi. Can be started in the field once warmed (McIntosh, 2024).

Vascular Salvage Therapies

Thrombolysis

- tPA (tissue plasminogen activator) — IV or intra-arterial — may salvage tissue in deep frostbite (Grade 3–4) when given within 24 hours.

- Consider follow-up aspirin and heparin therapy post-thrombolysis (Chung, 2024).

Vasodilator Therapy

- Iloprost (prostacyclin analog): Reduces inflammation, promotes vasodilation, inhibits platelet aggregation (Roche-Nagle, 2008).

- Other agents include prostaglandin E1, nitroglycerin, nifedipine, pentoxifylline, and reserpine (McIntosh, 2024).

Surgical Management

Surgical decisions should be deferred until necrotic tissue clearly demarcates (typically 4-6 weeks post-injury) to avoid premature loss of viable tissue.

- Debridement: Delayed to allow accurate tissue viability assessment via imaging (scintigraphy, MRI, angiography).

- Amputation: Only once mummification or necrosis is clearly established. Premature surgery risks unnecessary morbidity (Zaramo, 2023).

- Reconstructive Options: Flaps or grafts may be required for function or cosmesis.

If refreezing is a risk, do not thaw the affected tissue. Repeated freeze–thaw cycles cause greater damage than leaving the tissue frozen until continuous warming is possible (McIntosh, 2024).

Complications of Cold Burns

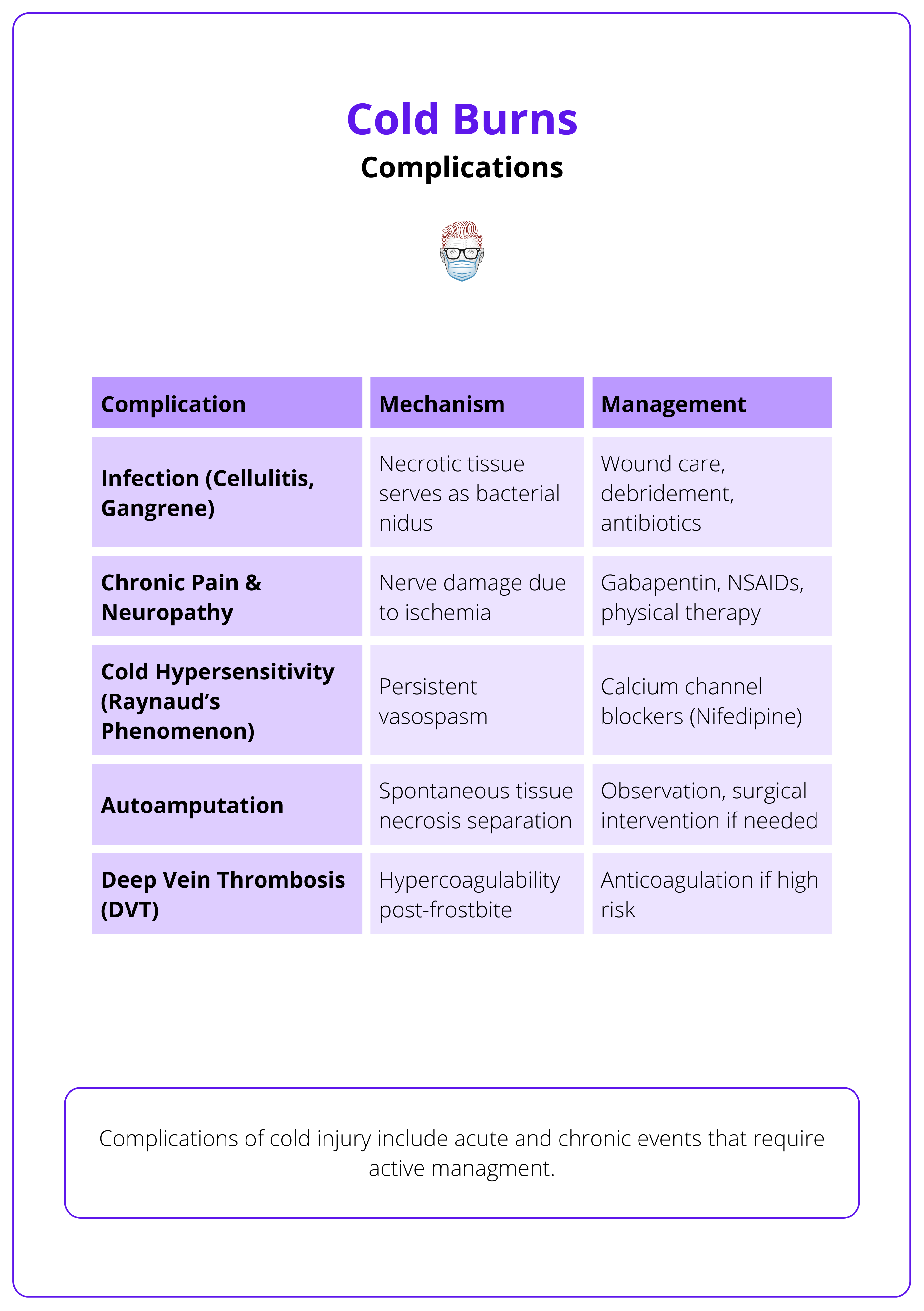

Frostbite may result in long-term complications, including infection, chronic pain, cold intolerance, neuropathy, autoamputation, and deep vein thrombosis.

Cold burn patients may have an intolerance to cold in previously frostbitten areas, which may be a consequence of vasospasm and abnormal autonomic tone following cold injury. Complications from cold burns include local tissue swelling, tissue necrosis, gangrene, compartment syndrome, joint immobility, and contractures, amongst other physical deformities (Basit, 2023).

