Author: Joanna Low, London, 4th Year Medical Student

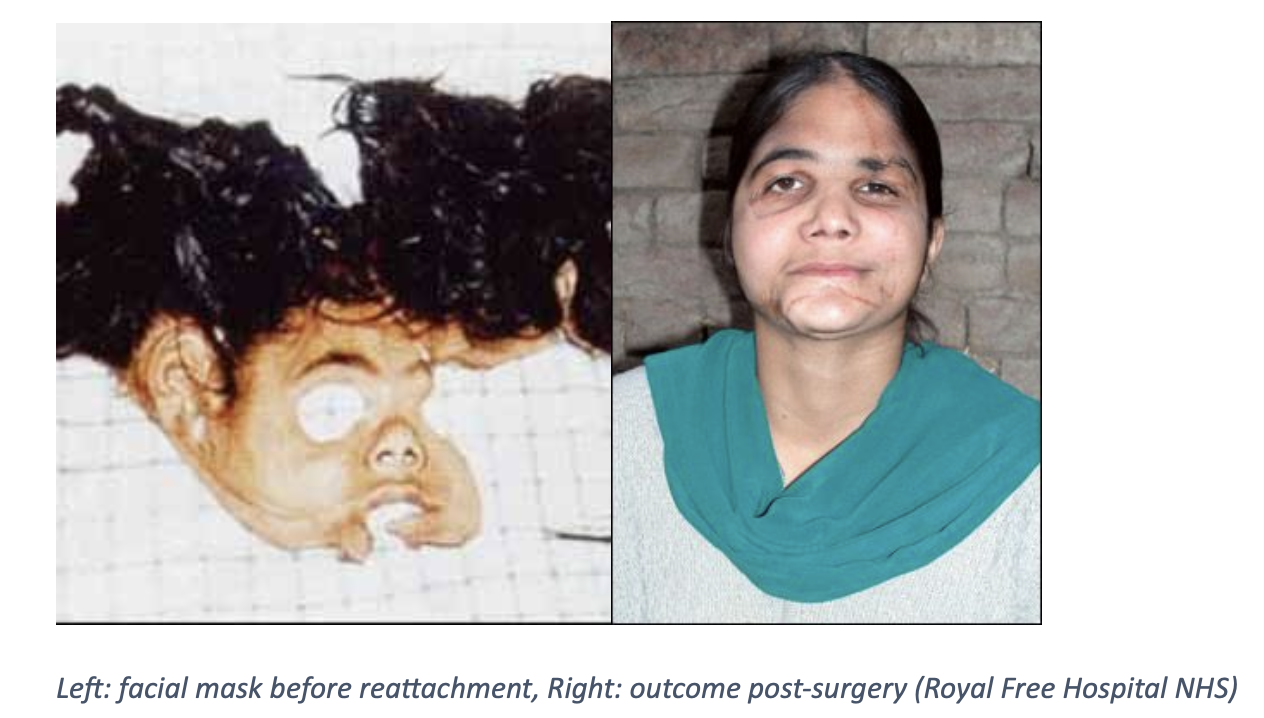

Facial transplantation is an exciting and new development in plastic surgery. The first facial allograft transplantation (FAT) was performed in France in 2005, ushering in a new paradigm of reconstructive microsurgery. Since then, 35 procedures have been performed worldwide with a patient survival rate of 86%. Before FAT, the only option for such patients was conventional reconstruction with autologous tissues such as skin, muscles and bones.

Facial transplantation is viewed as a quality of life improving rather than life-saving intervention. It is used to repair complex craniofacial defects in the context of advanced disease, trauma or congenital malformations, where traditional autologous reconstruction would be suboptimal. Due to the potential of post-transplant complications, the risks and benefits of performing FAT must be weighed carefully.

Patient Selection

The American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) and the American Society of Reconstructive Microsurgery (ASRM) have recommended the following indication criteria for FAT:

- Severe facial disfigurement (loss of more than 25% of the total face and/or central facial units) after unsuccessful attempts at conventional autologous reconstruction

- Ballistic trauma

- Severe burn injury

Currently, up to two-thirds of current FAT recipients are ballistic trauma and burn victims, as these injuries often include severe skin damage, tissue loss and disfigurement. Other indications include gunshot wounds, neurofibromatosis 1, animal attacks and cancer defects.

