Summary Card

Overview of Dynamic Reconstruction

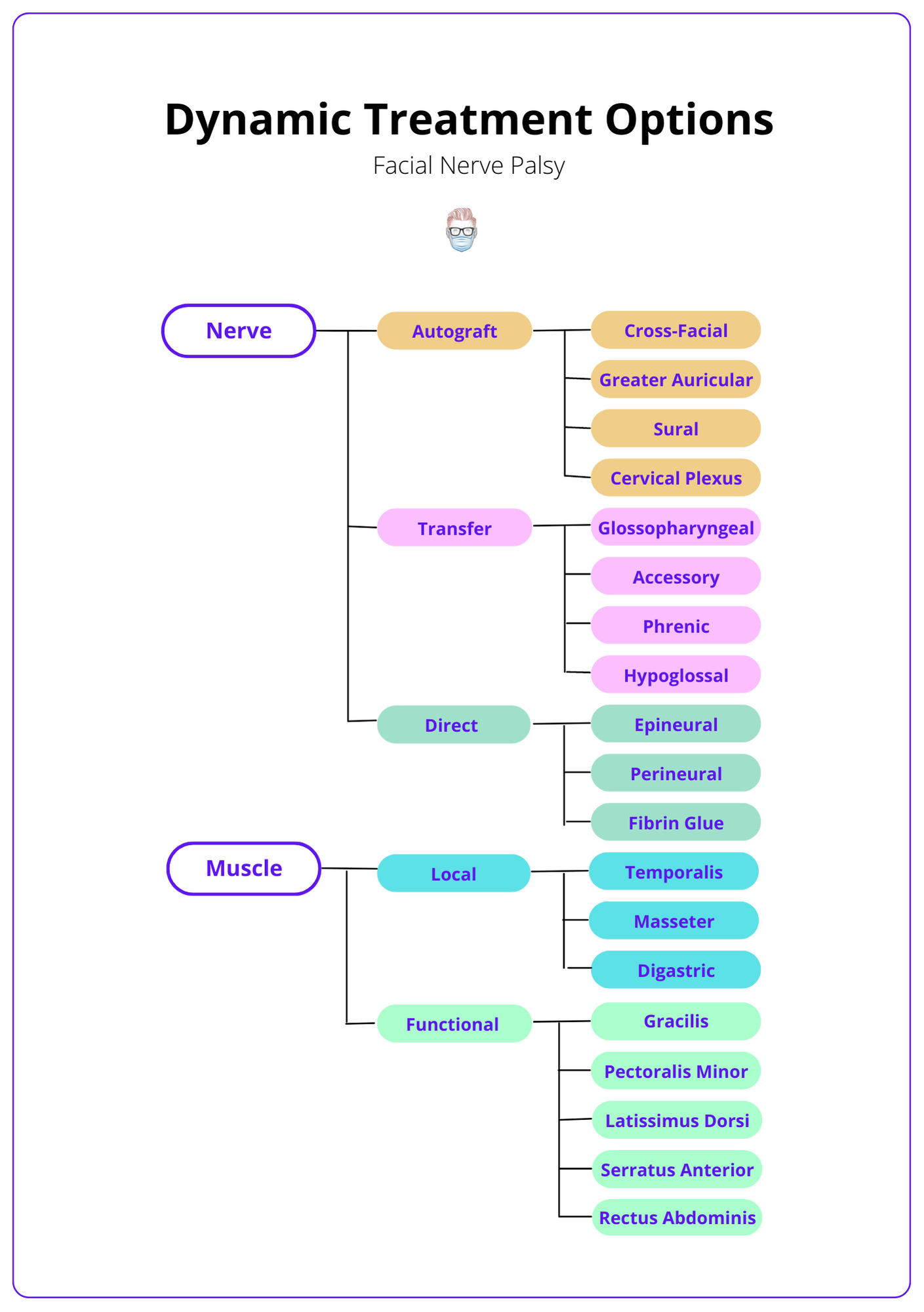

Dynamic reconstruction includes nerve grafts, nerve transfers, muscle transfers, muscle flaps or a combination.