Frostbite injury is associated with morbidity, which is worse in the presence of hemorrhagic blisters, ongoing mottling, frank presence of frozen tissue, and no oedema (Basit, 2023).

The image below summarises the complications of cold burns, their mechanism, and management methods.

Managing Complications

Management of these long-term complications is challenging and include the below strategies (Zaramo, 2023).

- For chronic pain management, early use of chronic pain specialists and medications such as amitriptyline, gabapentin, duloxetine, and topical capsaicin are beneficial.

- Surgical and chemical sympathectomies, as well as Botox injections, have been proven to decrease pain and Raynaud-associated symptoms.

Complications of frostbite can include loss of nails, anhidrosis, and hyperhidrosis (Basit, 2023).

Conclusion

1. Overview: Frostbite is a freezing injury caused by prolonged cold exposure below 0°C, where heat loss exceeds perfusion. Management aims to salvage tissue and function.

2. Causes: Cold burns result from rapid or prolonged tissue cooling. Heat loss occurs via conduction, convection, radiation, and evaporation.

3. Types of Cold Injury: Cold injury types vary by freezing speed and ice crystal formation. Frostnip, chilblains, flash freeze, and frostbite are the main categories.

4. Pathophysiology: Cold exposure leads to ice crystal formation, cellular dehydration, and endothelial injury. Reperfusion causes inflammation, edema, and thrombosis.

5. Clinical Presentation: Frostbite is classified from first to fourth degree, ranging from superficial pallor and numbness to deep necrosis and mummification.

6. Diagnosis: Clinical diagnosis is supported by imaging (X-ray, bone scan, MRI) to assess tissue viability and plan surgical intervention.

7. Initial Management: Treat hypothermia, rapidly rewarm in 37–39°C water, control pain, use aloe vera, sterile dressings, and consider tPA or iloprost in deep frostbite.

8. Surgical Management: Surgical debridement or amputation is delayed until 4–6 weeks post-injury, when demarcation is complete. Early surgery is reserved for compartment syndrome.

9. Complications: Cold burns can lead to infection, neuropathy, chronic pain, autoamputation, joint stiffness, and cold intolerance. Management may be surgical or medical.

Further Reading

- Basit H, Wallen TJ, Dudley C. Frostbite. [Updated 2023 Jun 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536914/

- McIntosh SE, Freer L, Grissom CK, Rodway GW, Giesbrecht GG, McDevitt M, Imray CH, Johnson EL, Pandey P, Dow J, Hackett PH. Wilderness Medical Society Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Frostbite: 2024 Update. Wilderness Environ Med. 2024 Jun;35(2):183-197. doi: 10.1177/10806032231222359. Epub 2024 Apr 5. PMID: 38577729.

- Rintamäki H. Predisposing factors and prevention of frostbite. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2000 Apr;59(2):114-21. PMID: 10998828.

- Twomey JA, Peltier GL, Zera RT. An open-label study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of tissue plasminogen activator in treatment of severe frostbite. J Trauma. 2005 Dec;59(6):1350-4; discussion 1354-5. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000195517.50778.2e. PMID: 16394908.

- Roche-Nagle G, Murphy D, Collins A, Sheehan S. Frostbite: management options. Eur J Emerg Med. 2008 Jun;15(3):173-5. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e3282bf6ed0. PMID: 18460961.

- Handford C, Buxton P, Russell K, Imray CE, McIntosh SE, Freer L, Cochran A, Imray CH. Frostbite: a practical approach to hospital management. Extrem Physiol Med. 2014 Apr 22;3:7. doi: 10.1186/2046-7648-3-7. PMID: 24764516; PMCID: PMC3994495.

- Petrone P, Kuncir EJ, Asensio JA. Surgical management and strategies in the treatment of hypothermia and cold injury. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2003 Nov;21(4):1165-78. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8627(03)00074-9. PMID: 14708823.

- Chung 2024. Grabb and Smith's Plastic Surgery: 9th Edition September 2024 page 153

- Cauchy E, Chetaille E, Marchand V, Marsigny B. Retrospective study of 70 cases of severe frostbite lesions: a proposed new classification scheme. Wilderness Environ Med. 2001 Winter;12(4):248-55. doi: 10.1580/1080-6032(2001)012[0248:rsocos]2.0.co;2. PMID: 11769921.

- Lehmuskallio E. Emollients in the prevention of frostbite. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2000 Apr;59(2):122-30. PMID: 10998829.

- Dow J, Giesbrecht GG, Danzl DF, Brugger H, Sagalyn EB, Walpoth B, Auerbach PS, McIntosh SE, Némethy M, McDevitt M, Schoene RB, Rodway GW, Hackett PH, Zafren K, Bennett BL, Grissom CK. Wilderness Medical Society Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Out-of-Hospital Evaluation and Treatment of Accidental Hypothermia: 2019 Update. Wilderness Environ Med. 2019 Dec;30(4S):S47-S69. doi: 10.1016/j.wem.2019.10.002. Epub 2019 Nov 15. PMID: 31740369.

- Mohr WJ, Jenabzadeh K, Ahrenholz DH. Cold injury. Hand Clin. 2009 Nov;25(4):481-96. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2009.06.004. PMID: 19801122.

- Zaramo TZ, Green JK, Janis JE. Practical Review of the Current Management of Frostbite Injuries. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022 Oct 24;10(10):e4618. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000004618. PMID: 36299821; PMCID: PMC9592504.

- McCauley RL, Hing DN, Robson MC, Heggers JP. Frostbite injuries: a rational approach based on the pathophysiology. J Trauma. 1983 Feb;23(2):143-7. PMID: 6827634