The exclusion criteria set by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital team includes:

- History of psychiatric illness on medications

- Patients previously non-compliant with care and follow up

- Previous liver, lung or heart transplantation

Surgery

FAT is an extensive surgery lasting anywhere from 8 to 36 hours, followed by a long hospital stay. The surgical stages of FAT include graft procurement, preservation and transplantation using the microsurgery technique of ‘free tissue transfer’. The facial artery is often used as the main pedicle for facial allografts, as it is the main arterial supply to the facial skin envelop. Nerve repair is essential for motor and sensory function of the face. Craniofacial alignment, dental occlusion and orthognathic planning are also necessary in determining facial width, position, and speech and airway function.

Outcomes

Motor recovery post-FAT can be detected 6-8 months after the procedure. This includes functional outcomes such as breathing, eating, speaking, and facial sensations. Several studies have reported an overall improved functionality in these areas compared to pre-transplantation impairment. Speech and swallow therapy has also been shown to improve recovery.

Sensation in the allograft returns as early as 3 months post-FAT, with satisfactory levels reported around 8-12 months.

Quality of life outcomes post-transplant vary widely, and is largely affected by the impact of the surgery on the patient’s psychological status. Several challenges reported by these patients post-surgery include drug or alcohol abuse, behavioural changes, social disintegration, family issues, depression, and suicidal attempts. In many Asian countries, patients and families also report a feeling of guilt about facial harvesting from a donor. In view of this, a follow-up psychological consultation is often done.

Complications

The surgical complications of FAT include blood loss, wound healing difficulties, graft misalignment, bone non-union, eyelid asymmetry and ptosis, etropion, and functional impairment like obstruction of nasal passages and salivary glands, and necrosis of the hard palate. Occasionally, these require secondary revisions for aesthetic and functional purposes.

Opportunistic cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is more commonly seen in solid organ transplantation and has been reported in more than one-third of FAT recipients, despite targeted antibiotic prophylaxis. This may lead to allograft dysfunction and increasing mortality and morbidity risks.

Patients are started on long-term immunosuppression post-transplantation, which carries many complications in itself. These include metabolic complications, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia, chronic kidney damage, and malignancies like EBV- and HIV-associated lymphoma, cervical dysplasia, and lung cancer.

Acute rejection of the allograft occurs frequently in FAT, occurring in up to 80% of patients within the first year. Chronic rejection has also been reported in FAT, although less frequently than predicted.

Ethics

There is much ongoing debate about the ethics involved in facial transplantation and changing identity. The main concerns raised are:

- Ability to achieve informed consent for a new and uncertain procedure

- Psychological aspects of facial transplantation and altered appearance

- Impact of acute and chronic rejection of a face transplant and need for lifelong immunosuppression drugs

Despite this, majority of studies support the use of FAT for the reconstruction and restoration of function and appearance of severely facially disfigured individuals. This is due to the significant improvements in short-term outcomes, which has seen successful reintegration of patients into the outside world and even the workplace.

References

- Pomahac, B., Aflaki, P., Chandraker, A. and Pribaz, J., 2008. Facial Transplantation and Immunosuppressed Patients: A New Frontier in Reconstructive Surgery. Transplantation, 85(12), pp.1693-1697.

- Pomahac, B., Nowinski, D., Diaz-Siso, J., Bueno, E., Talbot, S., Sinha, I., Westvik, T., Vyas, R. and Singhal, D., 2011. Face Transplantation. Current Problems in Surgery, 48(5), pp.293-357.

- Tasigiorgos, S., Kollar, B., Krezdorn, N., Bueno, E., Tullius, S. and Pomahac, B., 2018. Face transplantation-current status and future developments. Transplant International, 31(7), pp.677-688.

- Eun, S., 2015. Facial Transplantation Surgery Introduction. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 30(6), p.669.

- Royalfree.nhs.uk. 2021. Responding to face transplant ethics. [online] Available at: <https://www.royalfree.nhs.uk/services/services-a-z/plastic-surgery/facial-reconstruction-and-face-transplants/facial-reconstruction-and-face-transplants/> [Accessed 6 February 2021].