Primary Facial Nerve Repair

Indicated in acute extra-cranial facial nerve injury with proximal and distal nerve stumps that can be repaired under minimal tension.

Ipsilateral Nerve Grafting

Indicated in acute extra-cranial nerve injuries with a wide neural gap that is not amenable to a tension-free direct repair.

Cross-Facial Nerve Graft

Indicated if distal branches present but no proximal stump ± muscle transfer if no viable facial muscle or babysitter procedure.

Nerve Transfers

Indicated if distal branches present but no proximal stump ± muscle transfer if there is no viable facial muscle ± CFNG.

Regional Muscle Transfer

Indicated when no viable muscles in long-standing palsy. The temporalis muscle is a commonly used option.

Free Muscle Transfer

Indicated if facial muscles will not provide useful function after motor reinnervation ± CFNG or babysitter procedure. Gracilis is the most commonly used.

Overview of Dynamic Reconstruction

Dynamic reconstruction options include nerve grafts, nerve transfers, muscle transfers, muscle flaps, or a combination of the above. This is guided by the patient, aetiology, timing, and location of facial nerve palsy.

Overview

Traditionally, there have been two ways to categorise operative techniques for facial nerve palsy:

- Non-operative: "conservative".

- Operative: static and dynamic reconstruction.

The aim of the treatment is:

- Symmetry at rest

- Dynamic, spontaneous movements

- Ocular, nasal and oral competence

- Corneal protection

- Reduce surgical morbidities

Reconstructive Strategy

The treatment options for facial nerve palsy can be simplified by looking at 3 key factors – aetiology, time, and location.

- Patient: what is their current status, and what is the aetiology of their facial nerve palsy. This will guide the expected clinical course and potential recovery.

- Time reflects the trophic status of the facial muscles. After 18 months, treatment options should include new muscle.

- Location reflects the viability of a proximal stump or distal branches. There is no proximal stump present in intra-cranial/intra-temporal palsy.

Based on these factors, a facial palsy patient will require nerve, muscle or a combination of both for successful dynamic reconstruction. This is illustrated in the diagram below.

Primary Facial Nerve Repair

Indication: Acute extra-cranial facial nerve injury with proximal and distal nerve stumps that can be repaired under minimal tension.

Primary facial nerve repair provides the best chance of nerve function recovery (Humphrey et al., 2008). It is the treatment of choice for acute extra-cranial facial nerve injuries (Humphrey et al., 2008) when there is a proximal and distal stump.

In terms of the surgical technique:

- Tension-free nerve coaptation with minimal anatomical displacement (Gordin et al., 2015).

- Patient must have viable facial muscle fibres and functional motor endplates.

- Within 72 hours, allow identification with a nerve stimulator.

- Epineural vs perineural is adequate (Gordin et al., 2015).

- Suture or fibrin glue – with no convincing superiority outcomes currently (Bozorg et al., 2004)

Ipsilateral Nerve Grafting

Indication: Acute extra-cranial nerve injuries with a wide neural gap that is not amenable to a tension-free direct repair.

Autologous ipsilateral nerve grafting is indicated in patients with facial palsy and a wide neural gap. Nerve grafting should go beyond the zone of injury.

Donor nerves for this technique include:

- Greater auricular nerve: 10 cm length, proximity to the operative field

- Sural nerve: 35cm length that can be neurolysed as segments (Chu & Byrne, 2008) and allows a two-team approach with minimal donor-site morbidity.

- Antebrachial cutaneous nerves: arm donor site morbidity (Myckatyn et al., 2003)

- Cervical Plexus: proximity to the operative field.

Advantages

- Donor nerves have a suitable length for reconstruction.

