In this Article

Anatomy of Zygomaticomaxillary Complex

The Zygomaticomaxillary complex (ZMC) is a 3-dimensional structure which defines midface width and projection, as well as providing shape to the orbit.

Bone

Zygomaticomaxillary complex (ZMC) fractures refer to the disruption of 4 buttresses in the malar eminence. There are four points of fixation of the zygoma

- Zygomaticomaxillary articulation and inferior orbital rim.

- Zygomaticosphenoid articulation in the lateral orbital wall.

- Zygomaticofrontal articulation and the lateral orbital rim.

- Zygomatic arch.

This fracture is sometimes referred to as a “tripod fracture”, but this is a misnomer. The zygoma has articulations with frontal, maxillary, and temporal bones, as well as greater wing of the sphenoid. It should be called a 'tetrapod'19.20.

Soft Tissue

The Zygoma serves as a muscular insertion point of the:

- Masseter: elevates and protudes the mandible.

- Temporalis: elevates and retracts the mandible.

- Zygomaticus Major and Minor Muscles: upward and lateral movement.

By understanding these muscular forces on the mandible, it makes it easier to understand the clinical findings of the fracture and surgical techniques.

It is also closely linked to the infra-orbital nerve and can be injured in ZMC fractures.

Assessment of ZMC Fractures

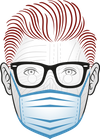

All trauma patients should be evaluated as per ATLS guidlines. Specifically focusing on the ZMC fracture, the signs and symptoms can be remembered by the following mnemonic: 6P's of ZMC Fractures (a P'Fella original)

- Periorbital swelling

- Pain in extremes of gaze

- Perception: Diplopia and lateral subconjunctival blood

- Paraesthesia in V2 distribution

- Projection: lack of malar prominence

- Protusion: Enophthalmos or exophthalmos

History

A large number of these patients receive an injury in low and high-velocity trauma. The mechanism of injury is one of the key parts to the history. Patients may also complain of:

- Numbness in check due to infra-orbital nerve damage (often cannot be corrected at surgery1,2)

- Trismus - ZMC is close to the coronoid process of mandible and TMJ.

Examination

In a trauma situation, it can be difficult to visualise all aspects of the injury.

On General Inspection, important points to note are:

- Facial width and projection.

- Echymosis.

- Soft Tissue Lacerations.

- Step-offs and lack of malar prominence.

In terms of ocular findings, important findings inlcude:

- Blood in lateral sclera: sign of lateral orbital wall fracture.

- Orbital volume changes: this is most commonly enopthalmos once oedema has resolved. If lateral blow-out fractures occur, then exophthalmos may occur.

- Extraocular muscular entrapment: disconjugate gaze, photophobia, and nausea confirmed by a forced duction test4.

Formal assessment by Ophthalmology should be considered to assess for:

- Orbital apex or superior orbital fissure syndrome

- Retrobulbar haematoma5-7

- Traumatic retinal detachement8

Important Point:

Always Assess the C-Spine - concomitant injuries ~10% with facial fractures9

Investigations

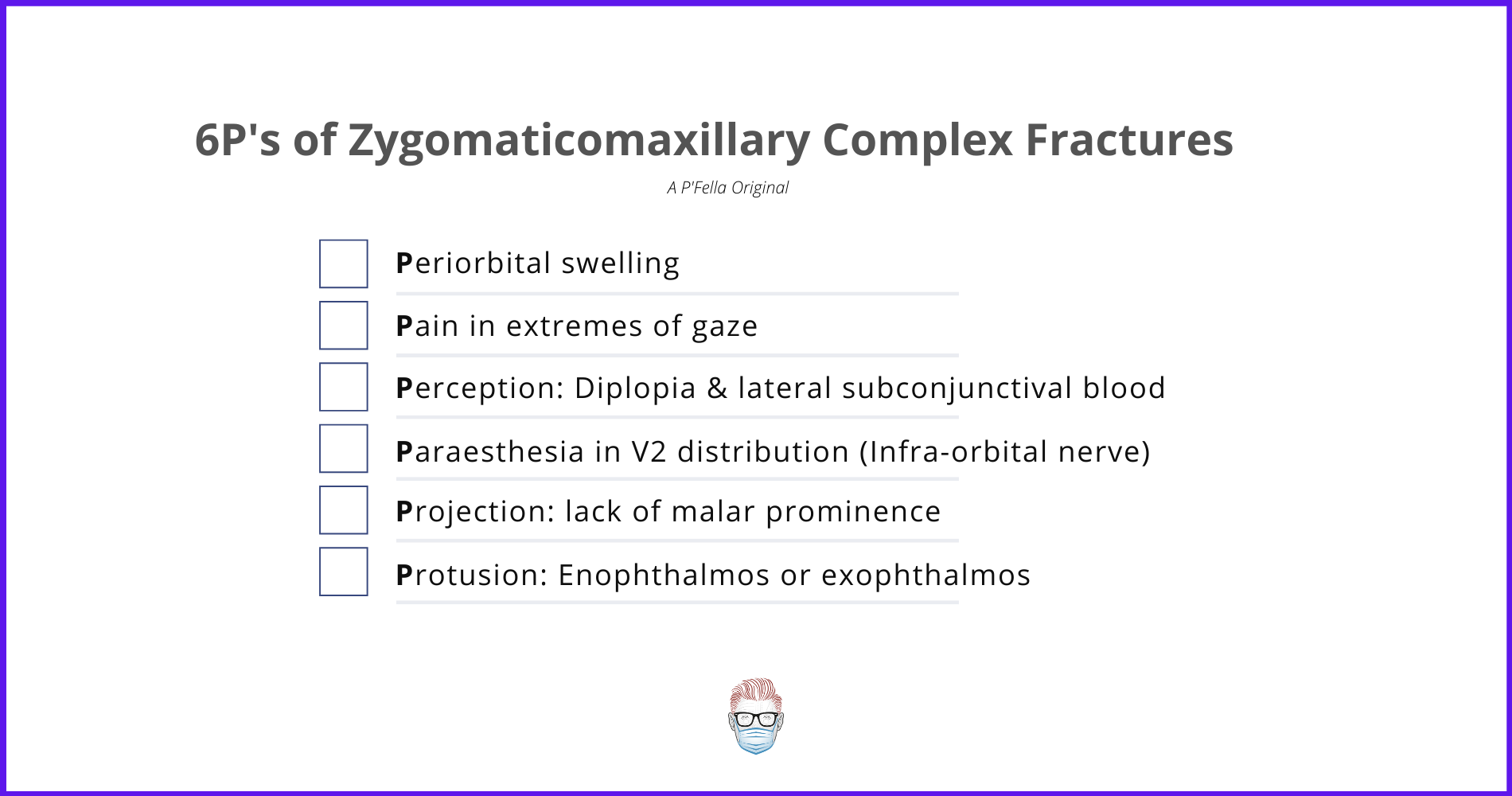

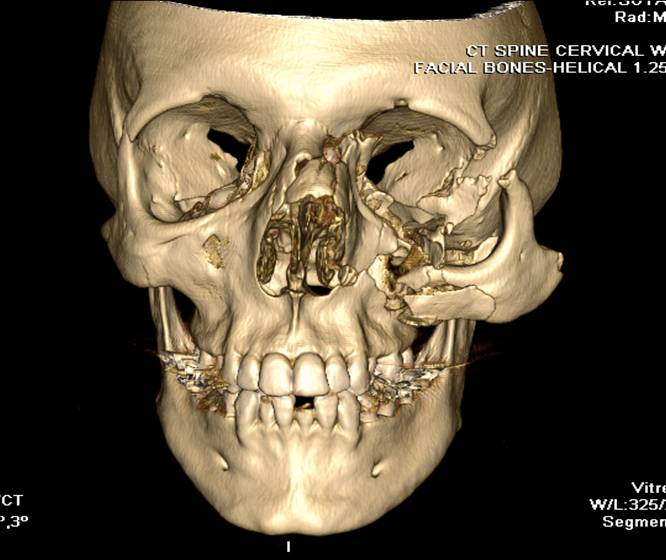

A fine-cut CT with coronal, sagittal and axial views allowing for 3D reconstrucitons is considered the gold-standard.

These images are provided by Dr David Cuete, Radiopaedia.org (case rID: 33606)

A plain X-Ray is commonly performed as routine, however it is not the gold-standard. Ultrasound has been documented10,11.

In 1992, Zingg et al21 classified fracture patterns into 4 categories:

- Type A: Incomplete zygomatic fracture

- Type B: Complete monofragment zygomatic fracture (tetrapodfiacture).

- Type C: Multifragment zygomatic fracture.

This classificaton system can help guide management.

Management of ZMC Fracture

The treatment of zygomaticomaxillary complex fractures should be centred on two questions. Does this ZMC fracture need surgery? If so, when should it be operated on? The decision should have both functional and aesthetic considerations13-16.