- Proximity to the operative field.

- Some donor nerves allow a two-team approach (sural nerve).

Disadvantages of this nerve grafting include:

- Numbness at donor site – sural nerve and lateral foot paraesthesia.

- Inadequate size match of donor and recipient nerves.

- Linked to synkinesis if performed in the intraosseous part of the facial nerve.

Cross-Facial Nerve Graft

Indication: Facial Palsy with no proximal stump but distal branches are present. This may be supplemented with a muscle transfer if there is no viable facial muscle in injuries in long-standing paralysis.

Overview

The VII-VII cross facial nerve graft (CFNG) was first described by Scaramella. It provides cross-innervation from the non-paralysed contralateral side to the paralysed ipsilateral side.

Technique

The CFNG can be performed as a one- or two-stage procedure. The growth of axons is assessed by an advancing Tinel's sign.

- Donor Graft: reverse sural nerve graft.

- Donor Nerve: a facial nerve branch that produces a smile without eye closure.

- Coaptation: distal nerve stumps or neurotisation directly into the muscle.

- Variations: followed by a free muscle transfer (after motor axonal growth) or combined with a "babysitter procedure" (partial hypoglossal to facial).

In a single-stage operation, both ends of the sural nerve graft are repaired. In a two-stage, repair the intact side. The graft is successful if a neuroma needs to be resected and an advancing positive Tinels sign.

Discussion

- Advantages: symmetrical spontaneous motion because of the fibres from the unaffected facial nerve acting as "pacemakers” for the affected side.

- Disadvantages: prolonged denervation period during the regenerative period can lead to irreversible muscle atrophy.

Nerve Transfers

Indication: Facial Palsy with no proximal stump and intact distal nerves. This may be supplemented with a muscle transfer if there is no viable facial muscle in injuries.

Overview

Nerve transfers are suitable for patients with an intact distal nerve but no proximal stump. In rarer cases, it can also be used in Mobius Syndrome, where a cross-facial nerve graft is contraindicated or as a babysitter procedure, as described above.

Technique

The donor nerves include nerve to masseter, glossopharyngeal, accessory, phenic and hypoglossal.

In a hypoglossal (XII) to the facial nerve (VII) nerve transfer:

- The hypoglossal is near the extratemporal facial nerve.

- XII is divided distally and reflected up to VII.

- Can consider a "jump graft": end-to-side coaptation of a nerve graft to XII and the other end of the graft is sutured to the distal stumps of VII (preserves ipsilateral tongue function).

In a “babysitter procedure” described by Terzis:

- A cranial nerve transfer acting as a babysitter to the musculature by providing a faster route to re-innervation.

- It preserves the musculature and possibly the denervated stump while the axons grow across the cross-face nerve graft.

- For example: the motor nerve to masseter.

Discussion

- Advantages: provide good muscle tone, powerful excursion.

- Disadvantage: sacrifice a donor cranial nerve and can produce synkinesis.

Regional Muscle Transfer

Indication: When there is no viable musculature.

When there is no viable musculature, then muscle should be imported. This occurs after long-standing atrophy. Local muscle flaps have been described to dynamize the face by utilising the functional trigeminal nerve on the paralysed side.

Temporalis Muscle Transfer

- Origin: As described by Gilles, Labbé, Hault and many other variations.

- Anatomy: fan-shaped muscle from temporal fossa to coronoid process supplied by temporal artery & innervated by the trigeminal nerve.

- Procedure: the strip of muscle is folded over the zygomatic arch and inserted into the eye or oral commissure ± detached from coronoid insertion.

Masseter Muscle Transfer

- Indication: restore motion to the lower part of the face.

- Technique: released from the mandible and attached to orbicularis.

Digastric Muscle Transfer:

- Indication: restore lower lip depressor function in mandibular branch nerve injuries.

- Technique: anterior digastric tendon is inserted into the orbicularis at the lower vermillion, central to the commisure.