General Principles

The goal of treatment is to determine the need for closed or open reduction, three-dimensional alignment and fixation, and the management of concomitant infraorbital rim and orbital floor fractures18. The type of treatment is depedent on fracture pattern and surgical preferences.

Timing of Surgery

Emergency surgery is indicated in patients with major sequelae of the ZMC fracture. This includes, but not limited to:

- Extra-ocular muscular entrapment

- Retrobulbar haematoma

- Apex Syndrome

Delayed Surgery17 is indicated in the majority of patients to let the oedema settle. The exact timing is patient and surgeon-dependent. General suggestions are:

- Adults: 1-2 weeks

- Children: 1 week (earlier bone remodelling)

If the surgery is too delayed (~>4 weeks), this can result in more complex surgical interventions, such as done grafting.

Surgical Techniques

Surgical techniques are dependent on the patient, type of fracture and surgeon. In general, the least amount of rigid fixation needed to obtain a stable bony union is applied12.

An in-depth review of surgical techniques is outside the scope of this article. A biref overview includes:

- Fracture Fixation via plates and screws.

- Material of fixation can be resorbable vs titanium.

- Soft Tissue closure to provide adequate soft-tissue coverage, aesthetic outcomes and ocular competence.

References

- Kurita M, Okazaki M, Ozaki M, et al. Patient satisfaction after open reduction and internal fixation of zygomatic bone frac- tures. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:45–49.

- Mottini M, Wolf R, Soong PL, Lieger O, Nakahara K, Schaller B. The role of postoperative antibiotics in facial fractures: Comparing the efficacy of a 1-day versus a prolonged regi- men. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:720–724.

- Hazani R, Yaremchuk MJ. Correction of posttraumatic enophthalmos. Arch Plast Surg. 2012;39:11–17.

- Jordan DR, Allen LH, White J, Harvey J, Pashby R, Esmaeli B. Intervention within days for some orbital floor frac- tures: The white-eyed blowout. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;14:379–390.

- McClenaghan FC, Ezra DG, Holmes SB. Mechanisms and management of vision loss following orbital and facial trauma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011;22:426–431.

- Popat H, Doyle PT, Davies SJ. Blindness following retrobul- bar haemorrhage: It can be prevented. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;45:163–164

- McInnes G, Howes DW. Lateral canthotomy and cantholysis: A simple, vision-saving procedure. CJEM 2002;4:49–52.

- Bater MC, Ramchandani PL, Brennan PA. Post-traumatic eye observations. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;43:410–416.

- Mulligan RP, Mahabir RC. The prevalence of cervical spine injury, head injury, or both with isolated and mul- tiple craniomaxillofacial fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg.2010;126:1647–1651.

- Adeyemo WL, Akadiri OA. A systematic review of the diag- nostic role of ultrasonography in maxillofacial fractures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;40:655–661.

- Ogunmuyiwa SA, Fatusi OA, Ugboko VI, Ayoola OO, Maaji SM. The validity of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of zygo- maticomaxillary complex fractures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41:500–505

- Birgfeld CB, Mundinger GS, Gruss JS. Evidence-Based Medicine: Evaluation and Treatment of Zygoma Fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017 Jan;139(1):168e-180e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002852. PMID: 28027253.

- Hollier LH Jr, Sharabi SE, Koshy JC, Stal S. Facial trauma: General principles of management. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:1051–1053.

- Burnstine MA. Clinical recommendations for repair of orbital facial fractures. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2003;14:236–240.

- Kelley P, Hopper R, Gruss J. Evaluation and treatment of zygomatic fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(Suppl 2):5S–15S.

- Ellstrom CL, Evans GR. Evidence-based medicine: Zygoma fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:1649–1657.

- Carr RM, Mathog RH. Early and delayed repair of orbitozygo-matic complex fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55:253–258.

- Zingg M, Laedrach K, Chen J, Chowdhury K, Vuillemin T, Sutter F, Raveh J. Classification and treatment of zygomatic fractures: a review of 1,025 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992 Aug;50(8):778-90. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(92)90266-3. PMID: 1634968.

- Eisele DW, Duckert LG: Single-point stabilization of zygomatic fractures with the minicompression plate. Arch Gtolaryngol Head Neck Surg 113:267, 1987

- Karlan MS, Cassisi NJ: Fractures of the zygoma. Arch Gtolaryngol Head Neck Surg 105:320, 1979