Disadvantages:

- Muscle transpositions are usually unable to recreate a spontaneous dynamic smile as activation of the muscle requires a specific manoeuvre (such as clenching the teeth).

- Most donor muscles are innervated by the trigeminal nerve, so they don't produce true mimetic function.

Free Muscle Transfer

Indication: Facial muscles will not provide useful function after motor reinnervation.

Facial re-animation with free muscle transfer is indicated when facial muscles will not provide useful function after reinnervation. It requires both neural control and muscle recruitment.

It can be a one-stage operation if a masseteric nerve transfer is possible. It is typically a two-stage operation requiring a CFNG followed by a microneurovascular muscle transfer.

General Principles

- Match the size of donor and recipient nerves.

- Leave the donor short to minimize re-innervation time.

- Allow for 50% loss of power following transfer.

- Match size and shape of donor's muscle to available pocket.

Donor Muscle Options:

- Gracilis: most commonly used

- Latissimus Dorsi

- Pectoralis Minor

- Extensor digitorum brevis

Conclusion

1. Dynamic Facial Palsy Reconstruction: You have gained a thorough understanding of dynamic reconstruction options for facial palsy, including nerve grafts, nerve transfers, muscle transfers, and muscle flaps. This knowledge will help in identifying the appropriate intervention based on patient-specific factors such as the aetiology, timing, and location of the facial nerve palsy.

2. Exploring Specific Treatments: You've explored detailed treatment modalities for various scenarios of facial nerve injury. These include primary facial nerve repair for acute injuries with available nerve stumps, ipsilateral nerve grafting for wide neural gaps, and cross-facial nerve grafting for cases with distal branches but no proximal stump.

3. Learning Surgical Techniques: The article has introduced you to advanced surgical techniques and considerations, such as the use of regional muscle and free muscle transfers to restore facial function, especially in long-standing cases where muscle reinnervation is unlikely.

4. Appreciating Complex Decision-Making: You've learned how the choice of surgical intervention is influenced by multiple factors, including the duration of the palsy, the presence or absence of nerve stumps, and the viability of facial musculature, which requires a nuanced understanding for effective treatment planning.

Further Reading

- Humphrey C, Kriet J. Nerve repair and cable grafting for facial paralysis. Facial Plast Surg. 2008;24(2):170-176. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1075832

- Gordin E, Lee T, Ducic Y, Arnaoutakis D. Facial nerve trauma: evaluation and considerations in management. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2015;8(1):1-13. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1372522

- Bozorg Grayeli A, Mosnier I, Julien N, Garem H, Bouccara D, Sterkers O. Long-term functional outcome in facial nerve graft by fibrin glue in the temporal bone and cerebellopontine angle. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. September 2004:404-407. doi:10.1007/s00405-004-0829-6

- Millesi H. The nerve gap. Theory and clinical practice. Hand Clin. 1986;2(4):651-663.

- Chu E, Byrne P. Treatment considerations in facial paralysis. Facial Plast Surg. 2008;24(2):164-169. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1075831

- Myckatyn T, Mackinnon S. The surgical management of facial nerve injury. Clin Plast Surg. 2003;30(2):307-318. doi:10.1016/s0094-1298(02)00102-5

- Darrouzet V, Duclos J, Liguoro D, Truilhe Y, De B, Bebear J. Management of facial paralysis resulting from temporal bone fractures: Our experience in 115 cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125(1):77-84. doi:10.1067/mhn.2001.116182

- Liu Y, Han J, Zhou X, et al. Surgical management of facial paralysis resulting from temporal bone fractures. Acta Otolaryngol. 2014;134(6):656-660. doi:10.3109/00016489.2014.892214

- Nash J, Friedland D, Boorsma K, Rhee J. Management and outcomes of facial paralysis from intratemporal blunt trauma: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2010;120 Suppl 4:S214. doi:10.1002/lary.21681